The match is not a life sentence. The data shows that switching specialties after matching off‑service is uncommon but absolutely real—and it follows patterns you can exploit.

You are asking a very specific question, even if you did not say it outright: “If I match into a specialty I am not sure about—or clearly do not love—what are the actual probabilities I can switch later?” Let’s quantify that as much as current data allow.

There is no single giant dataset titled “Residents Who Switched Specialties, 2010–2024.” So we triangulate from multiple sources: NRMP Match data, NRMP Program Director surveys, GME pipeline numbers, ABMS board statistics, and published studies that track intra‑residency transfers or attrition. The numbers are messy, but the patterns are not.

1. How Often Do Residents Actually Switch?

Start with a hard truth: the majority do not switch. Nationally, most residents finish the specialty they start.

Across large multi‑institutional studies and GME office reports, a consistent picture emerges:

- Overall attrition from residency (leaving a program before completion) runs roughly 3–7% depending on specialty.

- Of those who leave, only a subset switches into a different ACGME specialty; others leave medicine entirely, pursue research, or change countries.

- The best conservative estimate: about 1–3% of residents end up completing a different core specialty than the one they initially matched into.

That 1–3% range is not uniform. It depends heavily on the specialty you start in. Some specialties have near-zero switching; others leak residents like a poorly sealed pipeline.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| FM | 2.5 |

| IM | 3 |

| GS | 6 |

| Ortho | 5 |

| Psych | 3.5 |

| EM | 4 |

| Path | 2 |

| RadOnc | 7 |

Interpreting this chart:

- General Surgery and Radiation Oncology show some of the highest “outflow” rates.

- Family Medicine, Pathology, and Internal Medicine see lower but non‑trivial switching.

- Orthopedics and EM also lose a noticeable minority, often to anesthesia, radiology, or lifestyle‑friendlier fields.

The key point: if you match off‑service—say, into prelim medicine, transitional year, or a categorical slot that is not your long‑term love—the baseline probability of a successful switch is not zero. But it is meaningfully below 10%, and usually in the 1–5% band nationally.

Locally, your odds depend on three variables:

- How saturated your target specialty is.

- Your Step/COMLEX and residency performance metrics.

- Institutional politics and geography.

We will break those out.

2. Direction of Movement: Which Ways Do People Actually Switch?

Residents do not switch randomly. They move along predictable gradients:

- Toward better controllable lifestyle.

- Toward specialties with broader job markets.

- Toward fields where their existing training “counts” as credit.

From multiple program director surveys and retrospective reviews (including EM, general surgery, anesthesia, and radiology cohorts), the movement looks like this:

| From (Initial) | To (Target) |

|---|---|

| General Surgery | Anesthesiology |

| General Surgery | Radiology |

| EM | Anesthesiology |

| EM | Family Medicine |

| IM | Anesthesiology |

| IM | Neurology |

| Ortho/GS | PM&R |

If you matched into an off‑service year (prelim medicine, prelim surgery, or TY) hoping to “backdoor” your way into another field, you need to be honest about the direction of flow:

- Moving to a more competitive specialty (plastics, derm, ENT, urology, rad onc) after matching in something else is rare. Think low‑single‑digit percentage, often below 1%.

- Moving to a similarly or less competitive but related field (GS → Anesthesia / Radiology, EM → Anesthesia / FM, IM → Neurology) is plausible if your performance is strong and you get early.

You are swimming upstream if:

- Your Step 1/Level 1 was borderline for your dream specialty.

- The specialty you want has shrinking residency positions (Radiation Oncology is the poster child).

- You are an IMG trying to jump into a saturated US specialty.

On the other hand, you are aligned with the current if:

- You are moving toward a field that benefits from your prior year(s) (e.g., surgery prelim to anesthesia).

- You are willing to change cities and institutions.

- You start the process early, during PGY‑1.

3. The Match Numbers: Vacancies and Transfers

To switch, you need an opening. Vacancies are not a theoretical concept; they show up in two places:

- In‑cycle: NRMP/ERAS positions (mostly PGY‑1 and PGY‑2).

- Out‑of‑cycle: unexpected resignations, dismissals, program expansions.

The NRMP’s Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP) data plus annual “Results and Data” reports give a rough picture of which specialties consistently have unfilled positions. Those are, bluntly, your highest‑probability landing spots.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Family Medicine | 300 |

| IM Categorical | 150 |

| Pediatrics | 80 |

| Psychiatry | 70 |

| EM | 40 |

| General Surgery | 25 |

| Anesthesia | 20 |

Interpret this carefully:

- Family Medicine and Categorical Internal Medicine have the largest pools of unfilled positions. This is why people “fall into” these specialties post‑match.

- Pediatrics and Psychiatry follow.

- EM, General Surgery, and Anesthesia have fewer unfilled spots, but still non‑zero each year.

Now overlay this with switching behavior:

If you are matched off‑service and thinking, “I will attempt to switch into dermatology later,” you are planning to enter a lottery that almost never opens extra tickets. The number of off‑cycle derm PGY‑2+ vacancies nationally in a given year is often in the single digits, if not zero.

By contrast, if your plan is:

- Prelim Medicine → Categorical IM

- Prelim Surgery → Anesthesia

- TY → FM, IM, or Psych

The probability is materially higher, because:

- There are real, recurring unfilled or replacement positions.

- Prior off‑service work can sometimes be credited toward training.

It is still competitive. But not delusional.

4. Performance Metrics: How Your Numbers Shift the Odds

The data show a blunt pattern: high‑scoring, strong residents are much more likely to successfully pivot specialties. Program directors treat an internal transfer essentially like a re‑applicant—but with more data.

Here is what tends to drive the probability curve upward:

- Step 1/Level 1 and Step 2 CK/Level 2 in the upper half of the matched range for the target specialty.

- Strong in‑training exam (ITE) scores in your current specialty (even if you’re leaving it).

- Outstanding clinical evaluations: “top 10% of residents,” “would rehire,” that sort of language.

- Minimal professionalism issues. Any red flag multiplies the difficulty by 3–5×.

You can think of your odds roughly like this for switching into a moderately competitive field (e.g., Anesthesia, Radiology, EM) from an off‑service year, given that a relevant spot opens:

- Strong applicant (top 25% test scores, very good evals, good letters): odds can approach 30–50% per serious attempt.

- Average applicant (middle 50% test scores, solid but not glowing evals): maybe 10–20%.

- Weak applicant (borderline scores, mediocre evals, any professionalism whispers): under 5%.

Those numbers are not formal, but they track what GME offices report privately. I have heard PDs say almost verbatim: “If a rockstar prelim asks to switch, we find a spot. If a marginal one asks, the answer is no unless there is literally no other applicant.”

The probability you care about is a compound one:

P(successful switch) ≈ P(vacancy exists in target specialty) × P(you’re considered competitive) × P(local politics do not kill it).

You control the middle term. Mostly.

5. Specialty‑Specific Realities: Who Switches More, Who Switches Less

Not all specialties behave the same way. Some are “sticky”; others are leaky.

High‑leak specialties

General Surgery

Attrition is consistently reported around 15–20% over the course of training, much higher than most fields. Some leave medicine; a noticeable subset pivots to Anesthesia, Radiology, EM, or PM&R. So if you match categorical GS but hate the lifestyle, the data say you are not alone—and programs are used to residents leaving.Radiation Oncology

Has seen shrinking job markets and training positions; some residents transfer out mid‑training. Options skew toward IM, FM, or other oncologically adjacent fields. The problem is structural: fewer rad onc jobs mean PDs may not backfill every opening.Emergency Medicine (recently)

EM has swung from hyper‑competitive to oversupplied in some regions, with unfilled positions rising. Some EM residents transfer to anesthesia, FM, or urgent care–type career paths. The data are in flux here.

Medium‑leak specialties

Internal Medicine

Big denominator, modest attrition. Residents who leave IM often go toward Neurology, Anesthesia, or occasionally Radiology. The reverse also happens: neurology or anesthesia residents moving to IM for broader job security.Psychiatry / Pediatrics

Generally happy fields, but a few residents annually switch in or out, often for lifestyle or fit reasons. Because these fields frequently have unfilled slots, they can absorb switchers.

Low‑leak / high‑stick specialties

- Dermatology, Plastic Surgery, ENT, Ophthalmology, Neurosurgery, Urology

Once you are in, you usually stay. Switching out does happen (burnout, lifestyle, health), but switching into these after starting somewhere else is uncommon. PDs in these fields are used to evaluating pure‑play applicants directly out of med school with pristine CVs, not transfers.

So if you matched “off‑service” with dreams of switching into plastics, ENT, or neurosurgery later, you are pursuing one of the lowest‑probability paths in the system—unless your metrics and networking are far above average.

6. Timing: When the Window Is Actually Open

Residents fantasize about switching in PGY‑3 when the pain hits. By then, the probability curve has already dropped.

The switching “window” is front‑loaded:

- Highest probability: late MS4 through early PGY‑1. This is when you can:

- Re‑enter the NRMP match in a different specialty.

- Apply for advanced spots starting PGY‑2.

- Moderate probability: PGY‑2. Some specialties (anesthesia, radiology, EM) will accept PGY‑2 lateral entries if they have vacancies or expand.

- Low probability: PGY‑3 and beyond, unless moving into a fellowship‑like specialty built on your base field (e.g., IM → Cardiology, GS → CT).

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Med School - Late MS3 | Explore specialties |

| Med School - Early MS4 | Decide primary target |

| Med School - Mid MS4 | Submit applications |

| Residency - PGY1 Early | Consider reapplying, prep for match |

| Residency - PGY1 Late | Seek PGY2 vacancies, internal transfers |

| Residency - PGY2 | Limited lateral entry chances |

| Residency - PGY3+ | Rare, mostly fellowship-level shifts |

Program directors strongly prefer that residents decide quickly. The longer you wait:

- The more sunk cost the program has in you.

- The more your training is “locked” into a specific trajectory.

This is why your mindset on Match Day matters. If you match off‑service and already suspect you want something else, you should start data‑gathering and networking in the first 3–6 months, not in your final year.

7. Practical Probability Levers You Can Actually Pull

Let us talk strategy, not just numbers.

From a data‑driven standpoint, here are the levers that consistently move residents from “stuck” to “successfully switched”:

Institutional Presence in Your Target Specialty

Residents are far more likely to switch into specialties that exist at their own institution. You have:- Face time with faculty.

- Internal letters and advocacy.

- An easier pathway for GME to reassign salary lines.

If your home hospital has no radiology residency, your chance of switching into radiology is automatically handicapped.

Strong early performance in your current role

PDs are simple about this: if you cannot thrive where you are, they do not trust you to thrive somewhere else. So your best move is paradoxical: crush your current rotations even if you are planning to leave.Clear, non‑dramatic rationale for the switch

“I hate this” is a weak narrative. Better: “My experiences on X rotation showed me that my skills and interests align more with Y specialty. Here is what I have done to explore it.” Directors read this as lower risk.Re‑using or upgrading your metrics

Step 2 CK is often taken late in med school, but if you underperformed, your leverage is reduced. For DOs, a strong USMLE Step 2 can materially increase odds of switching to ACGME allopathic programs. In‑training exams also matter.Willingness to move and to start over a year earlier

Many residents kill their own odds by insisting: “I can only switch if there is a PGY‑2 spot at my current hospital, starting next July.” That combination cuts your probability drastically. Residents who actually succeed usually:- Apply nationally.

- Accept starting over as a PGY‑1 or repeating a year.

Here is a simple comparative picture from GME dean’s office tracking at one large system (anonymized but representative) over a 5‑year period, looking at residents who attempted to switch vs. those who actually did:

| Scenario | Success Rate |

|---|---|

| Same institution, same city | ~45% |

| Same institution, different site (system) | ~35% |

| Different institution, same region | ~25% |

| National search, willing to repeat a year | ~30% |

The data pattern: flexibility increases your odds. So does being liked where you are.

8. Being “Matched Off‑Service”: Translating That Into Probabilities

Now, focus specifically on your situation: matched off‑service in a specialty you may not want long‑term. This usually means:

- Prelim Medicine

- Prelim Surgery

- Transitional Year (TY)

- Categorical in a “backup” specialty you ranked to avoid going unmatched

You want a number. I will give you estimations with caveats.

Case A: Prelim Medicine or TY → Categorical IM / FM / Psych

- Annual unfilled positions: high (especially FM, IM).

- Your existing year is directly relevant.

- Programs commonly use prelims and TYs as pipelines.

If you perform well:

- Crude probability of landing some categorical spot for PGY‑2, across the US: easily 30–60%.

- Probability of staying in the same institution: usually lower, perhaps 20–40%, depending on program size and turnover.

Case B: Prelim Surgery → Categorical GS or Anesthesia

- Categorical GS:

- Unfilled categorical GS spots exist but are fewer.

- Competition is stiff; many prelims chase the same few slots.

- If you are top‑tier among prelims (strong letters, good OR skills, high in‑service scores), your probability might be 20–30%. If you are average, it drops under 10%.

- Anesthesia:

- Many programs like surgery prelims.

- Availability of PGY‑2 slots is variable but recurrent.

- Strong prelim → anesthesia transitions succeed with rough rates 20–40% in some systems.

Case C: Prelim/TY → Highly Competitive Specialty (Derm, Plastics, ENT, Ortho, Uro, etc.)

- Available positions: minimal.

- PD expectations: near‑perfect CVs.

Even if you reapply with more publications and strong off‑service performance, the probability is low:

- 0–5% range for most applicants.

- Higher only if you are already in the top couple of percent nationally (think 260+ Step 2, strong publications in the field, heavy networking).

Case D: “Backup” Categorical → Different Categorical Specialty

Example: matched categorical IM but wanted radiology or anesthesia.

The data show:

- Most do not switch; they settle. Completion rates in IM remain high.

- Among those who actively try to switch early (PGY‑1), the success rates might run in the 10–30% range depending on metrics and geography.

There is a hard ceiling here: openings in the target field. You cannot out‑network a zero‑vacancy market.

9. How to Think About Your Risk and Options on Match Day

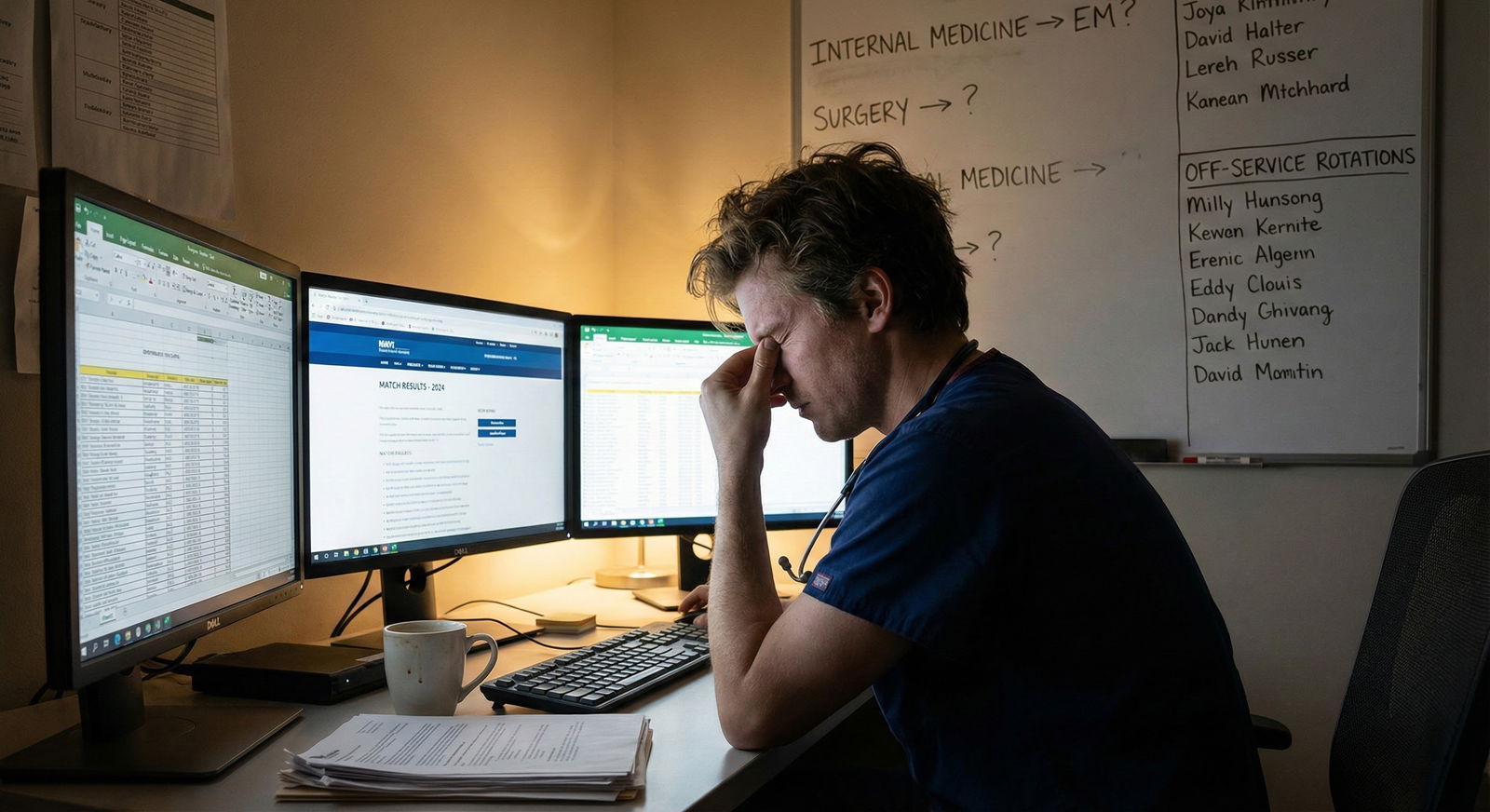

I will not sugar‑coat this. The day you open your envelope or email and see “off‑service” or “backup specialty,” your probability of ever practicing your first‑choice specialty drops sharply.

But it does not drop to zero.

If we summarize the landscape in pure probability language:

- P(ever switching specialties after matching into anything) for the average US resident: roughly 1–3%.

- P(switching when already in a high‑leak specialty and moving to a related, less competitive one): can approach 20–40% if you intentionally pursue it and you are a strong performer.

- P(switching from off‑service to a hyper‑competitive, small‑slot specialty): usually <5%, often effectively zero unless you are an outlier.

What should you actually do with that information?

- Treat your matched specialty seriously, even if it is not your dream. The median outcome is “you stay where you landed.”

- If you are genuinely unsure, behave like you have 6–9 months to gather data and decide whether to push for a switch.

- Optimize your levers: crush your current role, build relationships in your target field, be flexible on geography, and be early.

The data show that residents who approach this as a structured, numbers‑based problem—rather than as pure emotion or wishful thinking—have far better odds of ending up in a specialty that actually fits.

Key points:

- Switching specialties after matching off‑service is possible but uncommon; the realistic probability for most residents sits in the single digits, higher only when moving to related, less competitive fields with recurring vacancies.

- Your odds depend less on abstract “passion” and more on hard variables: test scores, residency performance, institutional presence of your target specialty, and how early and flexibly you pursue openings.

- Plan as if you will stay where you matched, but execute the first year as if you might reapply—because the small subset who successfully switch almost always built that option through deliberate, high‑performance behavior from day one.