Most residents are using note templates that quietly make their clinical care worse.

Let me be blunt: templates can save your sanity, your sleep, and your board certification—or they can bury you in bad data, autopopulated lies, and medicolegal landmines. The difference is not subtle. I have watched smart residents look incompetent because of garbage notes that “wrote themselves.”

You are not going to stop using templates. Nor should you. The real job is to separate clinically safe shortcuts from habits that will absolutely hurt you, your patients, and your evaluations.

Let me break this down specifically.

1. The Core Principle: Notes Are a Patient‑Safety Tool, Not a Billing Artifact

Everyone pretends notes are for communication. Administrators quietly care more about billing and compliance. Residents? You just need to survive.

Here is the hierarchy that actually matters:

- Clinical accuracy and safety

- Legibility and team communication

- Time efficiency

- Billing fluff (RVU steroids and “medical decision-making” jargon)

Any template that flips this order—putting speed or billing above accuracy—is dangerous.

Clinically safe templates do three things reliably:

- Force you to touch critical thinking elements (assessment, differential, “what changed?”).

- Make it hard to lie by autopopulation.

- Keep copy-paste to reference-level, not as a substitute for fresh thinking.

Unsafe templates do the opposite:

- Autopopulate whole exams and ROS that were never done.

- Hide what is new versus old.

- Create 2–3 page “assessments” that say nothing useful.

If your template does not make it obvious what changed in the last 24 hours, it is not serving you as a clinician.

2. Daily Progress Notes: Templates That Help vs Hurt

Progress notes are where residents quietly build or destroy their clinical reputation. Attendings judge you on three things: your sign-out, your progress notes, and how you handle pages.

A. Structure of a Clinically Safe Progress Note Template

The best progress note templates are minimal but specific. Something like:

- One‑liner

- Interval events / overnight issues

- Subjective (if relevant)

- Focused, problem‑oriented objective

- Problem‑based assessment and plan

Problem-based is non‑negotiable. System-based SOAP templates lead to unfocused thinking and “checklist medicine.”

A good internal medicine or surgery progress note template might look like this (conceptually):

- ID/one-liner

- Hospital day, postop day, code status, disposition target

- Interval events / nursing concerns / consult recs

- Vital sign trends, I/O summary, key labs/imaging (only deltas or relevant abnormals)

- Problem list with concise A/P under each problem

What you absolutely do not need:

- Full 14‑system ROS for every daily note

- Full physical exam redundantly charted daily unless relevant

- Past medical history restated every day (once is enough; reference prior)

You are not being graded on how many words you can dump into Epic.

B. Good Template Elements That Help You Clinically

These features tend to help:

One‑liner skeleton with key anchors:

“[Age] [sex] with [key comorbidities] presenting with [main problem] now [hospital day/postop day], course complicated by [major active issues].”This forces you to restate the story every day. You catch diagnostic drift. You remember why they are actually here.

Explicit “Overnight / Interval Events” line

Forces you to check nursing notes, vitals, and pages. Prevents the classic miss: “oh, she had 6 beats of VT at 3 a.m. that no one mentioned to you.”Trended vitals and key data, not full dumps

“BP 140s–170s overnight, now 150/80; HR 90–100; temp max 38.1.”

This is concise. Shows you actually looked. A template that pulls 24 lines of vitals? That is noise, not clarity.Problem-based A/P skeleton with prompts

For each active problem:- Assessment: What is your working dx? Stable/improving/worsening?

- Evidence anchor: “Based on [lab trend/symptom/exam].”

- Plan: diagnostics, therapeutics, monitoring, consults, dispo impact.

Your template can literally remind you: “Assessment (why), Plan (what), Monitoring (how we know).”

Disposition block

“Anticipated discharge: [date estimate]. Barriers: [PT/OT, placement, oxygen, insurance, family, procedure].”

This makes you think upstream. You stop waiting until day 9 to decide on rehab.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Problem-based A/P | 90 |

| Overnight Events Section | 80 |

| Disposition Block | 70 |

| Autopopulated Full Exam | 25 |

| Autopopulated ROS | 10 |

C. Dangerous Progress Note Template Habits

These are the ones that burn you:

Autopopulated full physical exams

That perfect, 12‑system normal exam at 06:58 for every one of your 18 patients? No.

If you did not test gait, lungs, neuro, skin, you do not document “normal.” Use a template that:- Only has default text for things you actually always examine.

- Forces you to free‑text anything you do not routinely assess.

Residents have been deposed over exam templates that documented normal neuro on a patient who was never examined after a subtle change.

Autopopulated ROS

The classic “10-point ROS negative except as above” that appears in every note, including the one when the patient was short of breath, with chest pain, diaphoretic, and nauseated.

Better option: a brief ROS line, specific to the current complaint, or omit entirely in daily notes unless there is a real diagnostic shift.Copying yesterday’s assessment verbatim

You can copy structure. Not conclusions. If your plan for sepsis is the same on day 3 as the admission note, you are broadcasting that you are not thinking.A safe rule: any time you copy the assessment and plan, you must add at least one sentence that explicitly references today’s new data or clinical course.

“All problems, every day” templates

Long problem lists filled with resolved issues (“hypokalemia—resolved,” “AKI—resolved,” “N/V—resolved”) clutter your thinking.

Keep resolved problems at the bottom, or better, move them to a “Resolved/Chronic-Stable” section with one summary line. Focus your daily A/P on active problems.Billing‑driven auto‑text

Templates pushed by your billing office that force you to restate every prior history, 10 ROS, complete exam, “medical decision making” paragraphs with boilerplate language. These consume time and add zero clinical safety.

Use them if your attendings insist, but strip them down. Put your real thinking at the top where you and consultants actually read.

3. Admission H&P Templates: Front‑Loading Safety, Not Fluff

H&Ps are where templates can genuinely save you—if they are structured correctly. This is the note that everyone reads. This is where wrong diagnoses get anchored.

A. Clinically Strong H&P Template Features

The H&P template that helps you:

Has a structured HPI section that nudges you through:

- Onset, progression, associated symptoms, prior episodes

- Relevant negative “can’t miss” symptoms (e.g., for chest pain: pleuritic vs exertional, positional, radiation)

- Key timelines (when they were last well, when they last took meds)

Includes a brief pre‑hospital and ED course segment:

- “In ED: hypotensive to 80s, received 2L NS, cefepime, lactate 4.2 → 2.1.”

Forces a succinct problem representation:

- One to two sentence summary with most likely working diagnosis.

Has a problem-based A/P with explicit differential for major problems:

- “Problem 1: Acute hypoxic respiratory failure—likely multifocal pneumonia vs cardiogenic pulmonary edema…”

- Not just: “Pneumonia. Continue zosyn.”

Includes a med rec block that actually forces reconciliation:

- “Home meds reviewed with: [patient/family/pharmacy]”

- “Changes: holding [X], dose adjusted [Y].”

Structures risk/safety elements:

- Code status / goals of care

- DVT prophylaxis

- GI prophylaxis (for certain services)

- Fall risk, aspiration risk (advanced age, stroke, dementia)

Templates shine here. They prevent omissions when you are sleep‑deprived and it is your fourth admission at 2 a.m.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Create new H&P |

| Step 2 | Use service specific template |

| Step 3 | Fill HPI prompts |

| Step 4 | Generate problem list |

| Step 5 | Problem based A/P |

| Step 6 | Complete med rec block |

| Step 7 | Address safety items |

| Step 8 | Finalize and review for autopopulated errors |

B. H&P Template Pitfalls That Hurt Residents

The ones I see over and over:

Bloated HPI boilerplate

Templates that insert half a page of stock “patient is a X-year-old with a history of…” plus template language about “symptoms are intermittent, non-radiating, not associated with…” that you never verified.

If it did not come from the patient, chart, or collateral, it does not belong in your HPI.Template‑driven over-documentation of irrelevant ROS

You admit a patient for sepsis and find yourself documenting “denies blurry vision, tinnitus, hair loss, joint swelling, change in shoe size” because of some generic ROS block. This wastes time and hides the important negatives.PMH/PSH/Family/Social sections that are never updated

Classic trap: copying the entire historical block from an old note without checking. Suddenly your daily thoracic surgery patient “drinks 6 beers nightly” because of a 2014 ED note, and his wife is yelling because he has been sober for 3 years.Safe rule: At admission, you own the problem list and history update. Your template should remind you “History confirmed this encounter: yes/no, changes: …”

Differential diagnosis section that remains empty

Your template has a “Differential” heading under each major problem that you never fill. That is a missed opportunity. It looks lazy. Worse, it means you are not forcing yourself to name what else it could be.No explicit “what could kill them” block

For high‑risk admits (chest pain, shortness of breath, fever in chemo patient), your template should have a prompt:- “Red flag diagnoses considered and how being ruled out: ___” It is defensive documentation. And more important, it aligns your workup with your note.

4. Discharge Summaries: The Most Misused Template in the Hospital

Discharge summaries are not for your billing office. They are for Future You (clinic follow‑up), the PCP, and the team that reads them when the patient comes bouncing back to your ED in 4 days.

A. Helpful Discharge Summary Template Structure

A good discharge template enforces:

A tight hospital course by problem, not by date:

- “# Sepsis secondary to pyelo: [course]”

- “# AKI on CKD: [course]”

- “# Atrial fibrillation with RVR: [course, interventions, decisions]”

A clear medication changes table:

- “Started: [why, who will monitor]”

- “Stopped: [why]”

- “Dose changed: [what, why]”

A follow‑up and responsibility block:

- “PCP: follow BMP in 1 week to recheck creatinine after ACEi restart.”

- “Cardiology: follow up in 2 weeks to recheck rate control and symptoms.”

A pending results section:

- “Pending at discharge: ANA, SPEP. Results to be followed by: [service/clinic].”

A code status / goals-of-care summary if any change occurred during stay.

You want the receiving clinician to be able to reconstruct the admission in 30–60 seconds. That is it.

| Component | Why It Matters |

|---|---|

| Problem-based course | Clarifies what happened and why |

| Med changes block | Prevents reconciliation errors |

| Follow-up plan | Assigns responsibility, prevents drift |

| Pending results | Avoids lost labs and incomplete workups |

| GOC/code summary | Respects patient decisions, avoids backtracking |

B. Harmful Discharge Summary Template Patterns

Things that make you look bad and create safety issues:

Autofilled “entire chart” summaries

These pull in every note, every line of vitals, and 40 labs. No one will read it. Even you will not. It also hides the signal when the patient bounces back.Generic “improved and stable” language without specifics

“Patient improved and discharged in stable condition.” From what? To what? A safer habit:- “At discharge: ambulating with walker, O2 1L at rest, able to perform ADLs with minimal assist; creatinine returned to baseline (1.1).”

No med rationale

Starting a DOAC? You need at least one sentence: “Started apixaban for new atrial fibrillation (CHA2DS2‑VASc 4).”

This matters when your patient shows up later with a GI bleed and some consultant is asking what on earth everyone was thinking.No responsible party for pending results

“Pending at discharge: cultures.” And then what? Who is calling the patient when they grow Pseudomonas? Your template should force you to name a clinic or provider.Huge copy-paste of H&P instead of a concise course

A 3‑page discharge summary that is just your admission cut‑and‑pasted is useless. The relevant question is: what happened between then and now?

5. Specialty-Specific Templates: What Actually Helps

Every service has its own documentation culture. Some have figured out sane templates; others are still in documentation hell.

A. Medicine Wards / Hospitalist

Safe, efficient templates:

- Problem-based progress notes with a robust, reusable skeleton.

- Service-specific admission templates (e.g., for CHF, COPD, DKA) that prompt for:

- Precipitating factors

- Home regimen and adherence

- Objective severity scores (e.g., CURB‑65, CHA2DS2‑VASc)

- Cross-cover note templates for night float:

- “Page reason,” “Assessment,” “Interventions,” “To‑do for day team.”

What hurts:

- Overreliance on autopopulated daily “full” physical exams.

- ROS sections that you never actually take from the patient.

- Not updating problem lists through the stay.

B. Surgery / Surgical Subspecialties

Safe templates:

- Post‑op day templates that force you to address:

- Pain, diet, flatus/BM, drains, Foley, ambulation, DVT prophylaxis, wound.

- Procedure notes with standardized language but clearly editable:

- “Findings,” “Complications,” “Specimens,” “EBL,” “Disposition.”

What hurts:

- “Postop checks” with templated “no complaints, tolerating diet, ambulating” when the patient has not eaten or gotten out of bed.

- Autopopulated “wound c/d/i” when no one pulled back the dressing.

C. ICU

Safe templates:

- System-based objective, but problem-based assessment:

- Neuro, CV, Pulm, Renal, Infectious, Heme, Endocrine.

- Built‑in prompts for:

- Sedation target, delirium screening, vent settings and goals, pressor/weaning plans, daily awakening/breathing trials, lines/tubes disposition.

What hurts:

- Massive autopopulated data dumps: 24 hours of I/O line by line, every single vent setting from the last 10 adjustments. Your template should focus on current settings and trends.

- No explicit daily “goals for the next 24 hours” section.

D. Outpatient / Continuity Clinic

Safe templates:

- Visit type–based templates (DM follow‑up, HTN follow‑up, well visit) with:

- Disease‑specific metrics: A1c, BP log, statin/ACEi, vaccines.

- Concise medication refill templates:

- Indication, last labs, last visit, next follow‑up.

What hurts:

- Templates that default “medication adherence: good” when you did not ask.

- ROS firehoses that bury your assessment in noise.

6. Copy-Paste and Smart Phrases: Safe vs Stupid

Let me be very clear: you are not going to stop copying and pasting. Nobody does. The question is whether you do it intelligently.

A. Safe Uses of Copy-Paste / Smart Phrases

These are fine, often ideal:

Reusing structured A/P skeletons across patients with the same diagnosis, while updating specifics:

- Your DKA plan, your CHF plan, your COPD exacerbation plan.

Reusing teaching text / guideline references:

- E.g., your standardized anticoagulation counseling block.

Reusing your own previous differential but updating with what has been ruled in/out:

- Makes your clinical reasoning transparent over time.

Using smart phrases for frequently repeated counseling:

- Fall risk counseling, anticoagulation, insulin use.

B. Unsafe Copy-Paste Behaviors

Red flags:

Copying someone else’s exam or assessment

If you did not examine it, do not chart it. Copying forward an attending’s note that said “no JVD, lungs clear, no edema” when the patient now has crackles and 3+ edema is textbook bad medicine.Not editing obviously outdated statements

“Patient denies chest pain” on the day they are in cath lab.

“No fever” on the day of a 39.5 spike.

These are credibility killers and medicolegal problems.Copying old medication lists without reconciling

Never trust pre‑populated med lists. They are wrong often enough to hurt people. Your template should force a “med rec updated: yes/no” line.Copying full H&P into every progress note

Nobody wants to scroll past your entire admission story to see what changed today. It slows the whole team down and hides key updates.

7. Building Your Own Safe Templates: A Practical Playbook

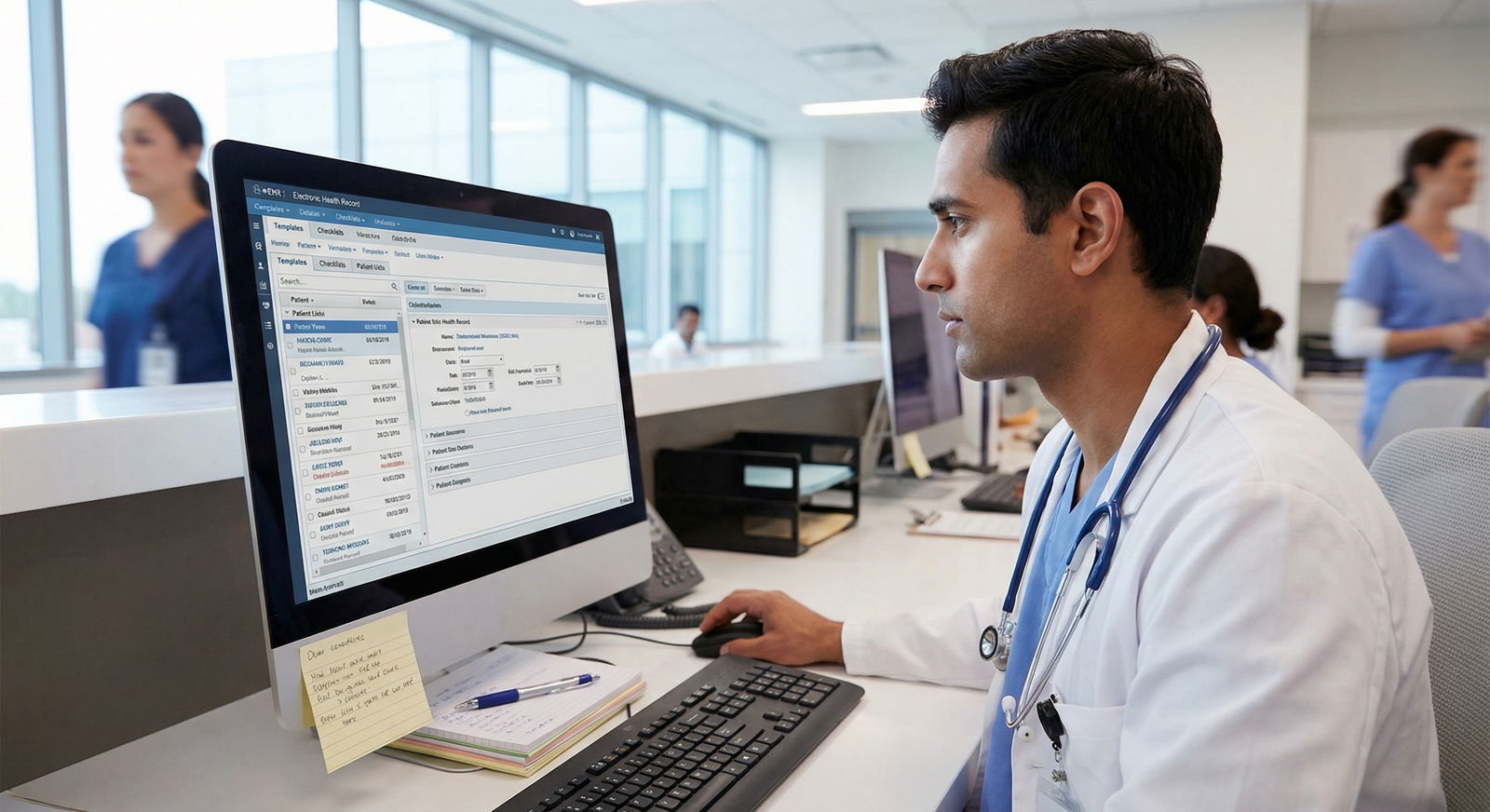

You do not need to wait for your program to hand you good templates. You can build smart ones inside Epic/Cerner/whatever in under an hour and use them for the rest of residency.

A. Start with One Service and One Note Type

Pick:

- Medicine wards progress note

- Or ICU daily note

- Or your most common admission H&P

Do not try to fix everything at once.

B. Decide Your Non‑Negotiables

For a daily progress note, for example, your template might have:

- ID/one-liner

- Hospital day / service / code status / dispo target

- Overnight events

- Focused objective and data

- Problem-based A/P with prompts for assessment, evidence, plan, monitoring

- Disposition/safety block (DVT prophylaxis, lines/tubes, PT/OT, follow‑up needs)

C. Keep Autotext Minimal and Honest

Use autotext only for:

- Section headings

- Prompts (e.g., “Assessment: ___. Evidence: ___. Plan: ___.”)

- Truly universal exam elements you always perform

Do not preload whole normal exams or entire plans. Leave brackets or blanks that you must consciously fill.

D. Borrow and Iterate

Look at the best intern or senior’s notes on your service. Not the wordiest—the clearest. Ask them to share smart phrases or templates. Steal aggressively, then refine.

Every week, change one thing that annoys you. Over a month or two, you will have a template that feels like an extension of your thinking rather than a bureaucratic chore.

8. How Templates Affect Your Evaluations and Reputation

This is the part residents underestimate.

Attendings do not have time to shadow you all day. They judge your clinical reasoning from:

- How you present

- How you respond to overnight issues

- How you write notes

If your notes are consistently:

- Problem-based

- Clear about what changed

- Explicit about your thinking and next steps

You get labeled as “strong,” “organized,” “good clinical judgment.”

If your notes are:

- Cluttered with autopopulated junk

- Inconsistent with the physical exam or vitals

- Copy-pasted day after day

You get labeled as “disorganized,” “scattered,” or “does not reassess plans.” Even if your actual bedside care is fine.

The hidden advantage of safe, sharp templates: they showcase what you are already doing in your head. That pays off in letters, rankings, and fellowship applications.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Resident A | 2,2 |

| Resident B | 3,4 |

| Resident C | 4,5 |

| Resident D | 5,5 |

| Resident E | 1,2 |

(X‑axis: subjective note quality 1–5, Y‑axis: perceived clinical performance 1–5, as rated by attendings.)

FAQs

1. Is it ever acceptable to use a fully templated normal physical exam?

Only if it matches what you actually did and you routinely examine those systems on that encounter type. For most inpatient progress notes, a completely templated “normal” multi‑system exam is dishonest. Create smaller chunks (e.g., “lungs CTAB, no wheezes/rales/rhonchi”) for systems you reliably check, not a 10‑system block.

2. How much can I safely copy from my own previous notes?

Copy structure freely, copy data cautiously, copy conclusions almost never. If you copy an A/P, you must update it with today’s labs, imaging, symptoms, and your revised assessment. As a rule, your copied section should look different by the time you finish editing it.

3. Do I really need a full ROS on admissions?

No. You need a targeted, high‑yield ROS driven by the chief complaint and major comorbidities. A template that forces you through 14 systems is a billing artifact. Focus on can’t‑miss negatives (e.g., chest pain, dyspnea, neuro deficits, GI bleeding) relevant to the presentation.

4. What is the safest way to handle autopopulated med lists?

Treat pre‑populated med lists as suggestions, not truth. Your template should include “Med rec completed with: patient / family / pharmacy / SNF / unknown” with a line for discrepancies. Delete meds you confirm are not current. Add start/stop rationales for major changes.

5. How long should a good medicine progress note be?

For most stable or moderately complex ward patients: ½ to 1 page of real content. If it routinely runs to 2–3 pages, you are either over‑templating, over‑copying, or padding. ICU and extremely complex patients may need more, but the key test is: can someone understand the last 24 hours and your plan in under a minute?

6. My program’s mandatory templates are awful. What can I realistically do?

You are stuck with some structural requirements, but you still control:

- Where your clear one‑liner and problem-based A/P appear (put them at the top).

- How much autopopulated junk you delete before signing.

- Your own personal smart phrases layered on top of the mandated template.

Quietly build a lean, clinically focused skeleton inside the required framework. Attendings will read the parts you craft, not the legal boilerplate your system injects.

Key points, distilled:

- Clinically safe templates are problem‑based, force daily fresh thinking, and avoid lying via autopopulation.

- The worst offenders are full templated exams, templated ROS, and lazy copy‑paste of old assessments that no longer match reality.

- Build and refine your own focused templates; they will make you faster, safer, and look smarter—for the rest of residency.