Step 3 is not “Step 2 CK on easy mode.” That belief is exactly why smart people get burned by this exam.

I keep hearing the same line on wards: “Don’t worry about Step 3, it’s just Step 2 again but with management.” That’s wrong in three ways: it underestimates the difficulty, misunderstands what’s actually tested, and leads people to study in completely the wrong way.

Let’s pull this apart with facts, not folklore.

The Data: Step 3 Is Not Just Another Knowledge Test

There’s a reason the NBME doesn’t just call it “Step 2 CK Part II.”

Step 2 CK asks: Do you know what to do?

Step 3 asks: Can you actually run the case without hurting anyone, over-testing, or missing the diagnosis while time passes?

Different question. Different skill. Different failure patterns.

Look at how the exam is built. The public content outlines and examinee performance data make this pretty obvious if you bother to read them instead of just listening to that PGY-3 who “skimmed UWorld on nights and was fine.”

On Step 3, your score comes from two distinct components:

| Feature | Step 2 CK | Step 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Format | MCQs only | MCQs + CCS cases |

| Days | 1 | 2 |

| Case simulations | None | ~13 computer-based cases |

| Focus | Diagnosis + next step | Longitudinal management + systems |

Now add the pass rates. They’re high because the pool is filtered, not because the test is trivial. In 2023, Step 3 first-time pass rates for US MD grads were around the mid‑90% range; DOs similar; IMGs lower. That’s after years of selection. And yet, every single cycle, I see residents scrambling for retakes because they treated it like a recycled CK.

The real trap isn’t that Step 3 is impossibly hard. It’s that it’s different enough that a CK-style cram strategy leaves holes big enough to fail through.

Myth #1: “If You Did Well on Step 2 CK, You Don’t Need to Study Much”

I’ve watched this movie. Many times.

PGY-1, did great on Step 2 CK (250+), goes into Step 3 with a half-finished UWorld block history and “I’ll just rely on my foundation.” Comes out stunned: “That was way weirder than I expected.” Some pass. Some don’t. The “foundation” story only works if your day-to-day residency work constantly reinforces outpatient, inpatient, OB, peds, psych, health systems, and prevention. Spoiler: it doesn’t.

Step 2 CK primarily tests whether you can identify the right diagnosis and immediate next step. Snapshot problems. You get 2–3 lines of history, some labs or an image, then: “what’s the next best step?”

Step 3 absolutely has those. But the exam is built around a different core question: Can you safely and efficiently manage a patient over time, in the real healthcare system, with limited information and constraints?

That changes everything:

- It cares more about cost-effective care, not just correct care.

- It punishes over-testing and unnecessary admissions.

- It cares if you can anticipate complications and follow up.

- It expects you to think like someone who’s been the primary, not just the consultant.

Step 2 CK performance is a good predictor of Step 3 performance, statistically. But correlation is not a study plan. The NBME correlation data only tells you that on a population level, stronger test-takers tend to stay stronger. It does not mean your individual score is “locked in” or that you can dial your effort down to 20%.

The residents who underperform Step 2 CK by the largest margin on Step 3 usually have the same story: “I thought it’d be a lighter version of what I already did. I underestimated the CCS. I didn’t review outpatient or psych. I didn’t practice thinking longitudinally.”

They didn’t fail because Step 3 is some mystery beast. They failed because they prepared for the wrong exam.

Myth #2: “The CCS Cases Are Just Long Vignettes”

They’re not vignettes. They’re simulations. That word matters.

If Step 2 CK is “What’s the next best step?” then CCS is “Run this patient’s care like you’re actually the doctor, and we’re watching.”

Here’s where people screw this up badly: they think CCS is about reproducing algorithms they memorized. In reality, it tests whether you understand sequence, safety, and timing.

For example, a typical mistake pattern I see in practice cases:

- Resident orders: CBC, CMP, CT, MRI, echo, TTE, TEE, colonoscopy, full autoimmune panel in the first five minutes because “more data is safer.”

- Forgets basic things: vitals q1h, NPO when it’s clearly surgical, IVF when hypotensive, pain control.

- Doesn’t move the clock after ordering urgent tests, so treatment is delayed.

- Leaves the patient in the ED for 24+ “simulated hours” with no admit order.

- Never reassesses after new results. Just keeps adding tests.

On paper, that’s a highly knowledgeable person. On CCS scoring, that’s someone who’s unsafe, inefficient, and not functioning like a real resident.

You’re being scored not only on what you do, but:

- How quickly you stabilize the patient.

- Whether you do things in a physiologic and logical order.

- Whether you use appropriate settings (ED vs floor vs ICU vs clinic).

- How you adjust when new data appears.

- Whether you stop when enough info has been gathered.

Is that “just Step 2 CK, but longer?” No. That’s a different cognitive domain.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Step 2 CK | 80 |

| Step 3 MCQs | 60 |

| Step 3 CCS | 30 |

The more you’ve only trained your brain to sniff out the board-style “buzzword sentence” and click the best option, the more the CCS will expose the gaps in your actual management flow.

Myth #3: “Content Is the Same — Just Medicine, OB, Peds, Psych”

Content overlap? Yes. Same exam? No.

The blueprint shifts in ways that matter. Step 3 leans harder on:

- Outpatient management. Chronic diseases, follow-up, screening intervals, long-term complications, med titrations.

- Public health and systems. Vaccines, case reporting, occupational exposures, population-level thinking, resource use.

- Ethics and communication. Consent, capacity, surrogate decision-makers, confidentiality with minors, impaired colleagues.

- Safety and errors. What you do after a mistake, not just how to avoid it.

Step 2 CK absolutely touches these, but Step 3 pushes them toward “you’re now the responsible physician, not just the student parroting guidelines.”

I’ve watched strong Step 2 CK folks get chewed up by questions like:

- When can this 16-year-old consent alone?

- Do you call CPS or handle within the family?

- Do you discharge with close follow-up or admit for social reasons?

- How do you respond after you gave the wrong dose, but the patient is fine?

These are scenarios your “FA + UWorld + Anki” CK brain isn’t trained for, because they rely heavily on context you usually hand-wave on practice questions.

Myth #4: “You Can Just Re-Do Step 2 UWorld and Be Fine”

Recycling Step 2 CK prep is exactly how you get a very average Step 3 performance from a strong Step 2 base.

The problem isn’t that Step 2 questions are useless. Knowledge is knowledge. The problem is the way they train your brain. You’re conditioned to:

- Hunt buzzwords.

- Ignore extraneous info.

- Think in a hyper-compressed, 30-second question cycle.

That’s almost the opposite of how you have to think on CCS and quite different from the longer, multi-layered vignettes that probe follow-up and system issues.

If your Step 3 prep looks like “I did some random CK questions on my phone between patients, I’m good,” then you’re essentially doing endurance training for a sprint event, and vice versa.

Here’s what data and actual experience say works better:

- Use a Step 3-specific question bank. Because the pattern of questions matters, not just the raw facts.

- Do timed, exam-length blocks. Build stamina for 7+ hours, not casual 10-question phone-and-coffee sessions.

- Actually learn the CCS interface. Click through the tutorials. Practice moving the clock, admitting, ordering, re-evaluating.

- Pay specific attention to outpatient and psych if your residency is inpatient-heavy. Those are classic blind spots.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Step 3 Qbank | 45 |

| CCS Practice | 30 |

| Review of Weak Specialties | 20 |

| Random Cramming | 5 |

Notice what’s not there: “Re-do all of Step 2 UWorld from scratch.” Not because it’s harmful. Because it’s inefficient and misaligned with how the test actually behaves.

Myth #5: “Step 3 Is Low Stakes — Programs Don’t Care”

This one’s half-true in the most dangerous way.

Attending-level truth: many programs don’t obsess over Step 3 scores the way they did for Step 1. But they absolutely care about Step 3 failures. Ask any PD who had to explain to the department chair why a resident isn’t independently licensed on time.

Common downstream consequences I’ve seen:

- Delay in full medical licensure for moonlighting.

- Administrative headaches for J‑1 or H‑1 visas.

- Extra remediation, meetings, and “development plans.”

- Quiet—but real—questions about your reliability and test-taking.

No, failing Step 3 doesn’t end your career. But it creates friction at exactly the time you want things to be smooth: early residency, when you’re struggling to just stay afloat clinically.

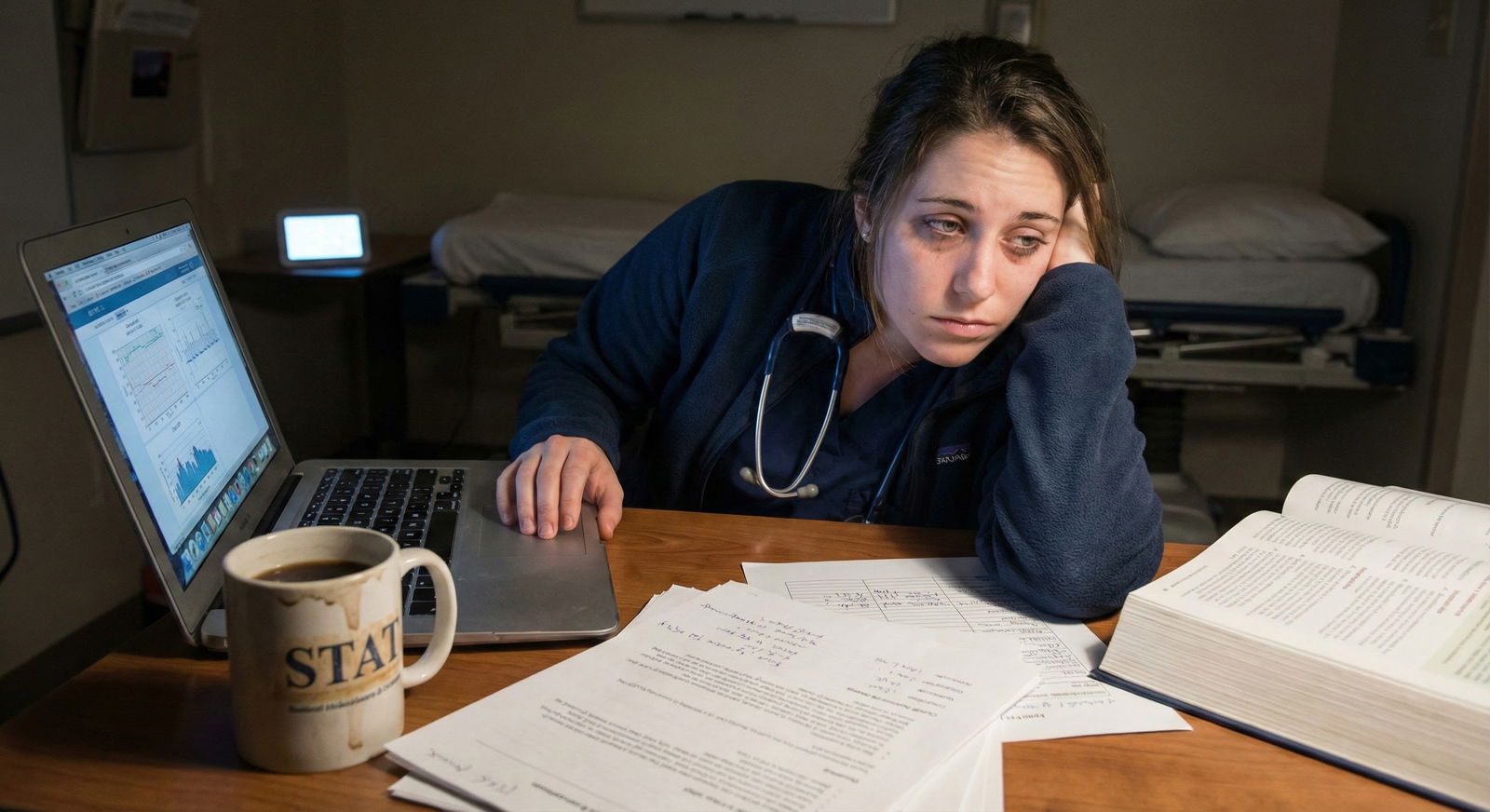

What people miss is the timing problem. You’re taking Step 3 when your bandwidth is lowest. Night float. Q4 call. ICU months. You’re not a third-year with 8 weeks of protected time. You’re a resident trying to find 60–80 hours to study across two or three months of chaos.

Step 3 is “easier” content done under much worse conditions. That’s the trap.

So What Actually Distinguishes Step 3 From Step 2 CK?

Let me put the contrast clearly, because this is where the myth falls apart.

Step 2 CK asks:

“Can this person identify the right diagnosis and immediate next step in a controlled setting, based on guidelines and core clinical knowledge?”

Step 3 asks:

“Given this same knowledge base, can this person:

- Take responsibility for the whole case?

- Use resources wisely?

- Anticipate next steps over hours to months?

- Avoid harms from both omission and overuse?

- Function inside the real-world constraints of healthcare systems?”

That’s not “just Step 2 again.” That’s a shift from knowledge demonstration to practice simulation.

The multiple-choice portions move in that direction with more systems, ethics, and longitudinal framing. The CCS cases shove you into it headfirst.

How To Prepare Like You Understand This Difference

If you want to actually benefit from this myth-busting instead of just nodding and going back to Reddit, align your prep with the real exam:

- Treat CCS as non-negotiable, not an afterthought. Do enough cases that ordering vitals, nursing orders, location (ED vs admit vs ICU), and follow-up become automatic.

- Anchor yourself in “safety first, then efficiency, then elegance.” Stabilize, then investigate, then refine.

- Practice outpatient thinking if you’re living in the hospital. Diabetes follow-up, hypertension titration, cancer screening, contraception, psych meds, addiction care.

- Read the ethics and systems questions carefully. There’s often no lab or imaging “hook.” The whole question is the nuance.

And above all, stop saying “It’s just Step 2 CK again.”

That little sentence is how you give yourself permission to under-prepare, to ignore CCS, to skip the outpatient stuff because “I’ll wing it,” and to walk into a two-day exam thinking it’s a nostalgic rerun instead of a slightly different show.

Step 3 is not dramatically harder than Step 2 CK in raw content. But it’s different enough that pretending they’re the same is like training for a 5K and then being surprised when a half-marathon feels rough. Same sport. Very different experience.

Years from now, you won’t remember your exact Step 3 score. You will remember whether you treated it seriously enough to get licensed cleanly, on time, without drama—and whether you finally started thinking like the doctor the exam assumes you already are.