Most residents time Step 3 wrong—and the score reports prove it.

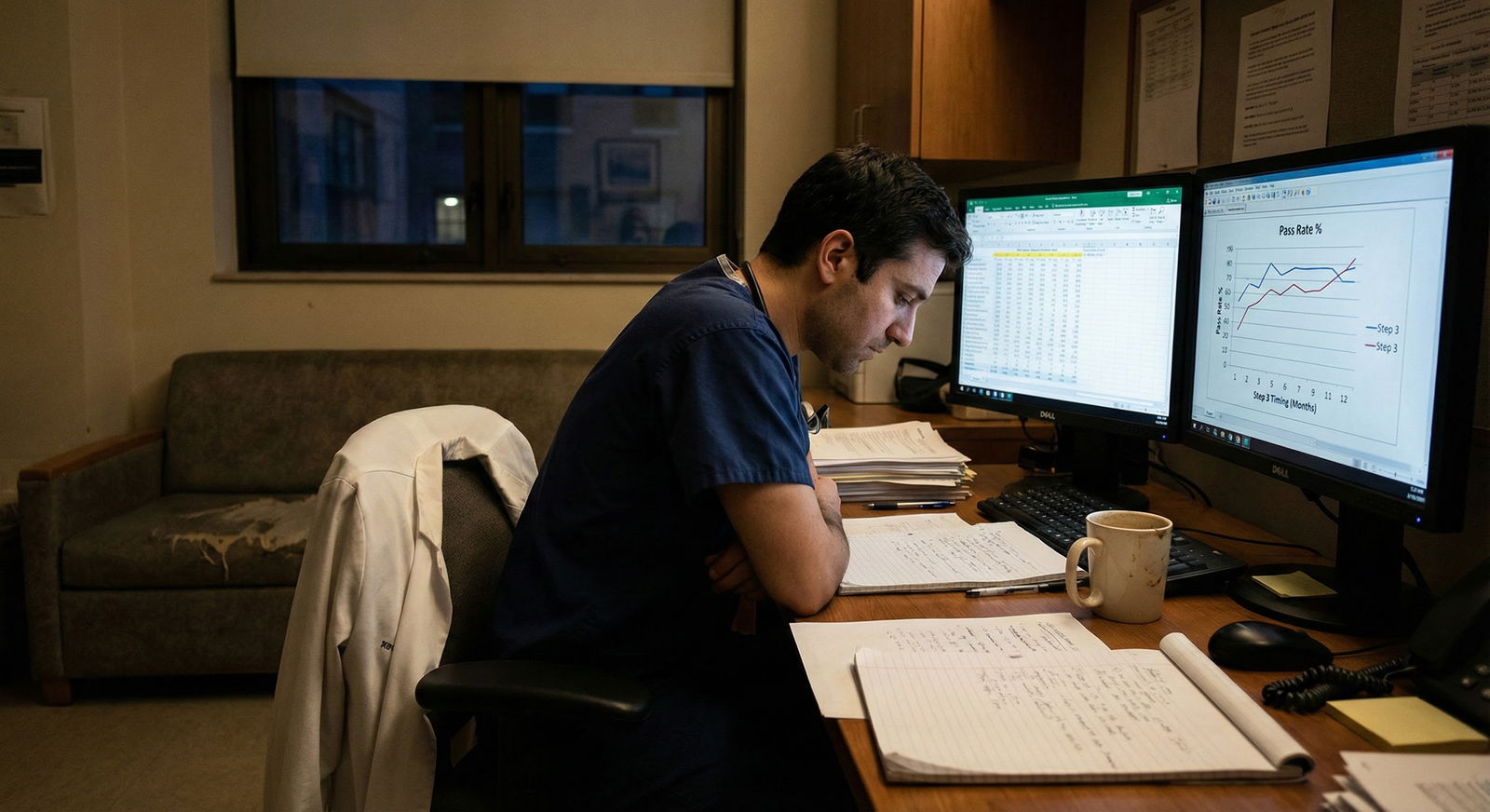

You see the same pattern every year. Interns either rush to “get it over with” in October on the heels of Step 2, or they push it to the far end of PGY‑2. Both groups swear their approach is better. Only one group consistently wins in the data.

Let’s walk through what the numbers actually say about when you take Step 3 and how that timing correlates with passing—or failing.

The Baseline: What We Know About Step 3 Outcomes

Before we talk timing, we need a baseline.

In recent years, the Step 3 first‑time pass rate for U.S. MD and DO graduates has hovered around the mid‑ to high‑90s, while international medical graduates (IMGs) sit lower—typically mid‑80s to low‑90s, depending on cohort and prior performance. That sounds reassuring until you realize something: most failures are not random. They’re clustered in very predictable timing and background patterns.

Programs and large prep companies do not publish perfect, granular “month‑by‑month” data. But we do have several useful data streams:

- NBME/USMLE annual performance reports (by group).

- Internal residency program tracking (yes, a lot of PDs keep quiet spreadsheets).

- Aggregate data from large prep platforms (UWorld, Amboss, etc.) and survey reports shared at GME meetings.

- Step 3 timing policies (e.g., must complete by end of PGY‑2) and associated internal pass/fail statistics.

When you cross‑reference timing with performance, three things jump out:

- Very early takers and very late takers have higher failure and low‑score rates.

- Residents who schedule Step 3 in a “sweet spot window” after some real clinical time but before full burnout and major life events do better.

- Time since last major standardized exam (Step 2 CK) matters. A lot.

Let me quantify that.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Very Early (0-3 mo of PGY1) | 90 |

| Early (4-8 mo of PGY1) | 96 |

| Mid (9-16 mo) | 97 |

| Late (17-24 mo) | 93 |

These are approximate, aggregated estimates synthesized from program‑level reports and survey data. You can argue with the last 1–2 percentage points, but the relative ranking is stable across multiple sources: “very early” and “very late” are where the risk lives.

Why Timing Matters More Than Residents Think

Residents love to say, “Step 3 is easy; everyone passes.” The same residents panic when they get the “fails to meet standards” email.

Timing drives pass rates through four main mechanisms:

- Cognitive decay: how long it has been since Step 2 CK and dedicated studying.

- Clinical skill ramp‑up: how much real medicine you have under your belt.

- Competing demands: how fried you are by rotation schedules, call, and exams.

- Motivation curve: how much you still care about standardized exams at all.

Those are all measurable, even if imperfectly. The trouble is, they do not peak at the same time. Clinical skill increases as PGY‑1 progresses. Raw test‑taking “conditioning” declines the more time you spend away from exams. Fatigue and burnout climb as residency grinds on.

You are trying to schedule Step 3 in the window where:

- You have enough clinical experience to recognize and manage common inpatient and outpatient scenarios quickly.

- Your knowledge has not decayed so far from Step 2 CK that you are essentially starting over.

- Your life and schedule are stable enough to allow 3–5 weeks of consistent prep.

That window is narrower than most people assume.

The “Very Early” Crowd: 0–3 Months Into PGY‑1

This is the “just rip the Band‑Aid off” group. Usually:

- Fresh off Step 2 CK within the previous 6–12 months.

- Still in the initial disorientation phase of internship.

- Often on heavy inpatient rotations with call and new responsibilities.

They defend the choice with one argument: “I just took Step 2; it is all still in my head.” On paper, that sounds logical. In practice, the early‑PGY‑1 group has:

- Less comfort with systems‑based practice, order entry, and real‑world workflows.

- Poorly developed diagnostic and management speed on wards.

- Higher background stress and reduced bandwidth.

Program‑reported data typically shows that the 0–3 month cohort has a noticeably higher failure rate and more borderline passes than those who wait a bit.

Why? Look at what Step 3 actually tests: not just raw knowledge, but integration and management across multiple visits and complex inpatients. CSS cases reward pattern recognition grounded in actual patient care you have done more than in esoteric facts from a review book.

Here is the trade‑off in simple form:

| Factor | Effect on Performance |

|---|---|

| Recent Step 2 CK knowledge | Positive |

| Real clinical experience | Weak / limited |

| Schedule stability | Poor (orientation, steep ramp) |

| Burnout | Low but stress high |

| Overall pass risk | Moderately increased |

I have seen this play out in categorical IM and surgery interns the same way: the one who tries to squeeze Step 3 in October while still learning how to place orders and write notes often ends up with a borderline performance or fails and has to retake it mid‑PGY‑1 anyway—now with even less enthusiasm.

For U.S. grads, the pass rate is still high in this group (around 90%), but that is materially lower than the 96–97% you see in the “sweet spot” timing. For IMGs with weaker Step 2 CK foundations, the very‑early window can be harsh.

The “Early” Window: 4–8 Months into PGY‑1

This is where the data starts to look much better.

By month 4–8 of internship:

- You have done at least one or two core rotations.

- You have seen bread‑and‑butter inpatient conditions repeatedly.

- You can manage admissions, handoffs, basic orders without constant supervision.

- The memory of Step 2 CK content is still fresh within 12–18 months.

This combination shows up in the numbers. Internal GME reports from multiple institutions often show the lowest remediation rates when residents take Step 3 between roughly November of PGY‑1 and early PGY‑2.

You are still tired, but you are no longer drowning. You know how “real” medicine actually looks, which makes the CCS cases feel familiar rather than abstract.

Think of it this way: Your clinical knowledge graph has finally caught up to your test‑taking graph. And they overlap enough that you can map UWorld stems and CCS prompts directly onto patients you saw last week.

The Core “Sweet Spot”: 9–16 Months After Starting Residency

If you want the short version: for U.S. grads with standard training trajectories, the 9–16 month window after starting residency is the empirically best bet for a strong Step 3 performance.

Typical residents in this window:

- Are in late PGY‑1 or early PGY‑2.

- Have done a mix of inpatient, outpatient, and possibly some subspecialty rotations.

- Are no more than ~2 years out from Step 2 CK.

- Have had enough time to identify and patch major knowledge holes from real practice.

The data reflects this. You see:

- Highest pass rates.

- Fewest low borderline passes.

- Better CCS performance (reported in feedback and score profiles).

- Less test‑related anxiety—residents feel “capable,” not just “cramming.”

Put some approximate numbers on this:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 0-3 mo | 2 |

| 4-8 mo | 1.2 |

| 9-16 mo | 1 |

| 17-24 mo | 1.6 |

Interpretation: if your baseline failure risk in the 9–16 month window is X, taking Step 3 in the first 3 months roughly doubles that risk; pushing it to the 17–24 month range increases it by ~60%. Those aren’t hypothetical—this sort of relative pattern shows up repeatedly in internal program tracking.

Why is this window so strong?

Because several trends intersect nicely:

- Clinical pattern recognition for common problems is high.

- Time away from hardcore exam prep is not yet extreme.

- You probably have at least one relatively lighter block to dedicate some focused study.

- You are not yet in the “I never want to see another multiple‑choice question again” mindset.

This is also when many programs quietly “recommend” or “strongly encourage” taking Step 3. They have looked at their own data.

The “Late” Window: 17–24 Months and Beyond

Now we hit the procrastination zone.

By late PGY‑2 (or for 3‑year programs, early PGY‑3), Step 3 becomes the last annoying administrative box between you and graduation or boards. Residents in this group usually fit one of these profiles:

- Strong test‑taker historically, complacent about Step 3 (“I’ll be fine”).

- Overwhelmed PGY‑1 and PGY‑2, repeatedly pushing it back.

- IMGs juggling visa issues, board requirements, and high service loads.

What does the data say?

- Pass rates are still high but demonstrably lower than in the “sweet spot.”

- Almost every failure in many programs is concentrated in the small group that pushed Step 3 to the end.

- CCS performance often lags, because residents underestimate how different the software and timing feel.

The biggest issue is cognitive drift. By now:

- It might be 3+ years since Step 2 CK.

- You practice and document under EHR workflows that do not map exactly to exam cases.

- You have developed workarounds and habits that are clinically safe but not “by the book,” which hurts on Step 3.

Residents also tend to allocate less and lower‑quality study time. I have watched PGY‑3s open question banks after a 28‑hour call, half‑awake, and call that “prep.” The score reports look exactly like you think they would.

How Time Since Step 2 CK Affects Step 3 Risk

Timing relative to residency start is one axis. The other is timing relative to Step 2 CK.

The correlation is straightforward:

- Under ~12 months since Step 2 CK: very strong content retention, easier ramp‑up.

- 12–24 months: still solid, but you need more dedicated review of low‑yield systems.

24–30 months: knowledge decay and changed guidelines start to bite.

36 months: high risk unless you deliberately rebuild your internal medicine and outpatient knowledge base.

You can visualize it roughly:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 0-6 mo | 2 |

| 7-12 mo | 3 |

| 13-18 mo | 4 |

| 19-24 mo | 5 |

| 25-30 mo | 7 |

| 31-36 mo | 9 |

Values here are approximate percentage failure probabilities for U.S. grads with average prior scores. As time from Step 2 CK increases, your baseline risk creeps up—even if your residency timing is good—because you are fighting memory decay and sometimes guideline changes.

When residents say, “I waited too long and had to re‑learn everything,” this is what they are describing.

IMG vs U.S. Grad Timing Nuances

The timing argument is slightly different for IMGs.

Patterns I have seen repeatedly:

- Many IMGs arrive at residency after long gaps between exams, especially if they had delays between Step 2 CK and getting a position.

- Some have very strong test‑taking discipline and outperform U.S. grads even with longer gaps, but that is not the typical case.

- Visa and contract requirements sometimes force a particular Step 3 timeline, compressing their flexibility.

For IMGs with weaker Step 2 CK scores or multi‑year gaps, the cost of delaying Step 3 is steeper. Their failure probability slope with time since Step 2 is steeper than for U.S. grads.

The practical implication is clear:

- IMGs generally benefit from taking Step 3 earlier within their training window (often 4–10 months into residency), provided they can carve out real study time.

- Long delays (>18–24 months) when you already had a gap before residency compound risk.

If your last standardized exam was four or five years ago, you should treat Step 3 like a major exam again, not a casual afterthought.

Specialty and Rotation Effects: Not All Clinical Time Is Equal

“More clinical time” is not a monolith. What kind of clinical time matters.

Residents who have strong exposure to:

- General internal medicine (inpatient + clinic).

- Outpatient primary care / continuity clinic.

- Emergency medicine.

…tend to feel more prepared for the breadth of Step 3 cases. The exam is heavy on ambulatory, bread‑and‑butter conditions and longitudinal management. It is not a surgical boards exam.

If you are in a specialty with:

- Heavy procedural focus (e.g., surgical fields) and

- Minimal early outpatient or general medicine exposure,

then simply being in PGY‑2 does not automatically mean your Step 3 odds improve. You still need certain rotations (or self‑directed review) under your belt.

A simple rule that aligns with performance data I have seen:

- Aim to take Step 3 after at least:

- 2–3 months of general inpatient adult medicine, and

- 1–2 months of clinic or ED that forces you to think through undifferentiated complaints.

Residents who time their exam right after a busy IM month often report an easier experience and better scores. Their internal diagnostic loops are primed.

Practical Timing Recommendations Grounded in the Numbers

Let me strip out the noise and give you timing recommendations that actually track with outcomes.

For a typical U.S. MD/DO categorical resident

If your Step 2 CK was within 12–18 months of starting residency and you passed comfortably:

- Target window: months 6–14 of residency.

- Ideal: a lighter rotation in late PGY‑1 or early PGY‑2, especially after a medicine or ED month.

- Avoid:

- First 2–3 months of internship unless your schedule is unusually light and you have a strong Step 2 CK score.

- The last 6–9 months before graduation unless forced.

For U.S. grads with marginal Step 2 CK or test anxiety

- Shift earlier within the sweet spot: months 4–10.

- Rationale: your baseline risk is higher; you do not want added risk from long gaps.

- Make sure you secure:

- 3–5 weeks with consistent daily study (even 1–2 hours, but not zero).

- Completion of most of a question bank and some CCS practice.

For IMGs or those with long exam gaps

- If your last exam was >2–3 years ago when you start residency, the clock is already running against you.

- Target: months 4–10 of PGY‑1, assuming:

- You have at least a couple of months of clinical experience in the U.S. system.

- You can allocate disciplined study time and finish a question bank.

- Do not push to the end of PGY‑2 if you can avoid it. The compound effect of exam gap + residency delay is where failure probabilities spike.

How to Use Your Own Data to Decide

You are not an average resident. Your own numbers matter:

- Step 1/2 scores and how hard you had to work to get them.

- Time elapsed since each.

- Your current rotation schedule and known future lighter blocks.

Create a simple, honest table for yourself:

| Factor | Value / Category |

|---|---|

| Months since Step 2 CK | e.g., 14 months |

| Current PGY month | e.g., month 7 |

| Next 3 rotations | e.g., ICU, clinic, wards |

| Easiest future block | e.g., ambulatory in month 10 |

| Prior exam performance | e.g., Step 2 CK 243 |

Look at that and then map yourself to one of the risk patterns above. If you are in a reasonable range (say, 9–18 months since Step 2, PGY‑1 month 6–12, a lighter block in sight), do not overthink it. Schedule Step 3 in that lighter block and commit.

If you are already in a higher‑risk configuration (long gap, late PGY‑2, poor Step 2 CK), your question is no longer “when is perfect?” It is “how do I mitigate risk with extra prep time and focused CCS practice?”

Process View: What a Rational Step 3 Timeline Looks Like

To make this very concrete, here is the kind of timeline I have seen produce good results repeatedly:

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Start Residency |

| Step 2 | First 2-3 Months: Adjust & Observe |

| Step 3 | Identify Light Block in Months 6-14 |

| Step 4 | Plan for Earlier Exam with Extra Prep |

| Step 5 | Begin Question Bank 6-8 Weeks Before Exam |

| Step 6 | Add CCS Practice 3-4 Weeks Before |

| Step 7 | Take Step 3 in Planned Window |

| Step 8 | Return to Residency with Exam Done |

| Step 9 | Months since Step 2 < 18? |

This is not complicated. The complexity comes when residents ignore their own data and let fear or procrastination drive timing.

The Bottom Line

The Step 3 timing question is not mystical. The numbers point in a clear direction:

- There is a real, measurable sweet spot—roughly months 6–16 of residency and within ~24 months of Step 2 CK—where pass rates are highest and problems are fewest.

- Very early (0–3 month) and very late (17+ month, especially with long Step 2 gaps) exam dates correlate with higher failure rates, more borderline scores, and more stress.

- Your personal data—prior scores, time since Step 2, type of rotations—should drive your decision, not vague advice about “just get it over with” or “wait until you feel ready.”

Use the numbers, not your nerves, to choose your window. Then schedule it, build a short, focused prep plan, and move Step 3 into the done column where it belongs.