The attendings are already judging your Step 3 habits. Long before your score report shows up.

They are not scrolling through your UWorld stats or asking how many blocks you did yesterday. They are watching when you crack open that question bank on call, how you react to getting pimped on bread‑and‑butter cases, how you use downtime, and whether your “studying” is actually making you safer to work with—or just padding your ego.

Let me walk you through what faculty actually notice about your Step 3 preparation. The stuff they talk about in workrooms and at Clinical Competency Committee (CCC) meetings. The part nobody puts in the handbook.

The First Thing Faculty Clock: Your Timing

Here’s the ugly truth: faculty can tell—within a week—whether you’re the “responsible planner” or the “oh crap, my permit expires in 3 weeks” type.

On service, this shows up in painfully obvious ways.

They notice:

- The intern who, in September, casually mentions, “I’m spacing out UWorld over the next few months so I’m not cramming on nights.”

- Versus the one in March suddenly begging to move clinic days because “I really need time to study for Step 3.”

Let me be blunt: late crammers scare attendings. Not because Step 3 itself is so sacred, but because poor planning around exams is usually the same poor planning that shows up in discharge delays, missed follow-up, and half‑finished notes.

They’re not thinking, “Will you pass Step 3?”

They’re thinking, “Are you the kind of physician I trust with more responsibility?”

Here’s the internal calibration they’re using:

| Pattern They See | Silent Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Starts studying early PGY1, steady pace | Reliable, organized, probably safe to give more autonomy |

| Starts ~2-3 months before test, consistent | Normal, functional, no concerns |

| Sudden frantic cram near permit expiration | Poor planning, possible professionalism/organization issue |

| Keeps pushing exam back repeatedly | Avoidant, may struggle when stakes get higher |

They may never say this to your face. But I’ve watched more than one CCC meeting where someone says, “Remember, they almost expired their Step 3 permit. That came up during orientation too.”

It sticks.

What They Really Think About Your Question Bank Obsession

Residents love flexing UWorld block counts like CrossFit people love talking about deadlifts.

Faculty? They do not care how many questions you say you did.

They care about how your studying changes what you do with actual patients.

I’ve watched this play out on rounds more times than I can count:

You: “I’ve done like 1200 UWorld questions already.”

Attending: “Okay. Let’s see it. What’s your next step in management for this 32‑year‑old with new‑onset headache and papilledema?”

If your answer is confident, structured, and logical, they nod and move on.

If you freeze? That “1200 questions” line becomes a red flag, not a flex.

Faculty are watching for three things around your question bank use:

Are you building clinical frameworks—or just memorizing answer choices?

The resident who says, “This is classic for preeclampsia with severe features; I’d start magnesium, control BP, and plan for delivery depending on GA” signals real integration.

The one who says, “UWorld said the answer was magnesium” signals shallow pattern-matching.Do you translate learning into your notes and orders?

When your assessment and plan suddenly becomes tighter—more specific meds, better monitoring parameters, clearer disposition—faculty notice.

They know you’re studying. And they like it.Do your questions target your weak areas, or just your ego?

Attendings can smell the “I only do cards and pulm because I like them” resident a mile away. Meanwhile, your diabetes and prenatal care notes are a mess. That contradiction? Obvious.

The residents who impress faculty say things like, “I’m realizing I’m weak on outpatient peds, so I’m carving out time to hit that section hard.”

Those are the ones they remember when it comes time for letters.

The Hidden Metric: How You Study On Service

This is where you separate yourself.

Faculty pay far more attention to how you blend Step 3 prep with clinical work than to how much you’re studying. You think you’re being subtle. You are not.

Here’s what we actually notice on the wards and in clinic.

1. The Note-Copying vs. Learning Divide

The worst pattern, and we see it constantly:

Resident is clearly studying, but their notes and clinical reasoning haven’t changed in months.

Boilerplate A/P. Non-specific “monitor” everything. Same vague phrases, day after day.

When we see that, the unspoken conclusion is harsh: “They’re studying for the test, not for the job.”

The residents who stand out do something different. Their notes start reflecting Step 3‑level thinking: risk stratification, next steps, follow-up strategy, explicit contingency plans. That’s when an attending starts thinking, “OK, they actually get what they’re reading.”

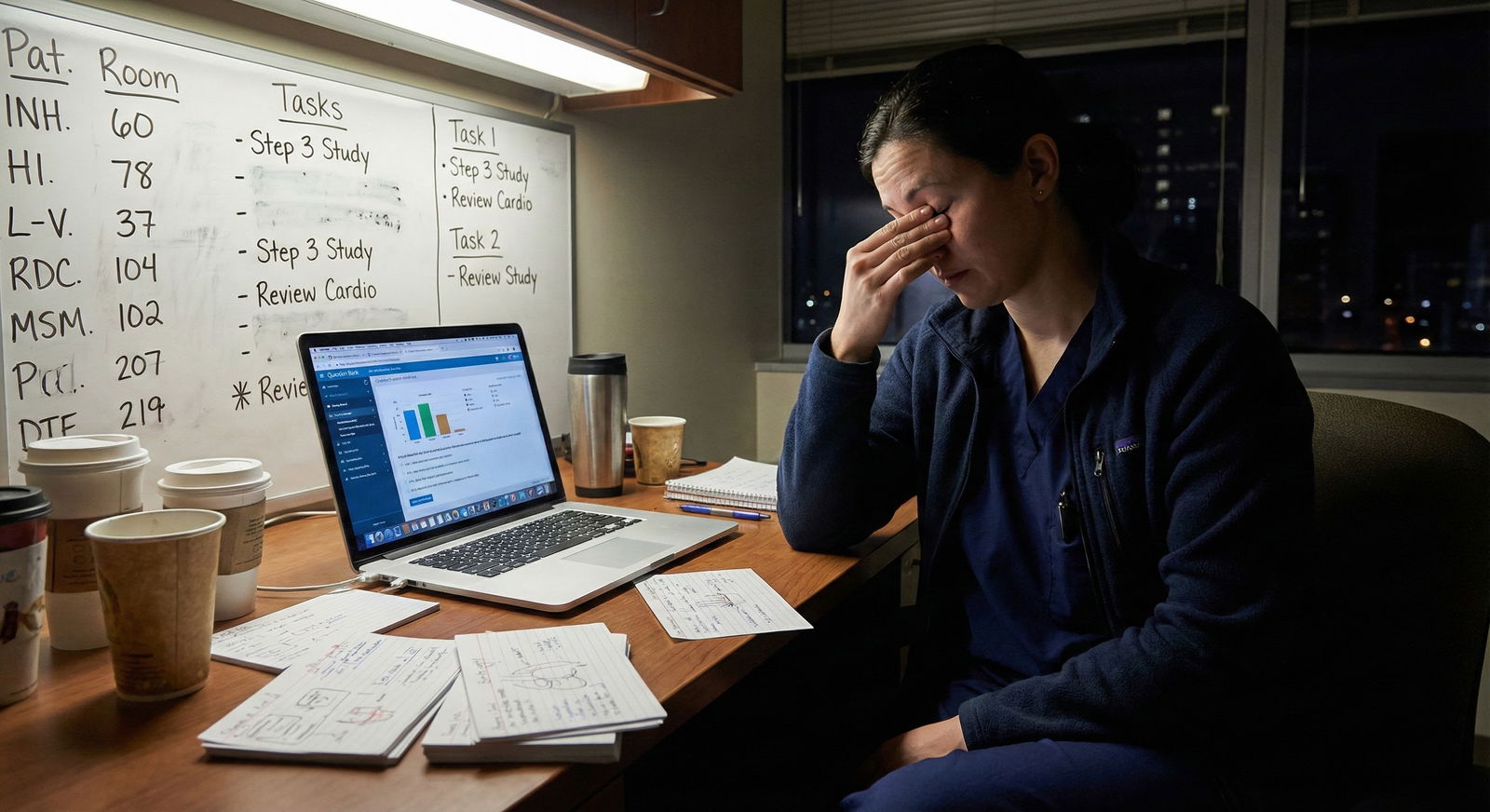

2. How You Use Downtime

Every attending has done the “walk past the call room and see who’s doing what” scan.

Typical scenes:

- One intern asleep at 8 pm with 5 uncalled patients and 2 sick ones.

- One intern doom‑scrolling social media while pages are stacking.

- One intern with lists up, charts open, checking follow‑ups and clicking through UWorld during quiet stretches, but dropping it instantly when a page comes.

Guess which one gets described later as “reliable and committed,” and which gets labeled “questions about prioritization”?

No one expects you to spend every free second studying. Residents are humans. You’re allowed to breathe. But faculty absolutely notice patterns:

If every time we see you you’re “doing a block,” but sign-out is sloppy, follow-up is incomplete, and consults are delayed? That’s not a hardworking image. It’s a misprioritization image.

When residents ask me, “Is it okay if I do questions on call?” my answer is always the same:

“Do excellent clinical work first. If you’re rock-solid, no one will care that you’re studying during slow periods. In fact, they’ll be reassured.”

The Single Biggest Tell: How You Respond to Being Wrong

None of this is theoretical. Faculty are constantly cross-referencing your “I’m studying hard for Step 3” claim with how you handle being wrong in real time.

Here’s the unconscious rubric playing in attendings’ minds:

- You get a management question wrong on rounds.

- How you respond is far more important than what you missed.

There are residents who say, “Ah, I just read about this in UWorld last night. I clearly didn’t frame it right—can we go over why the other choice is better?”

Those people? They get labeled as teachable, reflective, safe. The kind you want to supervise less tightly as they grow.

Then there are the others. The ones who deflect: “Oh yeah, UWorld had a terrible question on this.” Or: “Honestly, Step 3 questions are so unrealistic.”

We remember those comments.

Because Step 3 isn’t just about trivia; it’s about probability, triage, and risk. If you dismiss that entire framework with a lazy “questions are dumb,” it sounds like you’re allergic to systems‑level thinking.

And that’s exactly the kind of thinking we need you to be strongest in as you advance.

What Actually Impresses Faculty About Your Step 3 Habits

Let me spell out what makes attendings quietly think, “This is someone I’d back for a fellowship or chief resident spot.”

It’s not a 260. Most faculty do not even remember their own Step 3 score.

They’re impressed by behaviors that show you’re turning Step 3 prep into better doctoring.

A few examples I’ve literally heard around the workroom:

- “She started Step 3 questions early and brought specific learning gaps to pre‑rounds. That’s unusual for an intern.”

- “He looked up guidelines after that clinic question and updated the note and patient instructions same day.”

- “They built themselves a little daily structure—even on wards—without dropping balls. Very dependable.”

This is what those residents actually do differently:

Study with a clinical anchor.

They do a question block, then immediately think of patients on their list who match those topics. Then they adjust management, notes, or follow-up accordingly. Concrete, not theoretical.Ask pointed, not vague, questions.

Instead of, “How should I study for Step 3?” they ask, “I keep missing questions on peripartum management of hypertension—on L&D, what do you actually want me to know cold?”Align their studying with the rotation.

On nights: emergency, triage, cross‑cover management.

On clinic: outpatient chronic care, screening, prevention.

On wards: inpatient bread-and-butter, disposition, consult criteria.

That alignment makes their growth obvious to anyone paying attention.Build habits, not heroic sprints.

Faculty know the difference between “I’ve been doing 10–20 questions most days” and “I did 400 questions last weekend because my test is in 5 days.” The first one, we trust. The second one, we tolerate.

To visualize the pattern we see across residents:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Steady planners | 30 |

| Last-minute crammers | 40 |

| Chronic delayers | 15 |

| Minimal studiers | 15 |

You want to be in that “steady planners” group. Not because it looks good on a slide, but because those are the people faculty stop worrying about.

The Stuff That Quietly Hurts You (That Nobody Warns You About)

There are a few Step 3 behaviors that faculty will never confront you about directly. But they will absolutely bring them up when your name is on the table.

Let me lift the curtain.

1. Scheduling Step 3 at Clearly terrible Times

- Right after starting a notoriously heavy rotation.

- In the middle of ICU month.

- During an away when you’re trying to impress.

Then you start coming in late, post‑call, foggy, or constantly complaining about being “so behind in UWorld.”

The silent conclusion faculty draw: you do not yet understand workload, boundaries, or how to plan ahead. They worry how you’ll handle real‑life constraints later: family, advanced training, leadership.

2. Making Step 3 Everyone Else’s Problem

This one irritates attendings far more than they’ll admit.

You:

- Push your notes to “finish them later to go study.”

- Offload tasks to co-residents because “my exam’s next week.”

- Ask for last-minute schedule changes repeatedly.

Once? People accommodate you. Everyone remembers what it’s like.

Repeatedly? You get categorized as self-centered.

Residents think faculty are thinking, “But Step 3 is important!”

What they’re actually thinking is: “Everyone here has exams and boards and life. Why is this person asking for special treatment without first proving they can handle their current job?”

3. Publicly Treating Step 3 as a Joke

You’ll hear this on some teams:

- “Lol, Step 3 is a formality.”

- “Nobody fails unless they really tank it.”

- “I’m just going to wing it; it’s not like Step 1.”

Faculty don’t always correct you. But they do clock it.

Because when someone fails Step 3—and yes, it happens more than you think—that same cavalier attitude tends to show up in documentation, patient communication, and follow‑through.

I’ve sat in on meetings where someone’s Step 3 failure is discussed. The exam isn’t the core issue. The recurring pattern of dismissing preparation and overestimating competence is.

How Faculty Actually Want You to Approach Step 3

No one really explains this, so I will.

Attendings want you to treat Step 3 as:

- A forcing function to solidify safe, broad, generalist thinking.

- A chance to close gaps that residency may gloss over.

- A structured way to rehearse “what do I do next” thinking in a low-risk environment.

They do not want you burying yourself in a cave, disappearing from your patients, and re-emerging as a test-taking machine who can’t write a competent discharge summary.

The residents who make the best impression use a simple, boring, relentlessly effective approach:

- Start early enough that you never have to choose between good patient care and studying. Usually early-to-mid PGY1.

- Do manageable, consistent daily work instead of self-destructive marathons.

- Tie every week’s studying to cases you actually see.

- Talk to faculty about content, not about your Qbank score.

Here’s what that roughly looks like over time:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Week 1 | 80 |

| Week 2 | 90 |

| Week 3 | 100 |

| Week 4 | 110 |

| Week 5 | 100 |

| Week 6 | 90 |

| Week 7 | 110 |

| Week 8 | 120 |

| Week 9 | 130 |

| Week 10 | 140 |

| Week 11 | 130 |

| Week 12 | 120 |

Notice: no heroic spike at the end, no flatline until panic-mode. Just sustained, compatible-with-life effort.

Faculty do not need you to follow that exact curve. They just want to see that general pattern: forethought, stability, and integration.

Making Step 3 Prep Work For Your Reputation, Not Against It

Here’s the part almost nobody realizes until too late:

Step 3 is the last standardized exam most of you will ever take. After this, what people think about you is built almost entirely on your daily behavior, your patterns, your reliability.

But Step 3 prep is one of the last times you get a controlled “stress test” in front of faculty. How you handle it becomes a proxy for how you’ll handle bigger, uglier pressures down the line—like boards, fellowship, promotion, and life outside medicine.

Residents who handle Step 3 well send a very clear signal:

- “I can plan ahead.”

- “I can learn efficiently while doing my job.”

- “I turn feedback and study into better patient care.”

- “I do not need constant rescuing or special accommodation.”

Those are the ones faculty remember when someone asks, “Who would you trust to be on call alone?” or “Who should we write a strong letter for?”

If you’re early in the process, use that. Build decent habits now.

If you’re already mid‑trainwreck—cramming, rescheduling, stressed—stop the bleeding. Own it. Ask for real advice. Not “What resource?” but “Given where I am, what would a responsible plan for the next 4–6 weeks look like?”

That kind of honesty plus action? Faculty respect it.

And once Step 3 is behind you, the stakes do not get lower. They get higher. You’ll be managing entire services, cross-covering solo, fielding consults from people who assume you know what you’re doing.

Step 3 is not your final exam. It’s your dress rehearsal.

Treat it like that, and your attendings will notice—for the right reasons.

FAQ

1. Do attendings actually know my Step 3 score?

Often, yes—but not always right away. Some programs formally track it; others only see it when you apply for fellowship, visas, or state licensure. What they’re far more likely to remember, though, is not the number but how you handled the process: whether you passed on the first attempt, whether there was drama around timing, and how your clinical performance looked around that period. A clean pass plus consistently strong performance beats a stellar score with chaos attached to it.

2. Is it bad if I schedule Step 3 during an easier rotation to have more time?

No. Done thoughtfully, that’s exactly what mature planning looks like. The key is not to turn that “easy rotation” into a black hole where your clinical engagement collapses and everything becomes “I’m studying.” If your notes, patient ownership, and day-to-day presence remain solid, most faculty will quietly think, “Smart move.” If you vanish behind UWorld and clinic suffers, the rotation director will remember—for the wrong reasons.

3. How many UWorld questions do faculty expect me to do?

There’s no magic number that impresses anyone. Most faculty don’t track that at all. What they do track is whether your decisions on rounds look like someone who’s seen a lot of cases and thought carefully about them. Finishing the Qbank once, reasonably carefully, and learning from your misses is usually enough. Finishing it twice with no visible change in how you manage pneumonia, chest pain, or prenatal care? That doesn’t impress anyone.

4. I failed Step 3. Am I doomed in my faculty’s eyes?

You’re not doomed. But you are under a microscope for a while. Faculty will look very closely at how you respond: Do you take ownership, build a concrete plan, seek specific help, and keep your clinical work strong? Or do you make excuses and withdraw? I’ve seen residents fail Step 3, recover with a clear, disciplined plan, pass on the second attempt, and still earn strong letters. The failure itself isn’t the end of the story; your response is what gets written into your professional narrative.

With these realities clear, you can treat Step 3 as more than a hurdle. It can be one of the last structured chances to prove—to yourself and to the people training you—that when the pressure rises, you become sharper, not sloppy. The exam will pass. Your reputation is just getting started.