You are sitting on Zoom, halfway through an interview day at what they keep calling a “balanced community-academic program.” The PD just finished saying, “Research is available but not required,” and a chief resident casually mentions “a couple of QI projects every year.”

You exhale. You hate research. You did the bare minimum in med school. This sounds perfect.

Fast forward: it is November of your PGY-1 year. Your inbox has three emails:

- “Reminder: all residents must submit at least one abstract to regional or national meetings.”

- “Please update your scholarly activity tracker by Friday.”

- “Program goal: 80% of residents with at least one peer-reviewed publication by graduation.”

You are staring at them thinking: What did I miss?

This is the mistake: underestimating research expectations at academic programs, especially the “community-academic” hybrids. They sound gentle. They rarely are.

Let me walk you through the warning signs before you lock yourself into the wrong environment for three to seven years.

The Core Problem: “Optional” Research Almost Never Is

At academic programs, research is not decoration. It is currency.

People underestimate this in three common ways:

- Taking “not required” at face value.

- Confusing “no research track” with “no research culture.”

- Assuming community-affiliated = low pressure.

If you remember nothing else: the more a program cares about where grads match for fellowship, the more they care about research. Even if they refuse to say it aloud.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Pure Community | 0.5 |

| Community-Academic | 2 |

| Academic University | 4 |

Rough rule of thumb (per graduate):

- Pure community: maybe 0–1 posters, often QI only

- Community-academic: 1–3 abstracts/posters, 0–1 papers

- University academic: 3–6+ projects, multiple publications or serious attempts

If you apply blind to these differences, you set yourself up for constant guilt, burnout, or worse—being labeled “not engaged” by faculty whose recommendations you will need.

How Academic Is “Academic”? Reading Between the Lines

Programs love vague labels. “Hybrid.” “Community-based with strong academic affiliation.” “Academically oriented community program.”

Those phrases are not neutral. They are signals. Here is how to decode them.

| Signal Type | Pure Community | Community-Academic | Academic University |

|---|---|---|---|

| University name in program title | No | Often | Yes |

| Required scholarly activity | Rare | Common | Universal |

| Fellowship match focus | Minimal | Moderate–High | Very High |

| Protected research time | Rare | Sometimes | Often |

| Publications on website per class | 0–1 | 1–3 | 4+ |

Red-Flag Phrases in Program Materials

Watch for these on websites, in brochures, and during info sessions:

- “Strong scholarly activity culture”

- “Expectation of ongoing resident participation in QI and research”

- “Residents consistently present at national meetings”

- “Dedicated research curriculum and mentored projects”

Translation: you will be pushed to produce something. Often multiple somethings.

On the softer end, but still meaningful:

- “Residents have many opportunities to get involved in research if they choose”

- “Robust mentorship from faculty in various subspecialties”

- “Our residents regularly match at competitive fellowships”

Those three together? That is not an “if you choose” culture. That is a “if you want cards on fellowship, you better have output” culture.

The worst mistake is hearing only the first half: “if they choose,” and tuning out the rest.

Interview Day Warning Signs You Probably Are Ignoring

You will not get a slide that says “WARNING: HIGH RESEARCH EXPECTATIONS.” You have to read the room.

Here is where people get fooled.

1. The “Oh, Just a Few Posters” Casual Comment

You ask a resident, “How much research do people do here?”

They shrug: “Eh, most people do a couple posters, maybe a paper if they care about fellowship.”

Stop. That sentence contains your answer.

- “Most people” = the norm

- “A couple” = more than one

- “Paper if they care about fellowship” = fellowship-bound grads are expected to have something publishable

If you want zero research, this is not your program. Do not convince yourself otherwise.

2. The Program Director Slide Deck

Pay attention to:

- Number of slides showing residents at conferences

- A bullet that says “100% of residents present at regional/national meetings”

- Any mention of ACGME scholarly activity requirements

If they are bragging about resident output, they did not get that by accident. That is culture, not coincidence.

3. “Protected Time” That Is Actually Pressure Time

When a program brags:

- “We provide two weeks of protected research time in PGY-2”

- “Residents can choose one half-day a week for research during electives”

Do not hear “optional vacation.” Hear: We expect you to use this time for something academic.

Protected time exists because there is institutional pressure to generate scholarly output. It is not a gift; it is infrastructure for expectations.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Applicant hears optional research |

| Step 2 | Matches at community academic program |

| Step 3 | PGY1 emails about scholarly activity |

| Step 4 | Chief asks about projects at evaluation |

| Step 5 | Realizes fellowship requires publications |

| Step 6 | Late scramble for projects |

You do not want to live in Box F. Trust me.

The Fellowship Trap: Where Underestimating Research Really Hurts

You can survive three years begrudgingly doing a weak QI poster. You will not thrive trying to get into cards, GI, heme/onc, ortho, derm, ENT, etc. from a research-heavy academic program with a thin CV.

Programs use research as a crude filter. They should not. But they do.

How Academic Programs Quietly Signal Research = Fellowship Currency

Watch what they highlight when discussing fellowship matches:

- “Our residents matched at Mayo, MGH, UCSF, MD Anderson”

- “All our fellowship-bound residents presented work at national meetings”

- “Strong mentorship for scholarly projects to support fellowship applications”

What they are not saying out loud: the residents who did not play that game had a harder time matching.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Low Output | 1,40 |

| Moderate Output | 2,55 |

| High Output | 3,75 |

| Very High Output | 4,85 |

Heavily simplified, but the point stands:

- Low output (maybe 0 posters, no pubs) at an academic program = weak fellowship narrative

- Moderate output (1–2 posters, some QI, maybe a submitted paper) = baseline

- High output = leverage, especially from academic-heavy institutions

If you show up at an academic program expecting that “I can just be a clinician and still do competitive subspecialty,” you are walking into a buzzsaw. Are there exceptions? Of course. They are exceptions.

Tells That a “Community-Academic” Program Is Basically Academic

The hybrid programs are where applicants make the worst assumptions. They see “community” and turn off all their academic radar.

Do not do that.

Strong Warning Signs You Are Effectively in an Academic Culture

If you see any three or more of these, consider the program academically oriented, regardless of the word “community”:

- Direct, formal affiliation with a university medical school

- Multiple on-site fellowships (cards, GI, heme/onc, pulm/crit, NICU, PICU, surgical subspecialties)

- A research director or “Vice Chair of Scholarly Activity” listed on the website

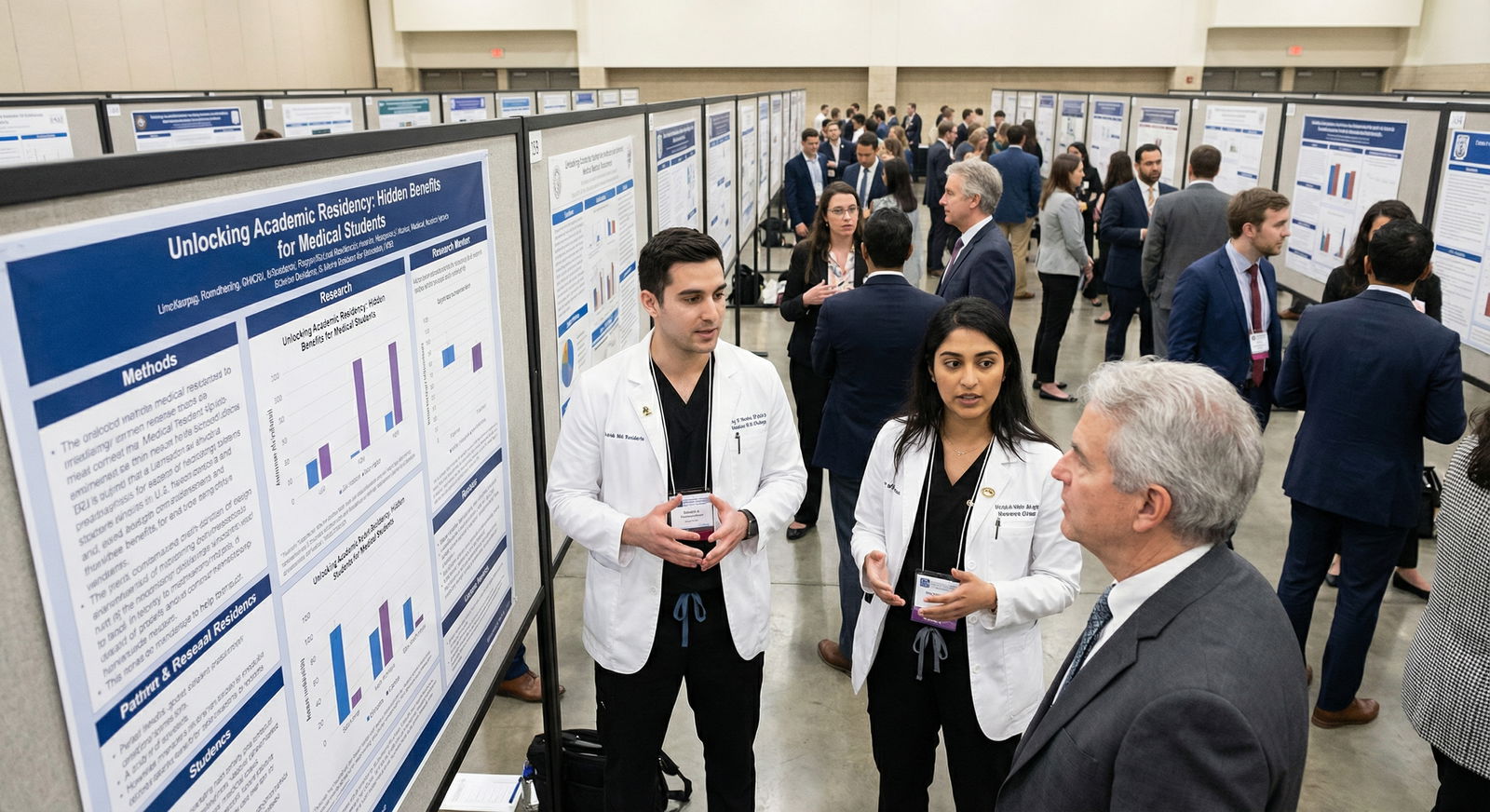

- Annual “Research Day” or “Scholarly Symposium” where residents present

- Required resident scholarly project to graduate, written in the handbook

- PD or APD with a heavy publication record and active grants

- Webpage listing resident publications by year with multiple entries per class

I have seen students match these programs thinking they were “less intense” than university hospitals across town. Then PGY-2 hits and suddenly everyone else is cranking out abstracts and they are drowning in guilt and regret.

Questions You Must Ask on Interview Day (And What Bad Answers Sound Like)

If you want to avoid this mistake, you have to ask direct, slightly uncomfortable questions. And then you have to listen to what people actually say, not what you wish they said.

1. “Is there any required scholarly activity for graduation?”

Bad / concerning answers:

- “We expect everyone to do at least one project by the end of residency.”

- “All residents participate in at least one QI or research project.”

- “Yes, but it is usually easy to meet — at least a poster or presentation.”

That is not low research expectation. That is mandatory research.

Lower-pressure answer looks more like:

- “No formal requirement. Many residents choose to do QI or small projects, but several graduates each year do none and it is not an issue.”

2. “How many residents each year graduate without any posters, presentations, or publications?”

If they cannot name anyone, that is your answer. Research is de facto required.

Watch for:

- “Most of our residents have at least one presentation by graduation.”

- “I am not sure anyone graduates with zero, to be honest.”

Translation: you will be the weird one if you skip it.

3. “If I am not fellowship-bound, would I be at a disadvantage if I chose not to do research?”

Concerning:

- “We would still want you to engage in some scholarly activity.”

- “We encourage everyone to contribute something to our culture of scholarship.”

You are not being hired just to see patients. They want output.

4. “How much of your evaluation or promotion is tied to scholarly activity?”

If faculty say:

- “We comment on engagement in scholarly work in our semiannual reviews.”

- “Research productivity is discussed when writing letters for fellowship or jobs.”

That means your reputation with faculty partially depends on whether you play the research game.

Common Self-Deceptions That Get Applicants Burned

Here is where people lie to themselves. I have watched this play out repeatedly.

“I Will Just Do the Minimum”

At an academic or community-academic program, the “minimum” is not what you think. Minimum usually means:

- One QI project with data collected and presented locally

- One poster at a regional/national meeting

- Maybe participating in someone else’s retrospective chart review

That is still hours of work, coordination, and writing. Done on top of call, notes, and boards. If you are already research-averse, the “minimum” will feel like a chronic, low-grade punishment.

“I Did Fine in Med School Without Research”

You had leverage in med school: strong scores, good letters, personal statement. Research was a bonus in many specialties.

Residency and fellowship are different:

- You are being compared within smaller, more specialized pools.

- At academic programs, almost everyone around you has some output.

Your prior success without research does not translate well into these environments.

“I Will Learn to Like It Once I Start”

Occasionally true. Usually not.

If your med school self did:

- The absolute least required for a scholarly project

- Avoided research electives

- Hated data cleaning, IRB, and writing

Then betting your residency happiness on “maybe my personality fundamentally changes under exhaustion and time pressure” is not a good plan.

How to Sanity-Check Your Fit Before Ranking Programs

You are not trying to avoid all research forever. You are trying to avoid being trapped in an environment that misaligns with who you actually are.

Here is a simple mental checklist.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Do I want a research heavy career? |

| Step 2 | Academic programs fine |

| Step 3 | Accept some QI or small projects? |

| Step 4 | Seek pure community programs |

| Step 5 | Consider light community academic |

| Step 6 | Check true requirements and culture |

Ask yourself:

- Am I okay doing at least one meaningful QI or small research project?

- If no: strongly favor pure community programs.

- Am I okay with being nudged (or pushed) to present at a conference?

- Do I want a highly competitive fellowship from an academic institution?

- If yes: you cannot fully escape research; pick a program with support, not denial.

- When I look at a program’s list of resident publications, do I feel:

- Motivated?

- Indifferent?

- Dread?

If it is dread, stop pretending you are a future physician-scientist.

A Quick Reality Check for Three Common Scenarios

Let me call out three real-world patterns I have seen.

Scenario 1: The “I Just Want to Be a Clinician” Applicant at an Academic Heavy Program

You rank a well-known university program highly because of prestige. You tell everyone, “I just want to be a good generalist.”

What happens:

- You do the bare minimum research.

- Faculty quietly funnel best letters and fellowship opportunities to residents who helped on their projects.

- You graduate clinically fine, academically invisible, and more bitter than you care to admit.

Fix: either accept the academic culture and engage a bit, or pick a strong community program that values clinical work instead of pretending you are in the right place.

Scenario 2: The Fellowship-Bound Student Who Underestimates Early Investment

You want GI, but you match a community-academic program and think: “I will start research in PGY-2 or PGY-3.”

What happens:

- PGY-1: you are swamped, you postpone.

- PGY-2: you scramble for last-minute projects; timelines do not match fellowship app cycle.

- PGY-3: much of your “work” is still unpublished, weakly presented, or barely started.

You then look at co-residents who started early and realize your application is much thinner.

Fix: if you want fellowship from an academic or community-academic program, accept research expectations up front and get involved early. Or consciously choose a low-research path and understand it may limit certain subspecialties.

Scenario 3: The Burnt-Out Resident Who Thought QI “Does Not Count”

Some people think “at least it is QI, not real research.” Then they discover:

- QI still needs data collection, analysis, sometimes IRB exemption, write-ups.

- Program leadership still judges you on whether you “engaged meaningfully.”

So they end up overcommitting, under-delivering, and constantly apologizing for slow progress. It becomes another source of shame.

Fix: be honest during interviews about what scholarly output actually costs you in time and energy. Do not treat QI as magically free work.

FAQs

1. How can I tell from the website alone if research expectations are high?

Look for three things:

- A dedicated “Resident Scholarly Activity” or “Research” page with lots of recent entries.

- Photos of residents repeatedly at national conferences (ACP, ATS, ASCO, DDW, etc.).

- Language like “Residents are expected to…” or “All residents participate in…” regarding projects.

If you see multiple years of posters and publications listed per class, assume research is structurally expected, not optional.

2. Is it a mistake to avoid all academic programs if I dislike research?

Not necessarily, but be precise. Avoiding university programs because you hate research is rational. Avoiding every community-academic program without looking closer can hurt you if you also want strong clinical training or certain fellowships. The real mistake is ranking a research-heavy place highly while telling yourself “I will just say no to research.” You probably will not, and they probably will not quietly accept that.

3. Can I still match a competitive fellowship from a low-research community program?

Yes, but the path is narrower and more dependent on outstanding clinical performance, strong letters, and sometimes away rotations or external networking. You will likely have fewer built-in research options, so your application has to be strong elsewhere. The bigger mistake is choosing a low-research community program and expecting it to magically produce an R01-level CV. It will not.

4. If I realize late that my program’s research expectations are too high for me, what can I do?

Three practical steps:

- First, narrow your obligations. Drop unnecessary side projects and stick with one manageable QI or small study that can realistically be completed.

- Second, be honest with a trusted mentor or chief: “I am struggling with the research culture here and need help setting limits while still meeting graduation requirements.”

- Third, for fellowship or job plans, lean hard on your clinical strengths and be transparent in interviews rather than fabricating enthusiasm for research. The mistake would be silently drowning in projects for three years instead of strategically meeting the minimum and protecting your sanity.

Key Takeaways

- “Optional research” at academic and community-academic programs is rarely truly optional; culture and fellowship goals turn it into expectation.

- You must actively look for warning signs—website language, resident output, required scholarly projects, and interview answers—rather than assuming “community-affiliated” means low research pressure.

- Match your actual tolerance for research with the program’s true culture, not its marketing language, or you will spend residency fighting the system instead of growing in it.