If you want cards or GI and you are not treating preclinical research like a second major, you are already behind your competition.

Cardiology and gastroenterology fellowships are blood sport. The people matching them did not “dabble” in research. They built a 4–6 year arc that starts before M1 and peaks in early PGY2. At every point, they knew what they were doing and why.

I am going to walk you through that arc. Month by month in preclinical. Then semester by semester in clinical. Then through residency milestones. You will see exactly when to be doing what if you want to be a realistic candidate for a competitive cardiology or GI fellowship.

Big Picture: Your 7–8 Year Research Arc

Before we zoom into preclinical, you need the macro-frame.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Pre-med / M0 - 6–12 months | Initial exposure, basic data work |

| M1–M2 - Longitudinal projects | Retrospectives, QI, case reports |

| M1–M2 - First authorships | Try to land at least 1–2 |

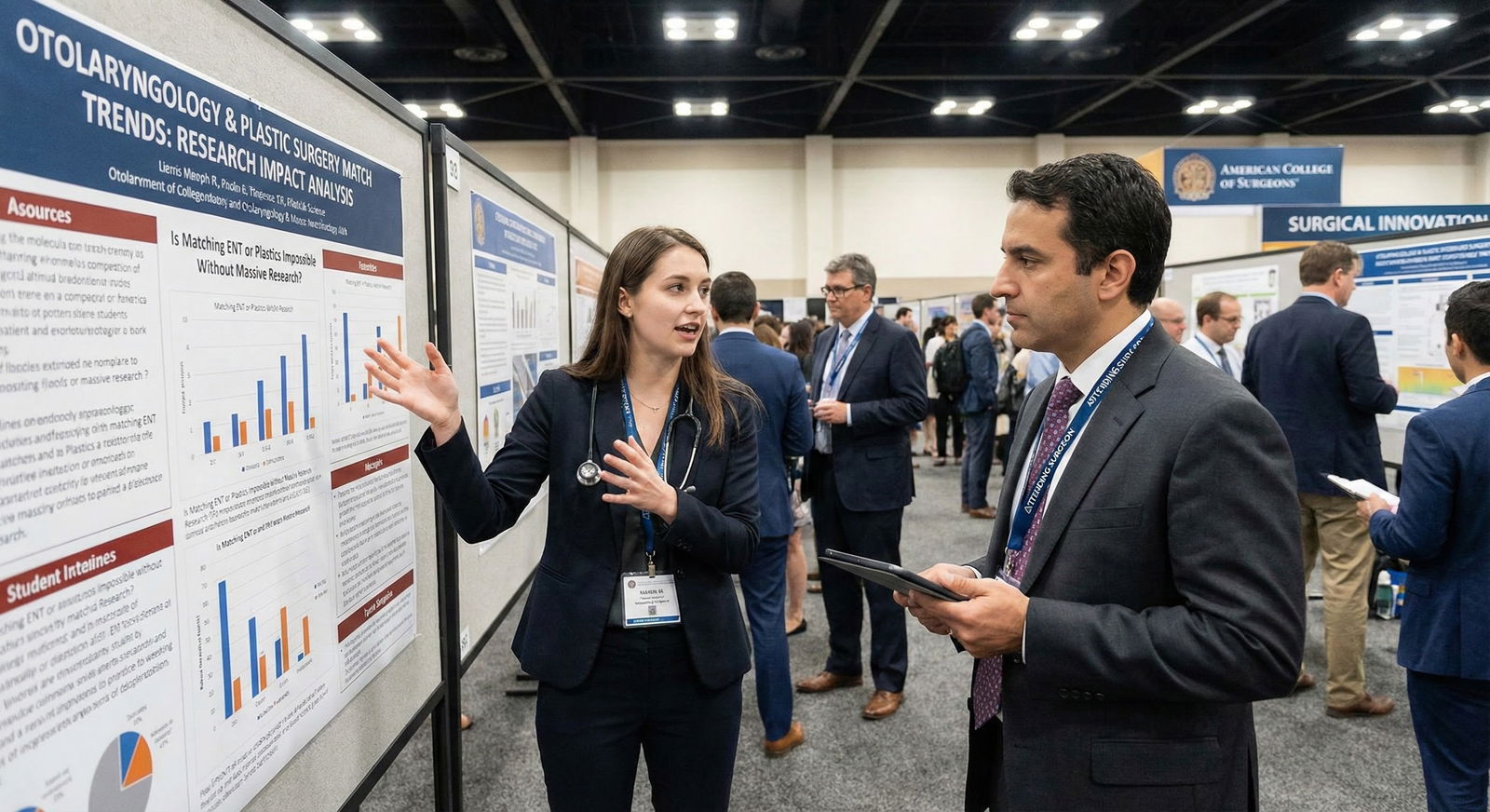

| M3–M4 - Clinical tie-in | Cards / GI electives, abstracts, posters |

| M3–M4 - Residency apps | Leverage mentors and output |

| PGY1 - Foundation year | Limited but targeted projects, get on teams |

| PGY2–PGY3 - Heavy lift | Grants, multi-project portfolio, high-yield pubs |

| PGY2–PGY3 - Fellowship apps | Submit with a coherent story |

The harsh truth: fellowship selection committees for cards and GI like:

- Multiple first- or co-first-author publications

- A clear, consistent interest (not “oh I suddenly love cardiology as PGY2”)

- Letters from recognizable names in the field

- Evidence you can start and finish projects under pressure

That starts now, not “later when things calm down” (they do not).

Pre-Matriculation (M0): 6–12 Months Before M1

At this point you should not be chasing prestige. You should be chasing basic skills and proof you can complete work.

Goals for this phase (minimum):

- 1–2 ongoing projects before M1 starts

- Familiarity with basic data tools (Excel, maybe R or SPSS)

- One potential longitudinal mentor in cardiology or GI or general internal medicine with ties to those divisions

Timeline:

6–9 months before M1

You should:

- Email 5–10 faculty in:

- Cardiology

- GI / hepatology

- General internal medicine with cardiac or GI research

- Ask specifically for:

- Retrospective chart review projects

- Registry or database projects

- Simple QI projects related to heart failure clinics, endoscopy wait times, etc.

Bad email: “Hi, I am interested in cardiology, I’d like to do research.”

Better email: “I am an incoming MS1 with strong interest in cardiology and population outcomes. I can commit 5–7 hrs/wk for at least 12 months. I am particularly interested in heart failure readmission or AFib management projects. Do you have any ongoing retrospective or QI projects where I could help with data collection and analysis?”

At this point you should not care if you are 5th author. You are buying entry into a lab or division.

Targets by the time M1 starts:

- At least 1 project where:

- IRB is already approved

- Data collection can be started with minimal training

- You have:

- Met the PI at least once (Zoom or in person)

- Clarified expectations and authorship possibilities

M1: Semester-by-Semester, Month-by-Month

Your classmates will talk about “adjusting to med school” for a year. You do not have that luxury if you want cards or GI at a top program. You need a sustainable, not insane, research load.

M1 Fall (Aug–Dec)

Primary focus: Learn how to be a medical student.

Secondary focus: Keep at least one project moving forward.

At this point you should:

- Commit 3–5 hours per week to research, consistently

- Have:

- A concrete role (e.g., chart abstraction for AF readmissions, colonoscopy quality measures)

- A biweekly or monthly check-in with your team

Month-by-month:

August–September (first 8 weeks)

You should:

- Spend most time learning:

- How to study for your curriculum

- What exam style your school uses

- For research:

- Do basic onboarding: IRB training, HIPAA modules

- Shadow your mentor in clinic once or twice if possible (cards clinic, endoscopy day)

October–November

You should:

- Be in the data collection or early analysis phase on one project

- Start pushing for:

- Definition of endpoints

- Timelines for abstract submission (e.g., ACC, AHA, DDW, ACG)

December

You should:

- Ask your mentor:

- “What conferences in the spring/summer could we realistically target?”

- Aim for:

- One abstract drafted over winter break, even if rough

M1 Spring (Jan–May)

This is where the serious people start separating themselves.

At this point you should:

- Be materially contributing to at least one project

- Be listed on one abstract submission in progress or very close

Month-by-month:

January–February

- Take on slightly more (4–6 hrs/week) research time once you know how to study

- Start learning:

- Basic stats (read methods sections, ask the fellow or senior resident to explain)

- How to structure an abstract and intro section

March–April

You should be:

- Finishing data collection on one project

- Drafting:

- Abstract for conference

- First-pass manuscript outline (even if it gets heavily edited later)

May (end of M1)

By now you should have:

- 1 abstract submitted or ready to submit

- Ongoing work on at least 1 additional project (e.g., case series, QI, or another retrospective)

If you have nothing tangible by the end of M1, you are not doomed. But you are now on an accelerated timeline and need a big M2.

M1 Summer: 8–12 Weeks of Focused Research

This is your first major inflection point. Waste this, and you will chase your tail for years.

At this point you should:

- Treat the summer as a full-time research block (35–40 hrs/week)

- Have 1–2 clearly scoped projects with realistic finish lines

Ideal setup:

(See also: how away rotations actually work in hyper-competitive specialties for more.)

- Funded research fellowship or scholarship (AHA summer research, institutional research program, etc.)

- Formal deliverables: abstract, poster, and a manuscript draft

| Output Type | Minimum Goal | Strong Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Abstracts | 1 | 2–3 |

| Posters | 1 | 2 |

| Manuscripts (submitted) | 0–1 | 1 |

| New mentors | 1 | 2 |

Week-by-week (rough):

- Weeks 1–2: Deep dive into background, refine question, lock analytic plan

- Weeks 3–6: Intense data work, running analyses, meeting weekly with mentor

- Weeks 7–8: Abstract writing, poster prep, manuscript drafting

If possible, align your work with major meetings:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| ACC | 10 |

| AHA | 7 |

| DDW | 8 |

| ACG | 6 |

(Values = rough months before meeting abstracts are due. Translation: you need usable data months ahead.)

M2: Scaling and Positioning Before Clinical Years

M2 is where you convert “I helped on some projects” into “I have a portfolio that looks like someone who is actually heading for cards or GI.”

M2 Fall (Aug–Dec)

At this point you should:

- Have at least one abstract accepted or under review

- Be an author on at least one submitted or nearly-submitted manuscript

You are also now studying for Step 1 (or equivalent). That matters.

Non-negotiable rule: Step score (or strong pass) beats incremental research. If your exam prep is in trouble, you pause new research intake and maintain only existing commitments.

But assuming you are stable:

- 3–5 hrs/week on:

- Finalizing manuscripts from M1 summer

- Starting 1 larger, more sophisticated project (multi-year cohort, meta-analysis, etc.)

M2 Spring (Jan–May)

You are balancing:

- Dedicated board prep

- Existing projects that are nearing completion

- Identifying where you will do third-year rotations and potential elective time in cards/GI

At this point you should:

- Be lined up to present at at least one conference during M2–M3

- Have at least 1–2 first- or co-first-author manuscripts submitted or in final draft

End of Preclinical: What “On Track” Looks Like

If you are “on track” by the end of M2, your research CV will roughly look like this:

- 2–4 abstracts (at least some in cardiology or GI or related IM fields)

- 1–3 publications (they do not all need to be in top-tier journals)

- Evidence of continuity: same mentor or same theme across several projects

- A clear story of interest: heart failure, arrhythmias, interventional, IBD, liver, advanced endoscopy, etc.

If you are aiming for a powerhouse fellowship (MGH, Penn, Duke, Mayo, etc.), you want to be on the upper end of that range.

M3–M4: Clinical Years as Research Leverage

You asked about preclinical, but preclinical only matters if it positions you well here. So I will keep it concise but specific.

M3 Year

At this point you should:

- Use IM and surgery rotations to:

- Identify faculty who are fellowship program directors or research heavyweights in cards/GI

- Attach yourself to case reports, small series, and ongoing trials

During IM rotation:

- Perform well clinically first. You need honors and strong comments.

- Quietly signal interest: “I have been doing retrospective work in heart failure and would love to stay involved with research during M3–M4 if there are ongoing projects.”

Ideal outputs by end of M3:

- 1–2 new clinical projects started (often faster turnaround than pure preclinical data projects)

- 1 additional abstract and/or poster accepted based on M1–M2 work

- At least one strong letter-writer brewing in IM, cards, or GI

M4 Year

You are now applying for internal medicine residency.

At this point you should:

- Have your research consolidated into a coherent narrative:

- “I have spent the last 4 years working on outcomes in heart failure hospitalizations and AFib management, leading to X abstracts and Y publications…”

- Aim for:

- 4–8 total publications and abstracts combined by the time ERAS goes in for residency (more is obviously better for top cards/GI paths, but quality and coherence matter)

You also use M4 electives:

- Cards inpatient consult, CCU

- GI / hepatology elective

to cement relationships and maybe squeeze in a fast-turnaround project.

Residency: The Fellowship-Defining Window

The committees care far more about what you do in residency than as a medical student. Preclinical work is a foundation and a signal. Residency work is the main argument.

PGY1 (Intern Year)

At this point you should:

- Survive intern year, yes.

- But also:

- Open communication early with cards and GI faculty at your program

- Join 1–2 ongoing projects that are realistic for an intern schedule

Strategy:

- Focus on:

- Cases and small retrospective projects with quick turnaround

- Joining an existing lab group meeting every 2–4 weeks

Output goals by the end of PGY1:

- 1–2 additional abstracts / posters

- 1–2 manuscripts where you are first or second author, in progress if not submitted

PGY2–PGY3: Peak Productivity and Application Window

This is where your early start pays off.

At this point you should:

- Have a clear niche:

- Structural heart, EP, preventive, advanced imaging, IBD, liver transplant, advanced endoscopy, etc.

- Be a key player on:

- 2–4 active projects at any time, staggered in their lifecycle

Fellowship applications (cards as PGY2, GI usually PGY2–PGY3) will look closely at:

- Number and quality of your publications (especially in last 2–3 years)

- Letters from recognizable cardiology/GI figures who can say:

- “This resident has been working with me since M1/M2 on multiple projects…”

If you did the preclinical work right, those letters write themselves because you have a years-long relationship.

Common Pitfalls and How Preclinical Planning Avoids Them

Starting too late

- Reality: Many successful cards/GI applicants first touch research in PGY1. They just work twice as hard.

- Fix: Preclinical research gives you a cushion so every resident-year output builds on prior work instead of starting from zero.

Random, scattered projects

- Preclinical risk: Jumping on derm, ortho, peds projects “just because.”

- Better: 70–80 percent of your serious work should be in IM-cards-GI adjacent territory by end of M2.

Overcommitting during boards and clerkships

- Rule: Protect Step and core clerkship performance. Pause new projects during these peaks and focus on wrapping old ones.

No mentor continuity

- Goal: By end of M2, you want at least one PI who knows you as “their” student and is likely to pick you up again in residency if you end up at the same place.

Quick Reference: Preclinical Research Targets for Future Cards/GI

| Time Point | Minimum Target | Competitive Target |

|---|---|---|

| Start of M1 | 1 ongoing project | 2 projects + identified mentor |

| End of M1 | 1 abstract submitted | 1 abstract + 1 paper in draft |

| End of M1 Summer | 1 poster or abstract | 2–3 abstracts + 1 manuscript draft |

| End of M2 | 1 publication + 2 abstracts total | 2–3 publications + 3–5 abstracts total |

FAQ (Exactly 4 Questions)

1. Do I absolutely need publications before residency to match a good cardiology or GI fellowship later?

No, but they help a lot. Residents who match top cards or GI fellowships from strong IM programs often enter residency with at least a few abstracts and 1–3 publications. It shows you can finish projects and makes it much easier to ramp up in PGY1–2. If you arrive with zero, you can still match, but you will have to be very productive, very fast during residency.

2. How much does the journal impact factor matter for preclinical research?

Less than students think. During preclinical years, quantity and completion matter more than chasing high-impact journals. A string of solid publications in mid-tier specialty journals (e.g., American Journal of Cardiology, Digestive Diseases and Sciences) plus consistent abstracts at AHA/ACC or DDW/ACG will impress people more than one lucky “big” paper surrounded by nothing. Your fellowship letters will contextualize the quality for the committee.

3. What if my school has weak cardiology or GI research?

Then you get creative. Look for: virtual collaborations, multi-center registries, national trainee research networks, and remote work with larger academic centers (many cardiology and GI groups are used to remote students doing chart review and data work). Also, internal medicine outcomes, epidemiology, or QI with cardiac or GI endpoints can still be very valuable. You are building skills and a narrative, not just chasing logos.

4. How do I balance research with Step studying and not burn out?

You time-box aggressively. During the heaviest studies (dedicated Step 1, Step 2, and your hardest clerkships), you switch to a “maintenance mode”: 1–2 hours per week maximum, only for projects that are close to submission or that would collapse without minimal input. The rest of the year, you run 3–6 consistent hours per week. Burnout comes from thrashing—starting and dropping projects—more than from steady, modest commitment.

Key points:

- Preclinical years are not about prestige; they are about building a consistent research habit and a coherent story tied to cardiology or GI.

- By the end of M2, you want tangible output (abstracts, manuscripts) and at least one mentor who can follow your trajectory into residency and beyond.

- The real fellowship leverage happens in residency, but the residents who win that game usually started this timeline back in M1—while everyone else was “adjusting.”