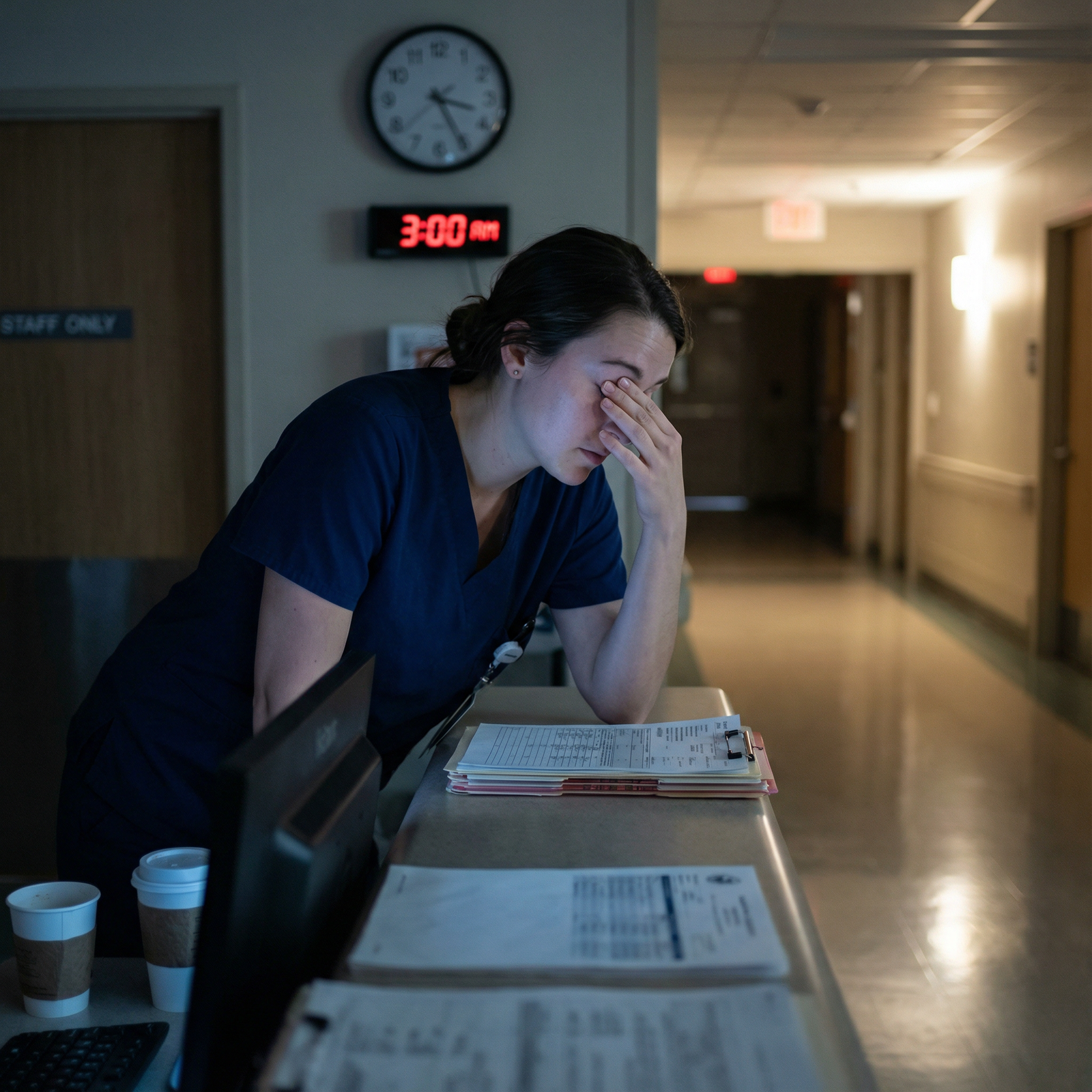

The way most residents nap on night float is wrong. Not suboptimal. Wrong.

They treat sleep like an optional side quest instead of the entire foundation of not hurting people on rounds at 7 a.m. And the biggest damage does not happen at 3 a.m. on shift. It happens in that “little nap” you take at 4 p.m. or the “I’ll just lie down for 20 minutes” after sign-out.

You want to survive night float without wrecking your brain, your mood, or your relationships? Then you must stop making the same nap mistakes almost every resident makes.

Let me walk you through the traps.

1. Treating “Naps” Like Full Nights of Sleep

The most common error: turning your “nap” into a full-on sleep cycle.

Day after your first night shift, you get home at 9 a.m., crash, and wake up at 5 p.m. You think you are rested. You are not. You just killed your night.

You have to decide: are you doing a true nap or a core sleep block?

On continuous night float (5–7 nights in a row), you generally need:

- One long anchor sleep (3–6 hours) in the late morning or midday, and

- One short nap (60–90 minutes) in the evening before shift.

Residents butcher this by “accidentally” sleeping 7 hours straight in the middle of the day, then lying awake, wired, from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. on call.

Here is what the structure should look like for a typical 7 p.m.–7 a.m. night float:

| Block Type | Typical Time | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Post-shift core sleep | 9 a.m.–1 p.m. | 4 hours |

| Second sleep / nap | 3 p.m.–5 p.m. | 2 hours |

| Pre-shift power nap | 6 p.m.–6:30 p.m. | 20–30 min |

Where residents screw it up:

- Sleeping from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. “because I was so tired.”

- Taking a 3-hour “nap” from 7–10 p.m. and waking up jet-lagged at the start of shift.

- Skipping the pre-shift nap completely, then falling apart at 4 a.m.

If you are on continuous nights, your “nap” is not optional fluff. It is a carefully timed extension of your core sleep. Overshoot it and you destroy your circadian timing. Undershoot it and you hit a wall at 3 a.m.

2. Napping at the Wrong Time in the 24-Hour Cycle

You can nap at 4 p.m. or at 11 a.m. and feel completely different. Same minutes, different brain.

Circadian biology does not care that you are a resident. Your internal clock still expects:

- Deepest sleep drive: 2–6 a.m.

- Secondary slump: 1–4 p.m.

If you nap at 7 or 8 p.m. on a night you work 7 p.m.–7 a.m., you are fighting your “wake” window and teaching your brain to be sleepy when you need to be sharp. Residents do this when they go home post-call and “just lie down for a bit” around 6 p.m. That “bit” often becomes a 4-hour crash that destroys the next night.

The usual bad pattern I see:

- Sleep post-shift from 9 a.m.–2 p.m.

- Feel groggy, caffeinate heavily.

- Around 7 p.m. before shift, feel wiped and lie down “just for 20 minutes.”

- Wake up disoriented at 9 p.m. when cross-cover is blowing up your phone.

You just created sleep inertia at the exact time you need to be functional.

A safer pattern:

- Major sleep block ending by ~4–5 p.m.

- Short pre-shift nap ending at least 30 minutes before you have to be “on.”

If you are going to nap:

- Aim for early afternoon (1–4 p.m.) for your longer block.

- Use a brief power nap (20–30 minutes) 60–90 minutes before shift.

Stop doing two-hour “naps” starting at 6 p.m. That is not a nap. That is self-imposed jet lag.

3. Ignoring Sleep Inertia: The “Wake Up Five Minutes Before Sign-Out” Disaster

Sleep inertia is the foggy, “where am I?” brain that hits you right after waking up, especially from deep sleep. And it can last 30–60 minutes.

Residents routinely set an alarm for 6:50 p.m. with a 7 p.m. start. Then they wonder why they feel drunk until 9 p.m.

Bad idea.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| 10–20 min | 20 |

| 30–45 min | 40 |

| 60–90 min | 80 |

| 120+ min | 90 |

Relative misery score, not exact science, but directionally accurate.

Mistakes I see constantly:

- Rolling into sign-out 5 minutes after waking up, still in REM brain.

- Taking a 90-minute nap ending at 2 a.m. and then trying to manage a crashing patient at 2:10 a.m.

- Setting alarms without any buffer to “reboot” before clinical decisions.

Better pattern:

- If you take a short power nap (10–20 minutes): you can be mostly functional after 10–15 minutes.

- If you take a full-cycle nap (60–90 minutes): give yourself 30–45 minutes of low-stakes activity before handling anything critical.

So do not:

- End a 90-minute nap at 6:55 p.m. with cross-cover sign-out at 7 p.m.

- Wake up from a deep nap and immediately rewrite TPN orders.

Plan buffer time: shower, walk, light snack, chart review. Your brain is not a light switch.

4. Using Caffeine Like a Sledgehammer Instead of a Scalpel

Caffeine is not the enemy. Stupid caffeine timing is.

Night float residents often:

- Slam a large coffee at 10 p.m.

- Chase it with an energy drink at 2 a.m. “to get through the last few hours.”

- Wonder why they are staring at the ceiling at 10 a.m. when they desperately need sleep.

Your naps are useless if your system is still saturated with caffeine.

Here is the mistake pattern:

- No caffeine early in the night when it could help.

- Massive doses after midnight.

- Delayed sleep onset by 1–3 hours post-shift.

- Shortened and fragmented daytime sleep.

- Then “fix” with more caffeine the next night.

You are building a cycle that turns night float into something that looks suspiciously like chronic insomnia.

More intelligent rules:

- Use a moderate dose (e.g., 100–200 mg) early in the shift (around 7–9 p.m.).

- A small maintenance dose (50–100 mg) around midnight if needed.

- Hard stop on caffeine by 2–3 a.m. so it is wearing off when you get home.

Bad combinations with naps:

- Chugging coffee immediately before a 90-minute nap. You wake up anxious and wired, not rested.

- Using “caffeine naps” (drink coffee then nap 20 minutes) but oversleeping the alarm and waking up in the worst of both worlds: mid-REM plus peak caffeine.

Caffeine naps can work if you have discipline and a timer. Most residents do not on night 5 of 7.

5. Pretending the Call Room Is a Sleep Environment

I have watched residents “nap” in a call room with:

- Fluorescent hallway light streaming under the door.

- Pager on loud on the pillow.

- Overhead light on “so I don’t oversleep.”

- Colleague dictating notes at the same desk three feet away.

Then they say, “Naps don’t help me. I just feel worse.”

Of course they do.

On night float you are not going to get spa-level conditions. But you can avoid sabotaging yourself.

Stop making these basic environmental mistakes:

- No eye mask, trying to nap with overhead lights or hallway light.

- No earplugs or white noise, so every door slam wakes you.

- Keeping your phone face up and on sound, lighting up your whole visual field with each notification.

- Lying there, “resting”, while scrolling Epic messages or Instagram.

At minimum for any nap over 20 minutes:

- Dark as you can get it: eye mask if needed.

- Consistent noise level: fan app, white noise, or actual fan.

- Devices on Do Not Disturb, with only true emergencies allowed through.

If you cannot truly control the call room, shorten your expectations. Use 10–20 minute power naps to blunt sleepiness instead of expecting full deep sleep you will not actually protect.

6. Trying to “Catch Up” with Monster Sleeps on Days Off

Another big night float myth: “I will just catch up on my days off.”

Here is what usually happens:

- You finish your last night.

- Decide to “crash and reset” with a huge daytime sleep: 8 or 10 hours.

- Wake up at 8 p.m., feeling like you live on Mars.

- Stare at the ceiling until 4 a.m., then sleep until noon.

- Show up to your next day shift half-adjusted, half-destroyed.

You cannot fully erase chronic sleep debt in one or two mega-sleeps. And trying usually wrecks your transition back to days.

Better:

- Accept you are going to be partially tired.

- Limit post-night sleep on your last shift to 3–5 hours.

- Get up in the early afternoon, go outside, use bright light, move.

- Go to bed that night at a reasonable “day schedule” time (9–11 p.m.), aiming for a full 7–9 hours.

The mistake is letting guilt or exhaustion make you sleep until dinner on your “off” day. That is not recovery. That is extending night shift jet lag.

7. Napping “Just When I Feel Like It” – No Plan, No Structure

I hear this from residents all the time: “I just nap when I am tired.” That is a recipe for fragmented, useless sleep.

Unplanned naps cause:

- Random 90-minute crashes at 5 p.m.

- Micro-naps sitting at the computer at 3 a.m. while entering orders.

- Inconsistent sleep windows your brain never adapts to.

Your brain likes patterns. Even on nights.

A simple, protective structure for a 7-p.m.–7-a.m. rotation:

- Post-shift sleep: 9 a.m.–1 p.m. (set alarm).

- Optional second block: 3–5 p.m. (set alarm, not negotiable).

- Pre-shift power nap: 6–6:20 p.m. on really rough weeks.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | End Shift 7 a.m. |

| Step 2 | Home 8-9 a.m. |

| Step 3 | Core Sleep 9 a.m.-1 p.m. |

| Step 4 | Wake and Light Exposure |

| Step 5 | Second Block 3-5 p.m. |

| Step 6 | Quiet Wake 3-5 p.m. |

| Step 7 | Short Pre-shift Nap 6-6 -20 p.m. |

| Step 8 | Start Shift 7 p.m. |

| Step 9 | Still exhausted? |

You can modify the exact times, but you need a plan. Not vibes.

8. Napping Too Long on Post-Night “Post-Call” Days

This one is sneaky. On non-float services, when you are post-call after a 24-hour shift, there is a temptation to just sleep “until I wake up.” That approach, if you have another day shift the next day, is terrible.

Common mistake:

- On a normal admitting day – on call until 7 a.m.

- Go home, sleep from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.

- Now wide awake until 2–3 a.m.

- Up again at 6 a.m. for regular day shift.

You have just compressed your “night” into 3 hours. Your next work day will be a mess.

Better limit post-call daytime sleep to 4–6 hours max if you must be awake early the next day. Yes, you will be tired that evening. That is the point. You want enough sleep pressure to get to bed at something like 9–10 p.m. and start reclaiming a human schedule.

Do not try to be “heroic” by pushing through without any post-call sleep. That is how people crash cars driving home. But do not let a 9-hour daytime nap poison the next 2–3 days either.

9. Using Screens as a Sedative After Shift

Another recurring issue: coming home from night float, climbing into bed “to nap,” then picking up your phone. One podcast, one YouTube video, three Instagram reels. Suddenly it is 11 a.m., the sun is bright, and you have now delayed the start of your main sleep block.

The bad pattern:

- “I need to decompress” → 60–90 minutes of bright blue light.

- Sleep onset delayed.

- Sleep window squeezed to 3–4 hours instead of 5–6.

- Afternoon crash so bad you take an unplanned long nap.

- Night shift brain more broken.

Your brain is already confused about what time it is. Dumping bright light plus stimulating content on it right before your “night” (daytime sleep) makes that worse.

You do not have to live like a monk. But:

- Put a time limit on screen decompression (e.g., 20–30 minutes).

- Use blue-light filters or glasses if you are very sensitive.

- Prefer audio-only content while you are already in a dark room ready to sleep.

The error is scrolling yourself straight through the best window for daytime sleep, then complaining that “I just can’t sleep during the day.”

10. Underestimating How Much Sleep You Actually Need

Last point, and it is brutal: most residents underestimate how much sleep they require to maintain safe performance on nights.

You cannot run safely on 3–4 hours per 24 for 7–10 days straight. You might survive. You will not perform well.

Typical adult need is around 7–9 hours in 24 hours. On nights, you will rarely get that in one block. So you should be aiming for:

- Total: At least 6–7 hours in 24, via a core block + nap(s).

Too many residents accept 4–5 hours total as “just what residency is.” Then they:

- Miss subtle exam findings at 4 a.m.

- Forget to renew heparin prophylaxis.

- Discharge patients without pending culture review.

You do not get bonus points for suffering. You just become dangerous.

Here is what your total sleep often really looks like, if you are not careful:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Night 1 | 6.5 |

| Night 3 | 5.5 |

| Night 5 | 4.5 |

| Night 7 | 4 |

You start somewhat reasonable, then erode into chronic sleep debt. The “I feel okay” you tell yourself on night 7 is not a reliable metric. Cognitive performance often drops long before you feel as sleepy as you actually are.

FAQs

1. Is a 3-hour nap better or worse than a 90-minute nap between night shifts?

Three hours usually means you are going through about two full sleep cycles. That can be fine if it is part of your planned total (e.g., 4 hours post-shift plus a 3-hour “nap” later). The mistake is dropping an unplanned 3-hour nap at the wrong time, like 6–9 p.m. before a night shift. If you are within 3 hours of the start of your shift, shorter is safer: 20–30 minutes or a full 90 minutes, with buffer time for inertia.

2. What if I truly cannot sleep during the day even when tired?

The typical errors: using caffeine too late, too much light exposure after shift, and no real wind-down routine. Fix those first. If you still cannot maintain at least a 3–4-hour block of daytime sleep despite strict sleep hygiene and strategic naps, you should talk to a physician. Chronic insomnia, anxiety, or sleep disorders do exist in residents, and they are often ignored until burnout hits hard.

3. Is it ever okay to stay up after a night shift to “flip back” to days?

Yes, but only in very specific situations: usually after your last night, when you are transitioning back to days and do not have patient care that same day. Even then, a short 2–3-hour morning nap is safer than pushing through completely. The mistake is trying to use total sleep deprivation as a “reset button” when you still have more nights to work. That will just compound your fatigue and degrade your performance.

You want the short version?

- Stop pretending naps are random. Time them with a plan: core sleep block plus carefully chosen short naps.

- Protect the basics: darkness, quiet, caffeine cutoffs, and buffer time after waking before making clinical decisions.

- Respect your total sleep need across 24 hours. You cannot safely compress real human biology into a heroic residency story.