The way most older premeds explain their career pivot to medicine is sabotaging them more than their GPA or MCAT ever will.

You do not lose people because you are 32, or 38, or 45. You lose them because your story makes them nervous. Confused. Or bored. The age is not the problem. The way you talk about it is.

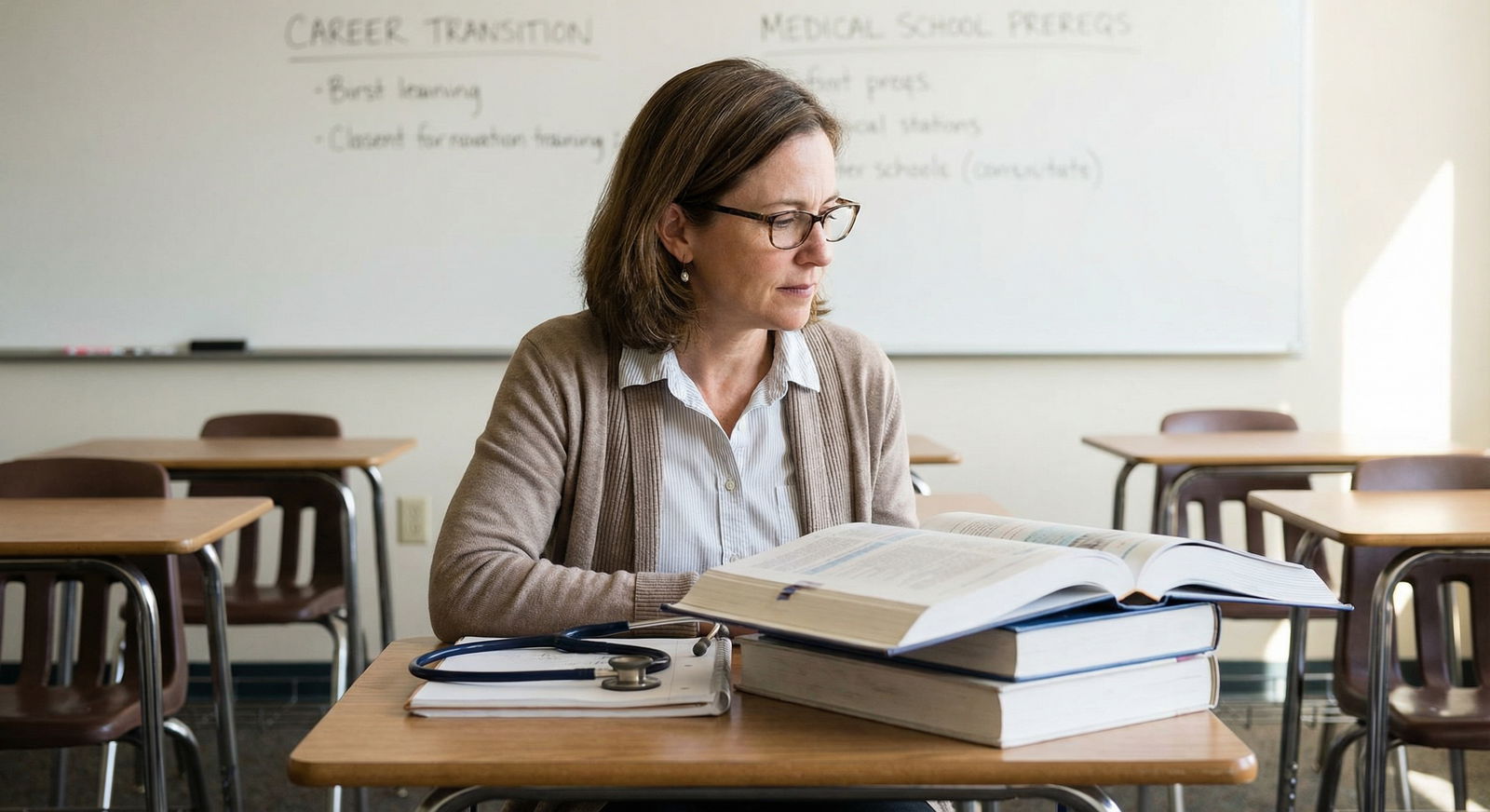

I have watched otherwise strong non-traditional applicants tank interviews and secondaries for one reason: they mishandled the “So…why now?” conversation. And admissions committees are hypersensitive to that question. They have seen mid‑career pivots go very, very wrong.

Let me walk you through the mistakes that keep getting repeated—and how to stop making them.

Mistake #1: Treating Your Pivot Like a Confession Instead of a Professional Narrative

Older applicants often talk about their past as if they are apologizing for it.

You see versions of this everywhere:

- “I know I’m getting a late start…”

- “I originally wasted time in another career…”

- “I finally realized medicine is what I should have done all along…”

That reads like guilt. Or regret. Or poor judgment. None of those inspire confidence.

Your past career is not a crime scene. It is your evidence.

Programs worry about three things with an older premed:

- Will you finish the marathon, or bail when it gets hard?

- Are you chasing a fantasy rather than understanding the job?

- Are you fleeing something (burnout, failure, boredom) rather than moving toward something clear?

When you frame your story like a confession, you feed all three fears.

Better frame: You made a series of rational decisions based on who you were and what you knew at the time. Then, with more exposure, data, and self-awareness, you changed course—deliberately.

That means you need to stop phrases like:

- “I wasted 10 years in finance.”

- “I felt lost for most of my 20s.”

- “I never really knew what I wanted to do.”

You can feel those things. Fine. But do not center them.

Instead:

- “I spent 10 years in finance, where I learned X, Y, Z.”

- “Over time, I found myself drawn more to A and B, and less to C.”

- “As I gained more exposure to clinical settings through [specific activity], the fit with medicine became clear.”

You are not confessing. You are presenting a coherent career trajectory that leads logically into medicine—even if the time line is unconventional.

Mistake #2: Making the Pivot About Your Feelings Instead of the Work

Older premeds often overshare about their emotions and undershare about the work.

“I realized I wanted to help people.”

“I just did not feel fulfilled.”

“I always dreamed of being a doctor.”

Those sentences are background noise in admissions. Every file has some version of that. And when it comes from a 35‑year‑old software engineer, it can sound like a midlife crisis in essay form.

The pivot has to be about the work of medicine, not your inner emotional weather.

Admissions committees want evidence that you:

- Understand the day‑to‑day reality of being a physician

- Have seen the ugly parts (documentation, bureaucracy, sleep deprivation, sick systems) and still want in

- Are motivated by more than vague “service” platitudes

So if your personal statement or interview answer sounds like “feelings, feelings, feelings,” with only a thin layer of actual clinical exposure, you look risky.

You should be talking about:

- Concrete experiences: scribing, EMT work, hospice volunteering, MA work, shadowing with specific follow‑up

- Moments that showed you specific roles of physicians: decision‑making, longitudinal care, dealing with uncertainty, teaching patients

- How your previous career strengths translate into those realities

If you cannot articulate what a physician actually does all day in your chosen field, your “I want to help people” is just noise. And committees will pick up on that instantly.

Mistake #3: Telling a “Sudden Epiphany” Story That No One Believes

The “lightbulb moment” story is wildly overused—and deadly for older applicants.

“I had this one night in the ER with my sick grandmother and I knew right then I had to become a doctor.”

“I watched a surgery on YouTube and something clicked.”

“I read When Breath Becomes Air and realized medicine was my calling.”

These are fine as part of your emotional narrative, but if your pivot rests on a single moment, it sounds impulsive. Program directors hate impulsive.

You have years of adult life behind you. Your career decision should sound like the product of:

- Accumulated experience

- Pattern recognition

- Repeated exposure

- Tested interest

Not a cinematic plot point.

Instead of:

- “That one moment changed everything…”

Use:

- “That experience forced me to confront what I found meaningful in my work. Over the following year, I tested that insight by doing X, Y, and Z in clinical settings. The more I leaned in, the more the fit with medicine became obvious.”

You want the pivot to look inevitable in hindsight. Not whimsical.

Mistake #4: Ignoring or Minimizing Practical Realities That Everyone Is Thinking About

This one is brutal.

Older premeds often dodge the practical questions:

- “You’re 38. Why does this make sense financially?”

- “You have two kids. How will you manage medical school and residency?”

- “You have a mortgage and a spouse. Does your partner support this?”

When you wave your hand and say “We’ll figure it out” or “I know it will be hard but I’m passionate,” you sound naïve.

Here is what the committee is really asking:

“Have you looked this monster in the eye and done the math?”

You do not need to give a full financial planning seminar, but you must show:

- You understand the length of training and opportunity cost

- You have run at least a basic financial plan (loans, savings, spousal income, lifestyle changes)

- You have discussed this with the stakeholders in your life and have their buy‑in

A strong answer sounds like:

- “I recognize that starting at 37 means I will likely be in full practice in my mid‑40s. My spouse and I have reviewed our finances closely; she plans to continue working as a nurse, we have downsized our housing, and we have a clear plan for childcare during clinical years. We are entering this eyes open.”

Some of you will be tempted to lie or gloss over things because they are not fully sorted yet. Do not. Be honest about challenges and concrete about your planning.

This is one place where being older is an advantage—you’re supposed to be realistic.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| <24 | 55 |

| 24-26 | 28 |

| 27-29 | 10 |

| 30-34 | 5 |

| 35+ | 2 |

You are a smaller percentage of the pool. That just means you cannot afford sloppy answers.

Mistake #5: Over‑Selling or Under‑Selling Your Previous Career

Nontrads tend to fall off one of two cliffs:

Cliff 1: Trashing the old career.

Cliff 2: Treating the old career like unconnected baggage.

On Cliff 1, you say things like:

- “Corporate law was soul‑sucking.”

- “I hated finance; it added nothing to society.”

- “Tech was just about making rich people richer.”

Now the interviewer is thinking: “So when medicine gets bureaucratic and political—and it will—are you going to sour on this too?”

On Cliff 2, you barely connect your prior work to medicine:

- “I was a high school teacher for 8 years. Then I decided to switch to medicine because I wanted to help people in a different way.”

…And then nothing specific about what teaching gave you or how it shapes the physician you’ll be.

The right move is to show:

- You respect what you did before.

- You extracted real skills and insights from it.

- Those skills are not generic fluff; they are directly relevant to medicine.

For example:

- A former teacher should not just say “I learned communication.” They should say, “I learned how to explain complex topics to anxious parents in plain language and manage group dynamics in a room of 30 teenagers. That translates directly into guiding families through difficult diagnoses, especially when there is fear and misinformation.”

- A former engineer should not stop at “problem‑solving.” They should talk about structured troubleshooting, systems thinking, risk assessment under uncertainty—core to clinical reasoning.

If you cannot articulate specific, concrete value from your prior career, committees will see you as a first‑career applicant with extra steps and more baggage.

Mistake #6: Sounding Defensive, Bitter, or Overly Self‑Justifying

You will be asked—explicitly or implicitly—why you did not do this earlier.

You can either answer like a professional. Or like a cornered defendant.

Defensive answers sound like:

- “Well, I did not have the resources to apply when I was younger.”

- “My parents forced me into engineering; I always wanted medicine.”

- “If I had known then what I know now, I would have gone straight to med school.”

These might all be true. They still sound like blame and regret. Not like someone ready to handle the constant feedback and hierarchy of medical training.

A stable, grounded answer sounds like:

- “At 18, I did not have accurate information about what medicine required, and I was stronger in other areas. My first career gave me X and Y, but as I gained more exposure to clinical environments, I realized that medicine aligned better with my long‑term strengths. I am glad I did not apply at 22—I would not have been ready. I am ready now.”

Notice the shift:

- Less: excuses, resentment

- More: reflection, maturity, ownership

You are not on trial. You are explaining how your previous chapters make this one stronger.

Mistake #7: Using the Wrong Level of Detail in the Wrong Place

Older applicants frequently misjudge how much detail to share.

Two common extremes:

- Oversharing life story trauma to justify the pivot.

- Staying vague and generic about key decisions.

If you spend 70% of your personal statement unpacking your divorce, burnout, illness, or family drama, then tack on “and now I want to be a doctor,” it looks like you need therapy, not an MD. Harsh, but this is how some adcoms read it.

On the other hand, if your essay reads:

- “I spent 10 years in another career but always had medicine in the back of my mind”…

…and you never explain what changed, what you did to test the interest, or how you confirmed your fit, that feels shallow.

The right balance:

- Mention life events briefly when they are genuinely causal (job loss, caregiving experience, major illness). One or two sharp paragraphs, not an autobiography.

- Spend more space on actions you took once you started considering medicine: courses, certifications, clinical hours, conversations with physicians, specific responsibilities you took on.

Your pivot story should be less “here is my childhood” and more “here is the decision‑making process I went through as an adult.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Established Career |

| Step 2 | Initial Discontent or Trigger |

| Step 3 | Exposure to Clinical Work |

| Step 4 | Deliberate Exploration |

| Step 5 | Formal Academic Preparation |

| Step 6 | Reassessment with Family/Finances |

| Step 7 | Committed Decision to Pursue Medicine |

| Step 8 | Application and Interviews |

If your story jumps from A to H with nothing in between, that is a problem.

Mistake #8: Forgetting That Your Pivot Story Must Be Consistent Everywhere

Admissions committees compare your:

- Primary application (AMCAS/AACOMAS)

- Secondary essays

- Letters of recommendation

- Interview answers

Older premeds often tweak their story slightly for each, and the inconsistencies show.

Examples I have seen:

- Primary essay: “I decided to pursue medicine after working as a PA for several years.”

Interview: “I really started thinking about medicine in college, but my grades weren’t good enough.”

LOR: “He first mentioned medicine seriously during his MBA program.”

None of those are fatal alone. But together, they read as fuzzy and possibly disingenuous.

You need one clear, anchor narrative:

- Roughly when you started seriously considering medicine

- What triggered that shift

- What you did after that to pursue it

- How your view evolved as you gained more exposure

Then you repeat that core outline, adapted to the format, but not contradicted.

Write it out once, plainly, in a single page for yourself. That becomes your internal reference. Every essay and answer needs to align with that backbone.

| Element | Example for a 34-year-old former engineer |

|---|---|

| First serious consideration | Age 30, after volunteering in free clinic |

| Trigger event | Working with uninsured patients on tech project for hospital |

| Early tests of interest | 1 year volunteering, 100+ hours shadowing IM and FM |

| Academic preparation | Post-bacc starting at 31, completed core prereqs |

| Decision confirmation | Continued scribing during post-bacc, sought mentorship from physicians |

| Practical planning | Financial review with spouse, childcare and housing plan |

You are not inventing a story. You are locking in a coherent version of the true story.

Mistake #9: Letting Your Pivot Dominate the Whole Application

This one is subtle.

Because your career change feels central to you, you make it central to everything:

- Personal statement: 80% about the pivot

- Secondaries: every “challenge” or “diversity” or “resilience” prompt answered with some version of the pivot

- Interviews: you keep circling back to “why I changed careers”

By the end, the committee knows why you left accounting. They do not know how you think. Or how you work in a team. Or whether you can handle feedback. Or what you care about in patient care.

Your pivot is one dimension. Not your entire identity.

You still have to show:

- Academic capability (especially recent, rigorous science work)

- Clinical understanding and maturity

- Teamwork and communication in high‑stakes settings

- Longitudinal commitment to something—anything—that shows you can stick with a hard path

If every essay answer is some form of “As an older applicant switching from marketing to medicine…,” it starts sounding like a gimmick. You are more than your pivot. Show it.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Pivot Explanation | 25 |

| Clinical Exposure & Insight | 35 |

| Skills from Prior Career | 20 |

| Future Physician Identity | 20 |

If your statement is 60–70% pivot explanation, you are overdoing it.

Mistake #10: Not Practicing the “Why Medicine, Why Now?” Answer Out Loud

Older premeds often think, “I’m an adult. I know my story. I’ll just talk about it.”

Then they sit down in front of an interviewer and ramble for 6 minutes, overshare, backtrack, or start crying.

Do not improvise this. Ever.

You need a crisp, 60–90 second core answer to:

- “So why medicine now?”

- “Why change careers at this stage?”

- Variants like “Walk me through your path.”

It should:

- Start with a one‑sentence summary of your previous career.

- Briefly state what began to feel misaligned.

- Describe the specific experiences that pulled you toward medicine.

- End with a confident, future‑focused statement about who you will be as a physician.

Something like:

“I spent 11 years as a mechanical engineer, mostly in medical device design. I enjoyed the problem‑solving, but over time I realized I was too removed from the people actually using the products. Working closely with physicians and nurses during device testing, and later volunteering in a free clinic, I found I was most energized when I was in the room with patients, navigating uncertainty with them. Over the last four years I have taken a full post‑bacc, worked as a scribe in internal medicine, and confirmed that I want the responsibility of clinical decision‑making and longitudinal care. I am entering medicine later, but with a clear understanding of the work and the systems perspective that my engineering background provides.”

That is calm. Rational. Grounded. Not breathless. Not apologetic.

Then you build out a few longer variants (2–3 minutes) for more open‑ended prompts. But the core stays the same.

Mistake #11: Failing to Demonstrate Stamina and Adaptability for the Long Haul

The other unspoken concern with older applicants: "Can you actually handle being a trainee again?"

Age itself is not the issue. Rigidity is.

If you insist on:

- Emphasizing your seniority in every answer ("In my 15 years as a manager…")

- Sounding like you expect special treatment or shortcuts because you are “bringing so much experience”

- Making it clear you hate being told what to do

You will get quietly screened out.

Your pivot explanation must implicitly answer:

- “I can be a learner again.”

- “I am not above grunt work.”

- “I can function in a hierarchy where people 10 years younger than me have formal authority.”

Bring up experiences where you:

- Returned to being a beginner (taking hard science classes after years away, learning a new skill from scratch)

- Took feedback from much younger supervisors or colleagues without ego

- Worked night shifts, or did unglamorous tasks, and did them well

A small phrase like “I enjoyed learning from my younger classmates in organic chemistry, especially when they saw things differently than I did” goes a long way.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Stamina for training years | 80 |

| Financial/Family stress impact | 70 |

| Adaptability to hierarchy | 65 |

| Understanding of physician workload | 60 |

| Academic readiness in sciences | 55 |

If you ignore these concerns in your story, the committee will fill in the gaps. Not in your favor.

Your Next Step: Write the Pivot Story You Actually Need

Do this today. Not “sometime this week.” Today.

Open a blank document and, in plain language, answer these five questions in 1–2 paragraphs each:

- What exactly did you do in your prior career, day to day?

- What specific experiences started to misalign that work with what you wanted long‑term?

- What concrete exposures to medicine (jobs, volunteering, shadowing) pushed you from “interested” to “committed”?

- How have you tested this decision academically, practically, and with the people in your life?

- How will your previous career make you a better physician in ways that are specific, not generic?

Then read it out loud once. Anywhere you hear apology, melodrama, or vagueness—fix it.

That document becomes the spine of your personal statement, your secondaries, and your interview answers. If you get that right, your age stops being a liability and starts looking like what it actually is: an asset, with a story that makes sense.