Is It Too Late to Turn Back? Handling Doubt Midway Through the Transition

What happens if you’ve already sunk years, money, and your ego into becoming a doctor… and now you’re scared you might have picked the wrong life?

That’s the thought that sits in the back of your skull at 2 a.m., right?

Not “I’m a little nervous.”

More like: “If I realize this was a mistake, I’ve wrecked my career, my finances, and maybe my relationships. And everyone will see me as a failure.”

Let me say this up front: you are not the only one thinking this.

You’re just one of the few honest enough to say it out loud.

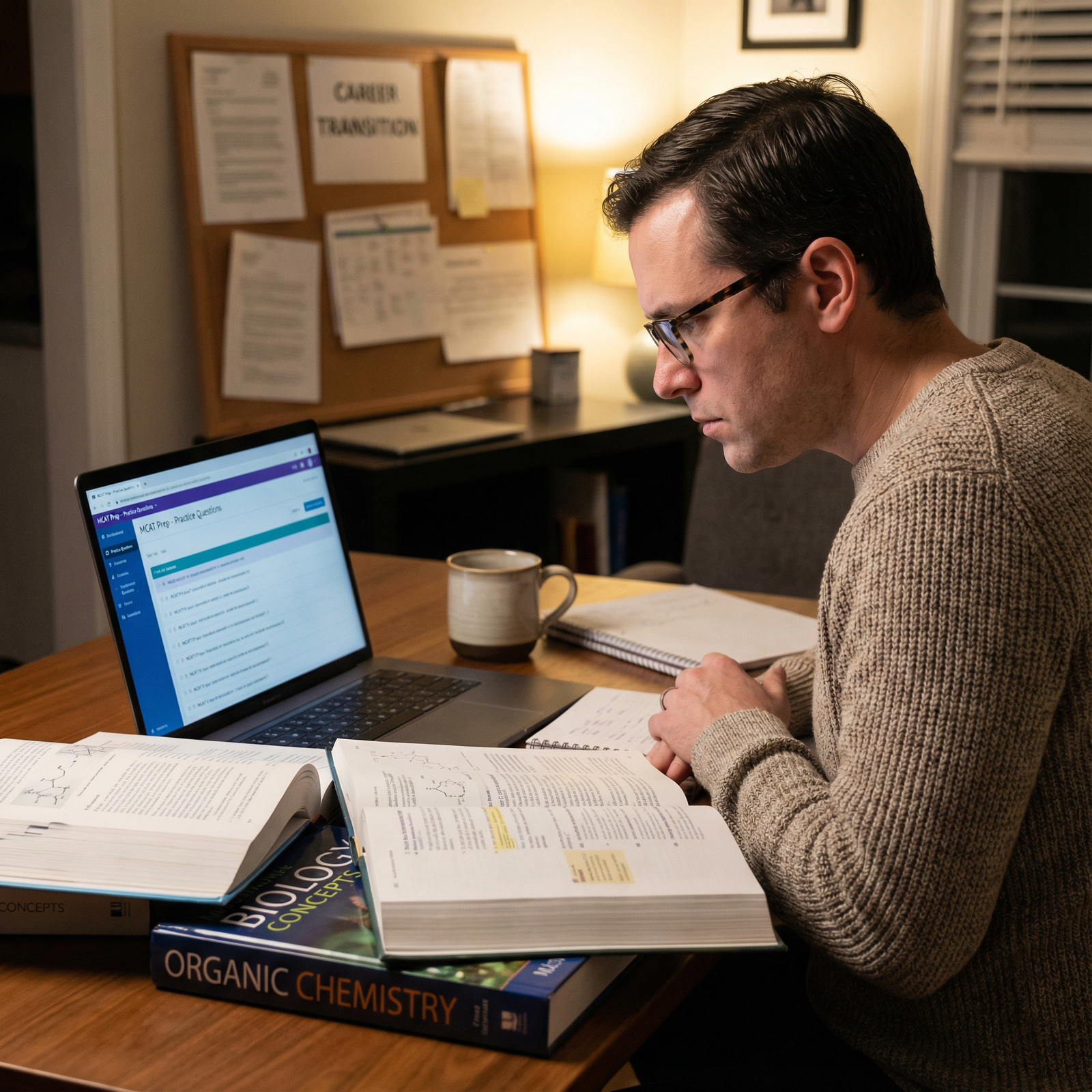

You’re probably somewhere in the middle of the transition:

- You’re a few semesters into your prereqs at 28, 32, 40.

- Or you quit a job that actually paid you, and now you’re living off savings or loans.

- Or you told your whole family and your coworkers, “I’m going to med school,” and now you feel trapped by your own announcement.

And now the doubt hits:

Did I start too late?

Is it still reversible?

What if I push through and regret it even more?

Let’s pick this apart without sugarcoating it.

Step 1: Separate Panic From Data

There’s “I had a bad orgo exam and want to disappear.”

And then there’s “On paper, this path might not be viable or might not match what I actually want.”

Those are not the same problem.

Right now, your brain probably blends everything into one giant catastrophe. So first, pull it apart:

Ask yourself three different questions:

Am I doubting my ability to get there?

(Grades, MCAT, time, finances, burnout.)Am I doubting that I’ll like the job if I actually get there?

(Actual daily life of doctors, residency horror stories, family time, lifestyle.)Am I doubting this because I’m exhausted and scared, not because it’s truly wrong?

(Sleep-deprived, isolated, anxious, perfectionistic.)

Most nontraditional people I’ve talked to have all three going on, but one is usually loudest.

If you don’t know which one it is, you risk making permanent decisions from temporary misery.

Step 2: Write Down the Actual Worst-Case Scenarios

Yes, the thing you already do in your head, but this time you do it properly, not as vague doom.

Be concrete. Brutal. Specific.

For example, if you’re 30, working part-time, doing prereqs:

Worst case if you keep going and it doesn’t work:

- You spend 3–5 years on prereqs, MCAT, applications.

- You spend $X on tuition and lost income.

- You don’t get in, or you realize late you don’t want this.

- You end up pivoting back into another career in your 30s or early 40s with some extra science and maybe some debt.

Worst case if you stop now:

- You feel embarrassed in front of people you told.

- You feel like “the person who couldn’t hack it.”

- You go back to your previous career or find a variant of it.

- You always wonder if you could have made it but never find out.

Neither of these is pretty. But neither is “my life is over and I’ll be living in a cardboard box.”

Your anxious brain tells you the worst-case is catastrophic and irreversible. It almost never is. It’s ugly, humbling, expensive, but survivable.

And you know what? You’ve already survived things.

This wouldn’t be the first time.

Step 3: Look at Age and Timeline Without Lying to Yourself

This is where nontrads get stuck:

“I’ll be 40 when I finish residency.”

“I’ll have classmates 10–15 years younger.”

“I’ll be behind financially forever.”

You already know the math, but seeing it clearly helps.

| Starting Age | Start Med School | Finish Residency (3 yrs) | Finish Residency (5 yrs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 30–31 | 33–34 | 35–36 |

| 30 | 33–34 | 36–37 | 38–39 |

| 35 | 38–39 | 41–42 | 43–44 |

| 40 | 43–44 | 46–47 | 48–49 |

If those numbers make you nauseous, yeah. Me too.

But ask this:

If you don’t do medicine, what will you be doing at 40? Or 45? Or 50?

You’ll still be that age. Just without this path.

The real question isn’t “Will I be old?”

It’s “Will the tradeoffs feel worth it to me at that age?”

That’s not something a stranger on the internet can answer. But you can have a pretty honest guess if you stop trying to impress anyone in your imaginary audience.

Step 4: Test Drive the Actual Job, Not the Fantasy Version

A lot of nontrads fall in love with the idea of medicine: Helping people. Intellectual challenge. Respect.

But the day-to-day reality? Different beast.

If your doubt is: “What if I get there and hate it?”

You need real contact with the job now, not later.

And I don’t mean one shadowing shift where everyone’s on their best behavior.

I mean:

- Multiple shadowing experiences in different settings (clinic, hospital, primary care, ED).

- Following residents, not just attendings. They’re closer to the grind you’re signing up for.

- Talking to physicians who are 40+, especially those who started later or have kids.

Listen for:

- How often they mention paperwork, EMR, admin, insurance.

- How tired they look at 3 p.m. on a normal Tuesday.

- How they talk about family, hobbies, sleep.

That’s not to scare you off. It’s to stop you from chasing a filtered Instagram version of medicine.

If you see all of that and still feel pulled? That’s data.

If you see all of that and your stomach drops? Also data.

Step 5: Be Honest About Money and Burnout Risk

Here’s where nontraditional paths can be punishing:

You don’t have infinite time to recover from financial screwups.

You might have:

- A mortgage.

- Kids.

- Aging parents.

- Loans from a previous degree.

You can’t pretend you’re 21 and “we’ll see what happens.” That’s not anxiety talking; that’s reality.

If your doubt is mostly financial, you’re not selfish. You’re responsible.

You need a rough budget and debt projection, not vibes.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| No Med School | 20000 |

| Med School Low Debt | 250000 |

| Med School High Debt | 400000 |

Then ask:

- If I took on this kind of debt and finished at ~X age, does the payoff and personal meaning outweigh the cost?

- If the answer is “only if I match derm or ortho or plastic,” that’s dangerous. You cannot plan your entire financial future on beating the odds into the most competitive specialties.

You also need to factor in burnout:

If you’re already at the edge in prereqs, working, caring for kids, sleeping 5 hours…

Residency will not be gentler.

That doesn’t mean you can’t do it. It means you need a realistic picture of what your mind and body can handle over sustained years.

Step 6: Give Yourself a Structured “Decision Window”

The worst feeling is limbo. Not fully in. Not fully out. Just… stuck.

Instead of sitting in that forever, set a decision window. Something like:

“I’m going to:

- Finish this semester (or this year)

- Take X specific actions (shadow A, talk to B, meet with advisor C)

- Then on [date], I’ll sit down, look at my notes, and decide whether I continue, pause, or pivot.”

Write that date down. Treat it like an appointment.

Between now and then, your only job is:

Gather data.

Not decide every five minutes whether you’re a failure.

You’ll still obsess, of course, but at least you’ve built a structure around it.

Step 7: Talk to People Who Don’t Have a Stake in Your Image

The people you’re probably most afraid of disappointing:

- Parents

- Partner

- Friends who bragged about you

- Old coworkers who said “Wow, med school? That’s amazing.”

They are the worst people to use as your decision mirror. Not because they’re bad, but because they see a story about you, not your internal reality.

Find people who:

- Know the path (physicians, residents, upperclass med students, nontrads ahead of you).

- Don’t need your choice to validate their own life.

Ask them ugly questions:

- “If you could go back, would you do medicine again? Knowing what you know now?”

- “What’s the part of your day you dread the most?”

- “How often do you feel like it wasn’t worth it?”

And then shut up and listen. Don’t try to impress them. Don’t try to sound “committed.”

You don’t owe anyone the performance of certainty.

Step 8: Define What “Turning Back” Would Even Look Like

The phrase “turning back” sounds like you walk away and everything before was wasted.

That’s almost never true.

What actually happens:

- You’ve taken science classes → you can pivot into PA, nursing, PT, OT, public health, research, biotech, teaching, etc.

- You’ve shown you can go back to school as an adult → that’s a huge signal to employers.

- You’ve clarified what kind of work you don’t want → also valuable.

Turning back doesn’t mean “go back to exactly what I did before and pretend this never happened.”

It might mean:

- “Not MD/DO, but PA or NP fits my life better.”

- “I love patient care but not the training path; maybe clinical psychology or counseling.”

- “I like science, but I hate the clinical chaos; maybe lab research, pharma, data.”

You’re not undoing your story. You’re changing its direction.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Nontraditional Applicant Mid-Transition |

| Step 2 | Continue Toward MD/DO |

| Step 3 | Pivot to Other Clinical Role |

| Step 4 | Return to Previous Field |

| Step 5 | New Non-Clinical Path |

| Step 6 | PA/NP/PT/OT/Nursing |

| Step 7 | Public Health/Policy/Research |

Step 9: Decide What You Can Live With Regretting Less

Here’s the part that’s actually terrifying:

There is no path with zero regret.

If you go all-in on medicine, you may later regret:

- Time lost with family.

- Debt.

- Burnout.

- Missing out on other careers that would’ve fit better.

If you walk away now, you may later regret:

- Never knowing if you could’ve made it.

- Wondering “what if” at 45 when your life is stable but feels a bit hollow.

- Feeling like you quit because you were scared, not because it was wrong.

You’re forced to choose which flavor of regret you can tolerate.

For some people, the regret of not trying is worse.

For others, the regret of pushing into something misaligned is worse.

There’s no moral high ground in either choice. You’re not braver for suffering unnecessarily, and you’re not weak for stepping away from a path that doesn’t fit.

Step 10: You’re Allowed to Change Your Mind. Even Late.

This is the part nobody tells you because they want your “story” to be clean:

You can:

- Be halfway through prereqs and choose a different path.

- Be after one application cycle and choose not to reapply.

- Be accepted and decide to defer or withdraw.

- Even be in med school and decide, “No. This isn’t my life.”

Is it messy? Yes.

Does it suck to explain? Absolutely.

Does it make you a failure? No. It makes you a person whose information changed.

I’ve seen:

- A 33-year-old nontrad finish prereqs, crush the MCAT, then walk away because she realized she wanted a family life that residency would destroy for her personally. She’s now a PA, very happy.

- A 29-year-old who almost quit after bombing orgo, stayed, got into a DO school, and is now a sleepy but content FM resident.

- A 40-year-old engineer who went all the way to M3, then left, went into health tech, and earns well, actually sees his kids, and still works “in medicine” without the pager.

Different people. Different tolerable regrets.

You’re trying to pick yours.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Financial Concerns | 30 |

| Fear of Burnout | 20 |

| Family/Time Tradeoffs | 20 |

| Self-Doubt/Imposter Syndrome | 15 |

| Doubts About Loving Medicine | 15 |

If You Do Nothing Else, Do This

Stop trying to decide your entire future in your head at 1:30 a.m. when you’re exhausted. That’s when your brain is a horror movie writer, not a strategist.

Set a decision window and a list of actions: who you’ll talk to, what you’ll shadow, what financial numbers you’ll actually run.

Tell one person the unvarnished truth: “I’m scared I might have made a mistake and I don’t know what to do.”

Not the polished, committed version. The real one.

You’re not too late to turn back.

You’re also not too late to keep going.

You’re just in the ugly, in-between middle where everything feels fragile and reversible and permanent at the same time.

It won’t always feel like this.

FAQ (Exactly 6 Questions)

1. Am I too old to start medical school if I’ll be in my mid-to-late 30s?

No, you’re not “too old,” but you are in a different risk category. Programs absolutely accept people in their 30s and even 40s. I’ve seen 38-year-old MS1s and 42-year-old nontrads in DO schools. The real questions are: does the lifestyle line up with the life you want at 45–55, and can you tolerate starting your attending career later financially and personally? If you’re expecting it to feel like being 24 in med school, it won’t. That doesn’t make it wrong—it just makes it different.

2. How do I know if my doubts mean I should quit or just push through?

Doubt by itself doesn’t mean quit. Everyone doubts. If your doubts are mostly: “This is hard and I’m scared,” that’s normal. If your doubts are: “I hate the day-to-day work I see doctors doing,” “I cannot reasonably handle the financial or emotional cost,” or “My actual values don’t match this lifestyle,” that’s a bigger red flag. The test I like: after real shadowing, real financial math, and real conversations with physicians, does the pull toward medicine survive? If it shrinks more every time you get more information, listen to that.

3. What if I’ve already told everyone I’m going to be a doctor and now I’m embarrassed?

Then you’re human. You’re allowed to change your mind after getting more information. People will have opinions for about 3 days and then go back to their own problems. The harsh truth: keeping yourself on a wrong path for 10–15 years just so you don’t have one awkward conversation is a terrible trade. If you pivot, you can literally say, “Once I got into the thick of it, I learned a lot more and realized a different path fit better. It wasn’t easy, but it was the right call.” That’s not failure. That’s growth.

4. Is it irresponsible to continue if I’m already worried about debt?

It’s not irresponsible to be worried; it’s irresponsible to ignore that worry. Continuing can be responsible if: you’ve run the numbers, considered cheaper schools and loan repayment options, and accept the tradeoffs consciously. It’s reckless if your whole plan is, “I’ll just match a super competitive specialty and make bank,” or “Something will work out.” You don’t need certainty, but you do need a plan that doesn’t rely on fantasy.

5. What if I commit to this and later decide in residency or as an attending that I hate it?

Then you’ll be like a surprising number of physicians who quietly pivot. People leave clinical practice for admin, consulting, industry, public health, informatics, teaching. Is that ideal? No. Is it a waste? Not necessarily. But yes, it’s a lot of cost and sacrifice to end up doing something adjacent. That’s why you’re smart to wrestle with doubt now instead of pretending everything is fine just to protect your ego.

6. How do I stop obsessing about this decision every single day?

You probably won’t stop completely, but you can make it less consuming. Set a specific time once a week where you’re allowed to “worry on purpose” and review your notes, pros/cons, and plans. The rest of the week, when the thoughts pop up, you tell yourself, “Not now. Saturday at 3 p.m. is worry time.” Also, do the unsexy stuff: sleep more than 5 hours, eat actual food, move your body. A sleep-deprived brain will make everything feel like the apocalypse. You’re not going to think clearly about a 10-year decision when you’re barely surviving today.

Key points:

- Doubt in the middle of a nontraditional transition is normal; it’s not automatic proof you chose wrong.

- You need real data—shadowing, financial numbers, honest conversations—to decide whether to keep going or pivot.

- “Turning back” isn’t failure; it’s choosing which regret you can live with and building a life that actually fits you, not your imagined audience.