The romantic story about “following your passion into medicine” leaves out the ugly part: the debate about you that happens in rooms you will never see.

I’m talking about the closed‑door conversations when you quit a high‑paying career to chase medicine. Admissions committees, pre‑health advisors, even attendings you shadow—everyone has an opinion. And they do not all agree.

You feel like you’re wrestling with your own doubts and family pressure. But behind the scenes, they’re wrestling with something else: are you a courageous, high‑yield, mature applicant… or a midlife crisis with good vocabulary?

Let me walk you through what they actually say when your file lands on the table.

The First Reaction: “Why Did They Walk Away From That Salary?”

Nobody reads your application cold. They scan it with a narrative in mind.

Corporate consultant making $180K. Engineer with a decade at a FAANG company. Partner‑track lawyer. Senior IB analyst. I’ve seen all of those. The first comments in committee are rarely about your GPA. They’re about the decision.

The unfiltered questions sound like this:

- “They were making how much and now want to be a student again?”

- “What’s the story behind this pivot?”

- “Is this a burnout case or the real deal?”

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: the higher your prior career status and income, the more suspicion you trigger initially. You think your background screams “impressive.” Some committee members see “flight risk” or “doesn’t understand what they’re giving up.”

There’s an internal split:

- Older physicians—especially those who trained before medicine became so corporatized—often like late‑career switchers. “Someone walking away from that kind of money to do this? That’s commitment.”

- Some younger faculty and financially burned‑out attendings are more cynical: “Do they think this is some noble calling that’ll magically feel better than their last job? Wait until they’re post‑call doing prior auths for $250K instead of $400K.”

You need to know this because your job is to direct that debate before it starts. If they’re going to argue about why you left your old life, you want the default frame to be: “This person knew exactly what they were giving up and walked anyway.”

The Unspoken Fears About Nontraditional Career‑Changers

The public line is always supportive—“We value diverse backgrounds,” “Nontraditional applicants enrich the class.” Sure. But that’s the brochure.

Behind closed doors, the real concerns show up fast:

1. “Can they handle going backwards—socially and financially?”

They’ve seen it go badly. I remember a committee discussion about a 33‑year‑old ex‑engineer:

- Stellar stats: 3.9 science GPA, 520 MCAT

- Great LORs, strong clinical exposure

- Left a ~$200K job

Half the room: “Top‑tier candidate.”

One senior faculty member cut in: “I’ve watched people like this implode when they realize they’re taking orders from 28‑year‑old residents making less than they did as interns in their old career.”

That fear is real. They have seen:

- Former executives bristle at being “just a student”

- High‑earning professionals struggle with being broke again

- People underestimate how rough the training years feel in your 30s and 40s

They’re testing one key thing: your ego flexibility. If they sniff entitlement or “I’m above this grunt work,” it’s over.

2. “Is this a breakup rebound?”

Many committees quietly categorize applicants as:

- “Always wanted medicine, detoured, now returning.”

vs. - “Burned out on previous field, hoping medicine feels different.”

You want to be read as the first, not the second.

The rebound story is what scares them: person hates consulting, hates law, hates tech, and decides medicine must be more meaningful, more human. Sometimes that’s true. Often, they don’t realize they’re just trading one unfair system for another.

3. “Are they running toward medicine or just running away?”

One dean said it bluntly in a meeting:

“I don’t want to admit someone who’s just fleeing a miserable life. I want someone walking knowingly into this one.”

Your file needs to prove that. Not just say it.

How Committees Actually Read Your Story

Let me tell you how your application gets dissected.

There’s a quiet checklist that never appears on any official rubric, but everyone uses it when they see a high‑paying career on your CV.

1. Timeline Scrutiny

They map your life out on a whiteboard in their heads:

- College major and GPA

- First job

- Year where the “medicine story” starts: first clinical volunteering, first shadowing

- Timing of quitting your job

- MCAT date

If they see:

“Worked 8 years, never touched anything remotely clinical, hated my job in year 7, shadowed a doctor twice, applied that same year”

they get nervous.

Contrast that with:

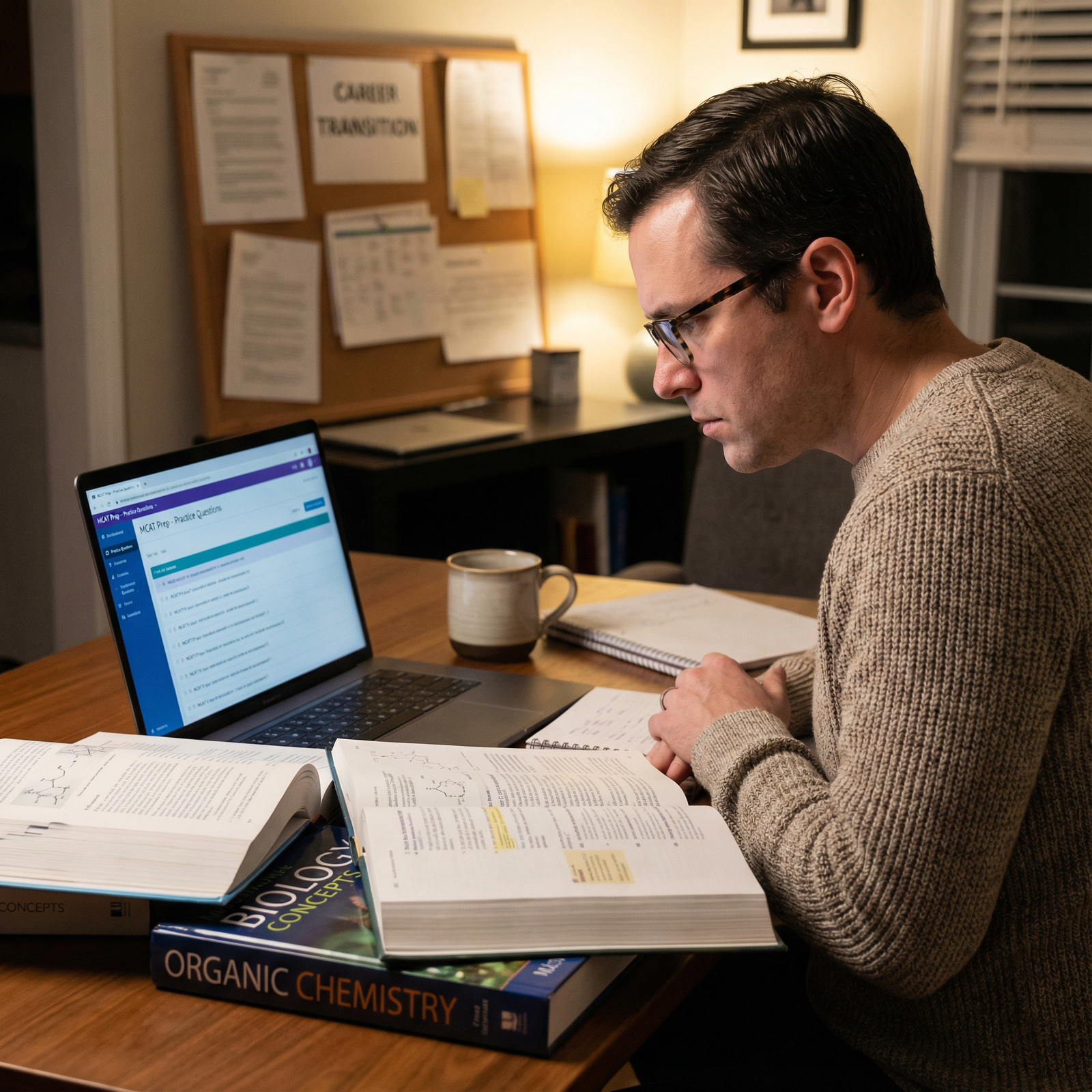

“Even during consulting, they volunteered at a free clinic for 3 years, did weekend EMT shifts, took night classes in orgo, MCAT prep while working, finally quit once they had the prereqs, scores, and sustained exposure.”

The second profile reads like commitment. The first reads like a crisis.

2. Financial Realism Test

They will not ask you this outright in most interviews. But they absolutely talk about it:

- “They have a mortgage and two kids—have they thought this through?”

- “Did they mention a support system?”

- “How are they planning to manage the 10+ year training pipeline?”

Faculty who’ve watched residents crumble under financial pressure are blunt about this. There’s a quiet calculation: Will your life collapse halfway through M3 when loans peak and your spouse is exhausted?

When you casually say in an interview, “I’ve saved enough to cover X years” or “My partner and I sat down with a financial planner and mapped out the next decade,” that lands very differently than vague “I’m prepared to make sacrifices” fluff.

3. Pattern of Grit vs. Pattern of Quitting

Someone on the committee will ask: “Is this a pattern?”

If your CV looks like:

- 2 years in marketing → 1 year in real estate → coding bootcamp → 18 months at a startup → now: medicine

They worry you’re addicted to new beginnings and allergic to staying power.

On the other hand, a long sustained arc—8 years in one field with increasing responsibility, plus parallel signals of interest in medicine—that’s reassuring. It says: “When I commit, I stay. I just realized I had pointed my stamina at the wrong target.”

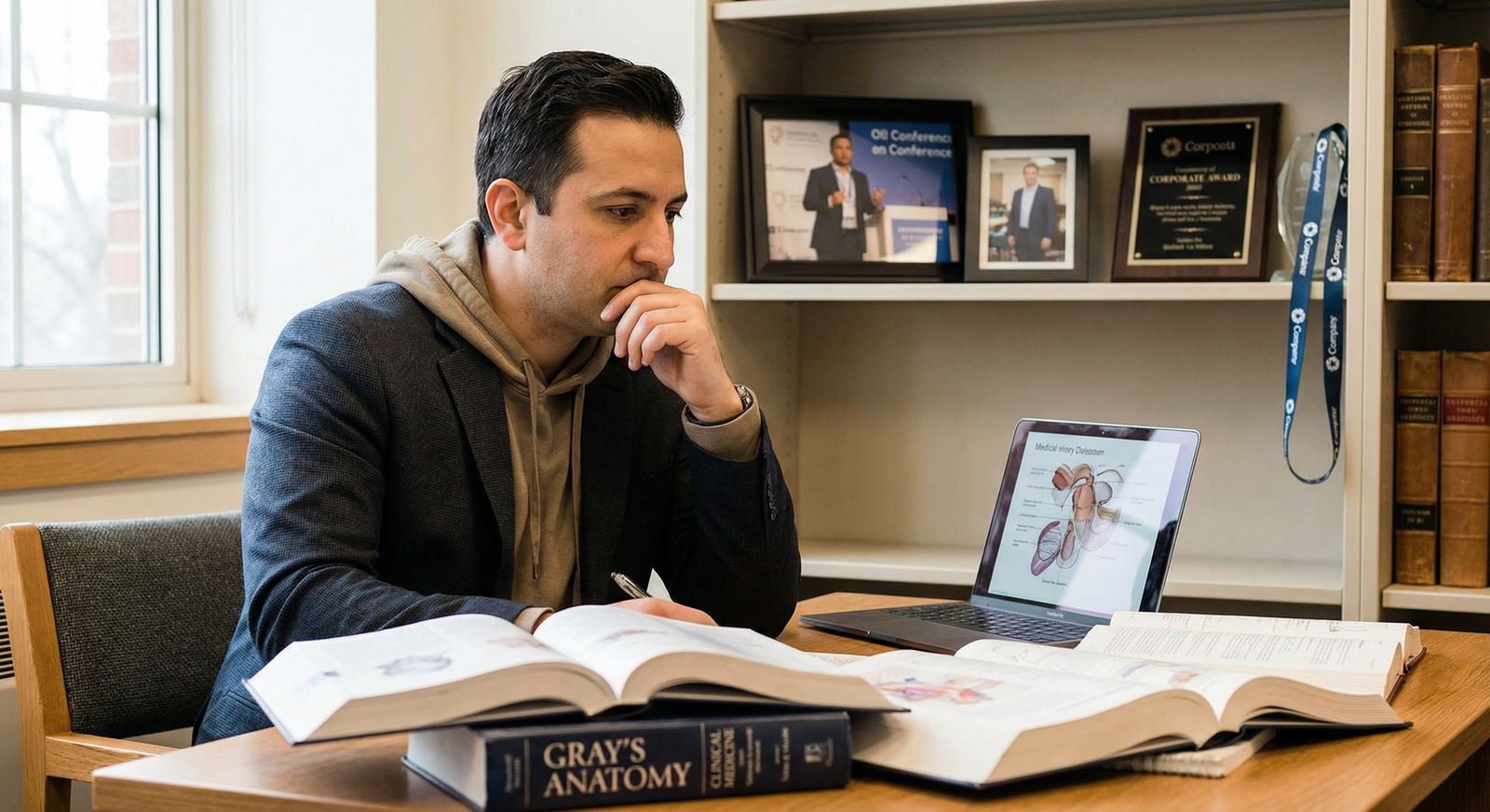

What Attendings and Residents Really Say About You

Your shadowing experiences generate more commentary than you think.

You walk in imagining they’re just chaperones. Some of them are. But others are informal scouts for admissions or future recommendation writers. They go back and say things like:

- “She asked good questions and didn’t flinch in the trauma bay.”

- “He kept comparing everything to how his old company did things. A bit much.”

- “She was humble enough to say she didn’t understand something and asked for clarification without trying to sound smart.”

Attendings notice if you:

- Talk more about your old job than the patient in front of you

- Try to “improve the workflow” on day one because you did Lean Six Sigma once

- Hover uselessly vs. find small ways to help (wiping down a stretcher, grabbing a blanket, being present with a scared patient)

Let me be blunt: some career‑changers try to compensate for imposter syndrome by over‑asserting. Over‑explaining. Over‑selling their prior expertise. It grates on teams fast.

The ones who win support are usually the ones who say, implicitly: “I built skills elsewhere that will help me. But right now, I’m here to be a beginner.”

How to Frame Your Exit from a High‑Paying Job So It Actually Lands

You cannot just say, “I wanted to help people.” Everyone says that, including the 21‑year‑old who’s never had a W‑2 job.

You need to do three things clearly.

1. Show this wasn’t a sudden, emotional jump

Spell out the long arc of your decision:

- When did medicine first seriously enter your thoughts?

- What concrete steps did you take while still employed?

- How long did you test the waters before pulling the ripcord?

The best personal statements from career‑changers read something like:

“Three years ago, I did not say ‘I’m going to quit consulting and go to medical school.’ What actually happened was more incremental and, at times, inconvenient…”

Then they walk you through: late‑night shifts at a hospice, community clinic volunteering, reading physiology textbooks for fun on flights, shadowing a hospitalist during PTO.

That incremental build is what convinces skeptical faculty that you’re not chasing a fantasy.

2. Acknowledge what you’re giving up—specifically

Behind closed doors, committees roll their eyes at vague “I realized money isn’t everything” lines. Of course they know that. Half of them are underpaid physicians.

When you say something more grounded:

- “I turned down a promotion that would have doubled my bonus because it would have pulled me farther from the parts of my work I enjoyed: sitting with clients in the messiness of their actual lives.”

- “I had to confront that walking away meant selling our house and moving into a smaller rental to reset.”

Now it feels real. And you sound like someone who has actually done the math, emotionally and financially.

3. Tie your old life to medicine in a concrete, not cheesy, way

You’re not supposed to pretend your old career was meaningless. That’s actually a red flag. People who frame their entire past decade as a mistake sound unstable.

The trick is to be precise: “Medicine is a better expression of the same underlying drive I pursued in my prior work.”

For example:

- Former engineer: talks about systems thinking, error reduction, process optimization—then shows how that curiosity shifted toward the “most complex system I’d ever encountered: the human body and the healthcare ecosystem wrapped around it.”

- Former teacher: shows continuity in explaining complex ideas under pressure, meeting people where they are, and finding calm amid chaos.

- Former finance or consulting person: focuses not on “dealmaking” but on decision‑making under uncertainty, risk‑benefit analysis, speaking with people in distress over money or health.

You’re not asking them to buy a 180‑degree turn. You’re asking them to see a refined focus.

The Quiet Competition You’re Actually In

Let me break a misconception. Your main competition isn’t only the 21‑year‑old biology major with a 4.0 who’s never had a job. Your real competition, from a committee’s perspective, is:

The other 32‑year‑old with a strong MCAT, high‑income background, and a clean, cohesive pivot story.

Programs usually admit only a limited number of “career‑changer slots” each year. They won’t say that out loud, but you can see it if you look at class profiles. They like balance: some straight‑throughs, some gap years, a handful of older students.

So they’ll ask each other:

- “We already have a 30‑year‑old ex‑engineer we love. Is this candidate bringing something different or stronger?”

- “If we have to pick one nontraditional this cycle, who is most likely to be a steady, successful resident in 7 years?”

Your edge is not just your age or your earnings. It’s your clarity and proof of staying power.

The Emotional Debate You Don’t Hear About

Outside of admissions, there’s another debate you’ll encounter: family, partners, mentors from your old career.

In your world, their questions sound personal. In my world, I’ve watched how those spill into your application indirectly.

- Spouses who are half‑onboard make the path harder. Their doubt shows up when you talk about your support system in interviews.

- Parents who think you’re insane sometimes push you to oversell the “prestige” angle, which makes you sound like you’re chasing status, not service.

- Old bosses who don’t understand medicine write lukewarm letters: “They were very organized and smart” instead of, “This person is the most reliable, mission‑driven colleague I’ve had in 10 years.”

You need to manage that universe consciously. Not everyone in your prior life should be part of your application story. Pick recommenders who genuinely respect your decision—even if they’d never do it themselves.

And you need one or two people in your life who are all‑in on this pivot. Because there will be a day during orgo, or at 2 a.m. after a brutal ED shadowing shift, when something in you whispers, “I walked away from a comfortable life for this?”

You must have already answered that question before you apply. Committees can tell when you haven’t.

What Smart Nontraditionals Do Before They Ever Hit Submit

The ones who end up as the “obvious yes” in the room have done a different kind of preparation. Not just prereqs and MCAT.

They:

- Track their decision in a journal, which later gives them real material for their personal statement—not generic fluff.

- Do sustained clinical work. Not a weekend health fair, not 10 hours of shadowing. Six months to a year, consistently, while still employed if possible.

- Test their tolerance for hierarchy and boredom. Medicine is noble but often mind‑numbing. Sitting with a confused elderly patient for 45 minutes at 3 a.m. isn’t adrenaline; it’s service.

- Talk to residents in their late 30s and early 40s with kids. Not just the single 27‑year‑olds who say, “It’s hard but so worth it!” You want the full, unvarnished version.

- Run the numbers: loans, opportunity cost, time to attending salary, realistic lifestyle in their 40s and 50s.

By the time their application hits the table, the debate in the room is short. People can see the work.

A Brutal But Necessary Check

You’re giving up years of high income. Compound interest. Career momentum. Identity.

So let me give you a question most premed advisors are too timid to ask:

If medicine paid less than your current job—say $80K forever—would you still want to do it?

No, that’s not how the world works. But it’s a clean way of testing what’s really driving you.

If the honest answer is “no,” you’re not alone. That doesn’t disqualify you, but it does mean a big part of your desire is still status, stability, or money. Medicine can give you some of that, eventually. It also extracts a price in time, health, sleep, and emotional wear that a lot of midcareer people underestimate.

Admissions committees are trying—imperfectly—to guess if you’ve actually looked at that equation and still said yes.

You make their job easier when your story shows: “I know what I’m stepping into. I’ve tested the reality. I’ve planned for the loss. And I still want in.”

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | High-paying career |

| Step 2 | First genuine interest in medicine |

| Step 3 | Explore clinically while working |

| Step 4 | Take prereqs/MCAT planning |

| Step 5 | Test lifestyle & financial reality |

| Step 6 | Reassess or adjust |

| Step 7 | Quit or scale back job |

| Step 8 | Full application cycle |

| Step 9 | Medical school matriculation |

| Step 10 | Still committed? |

, Ego/entitlement concerns](https://cdn.residencyadvisor.com/images/articles_svg/chart-admissions-perception-of-career-changers-9589.svg)

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Clear long-term commitment | 85 |

| Realistic financial planning | 75 |

| Evidence of grit | 80 |

| Strong clinical exposure | 70 |

| Vague motivation | 40 |

| [Pattern of quitting](https://residencyadvisor.com/resources/nontraditional-path-medicine/the-red-flags-when-you-quit-your-job-too-early-for-premed-studies) | 30 |

| Ego/entitlement concerns | 25 |

| Profile | Background | Committee Gut Reaction | Why |

|---|---|---|---|

| Applicant A | 32, software engineer, 8 years at same company, 3 years clinical volunteering before quitting | Strong yes | Long arc, stability, tested commitment |

| Applicant B | 29, IB analyst, bounced between 3 firms in 5 years, minimal clinical exposure | Hesitant/no | Pattern of restlessness, rebound concern |

| Applicant C | 35, attorney, 10 years practice, hospice volunteering, excellent writing | Split debate, then yes | Older but thoughtful story and strong service record |

| Applicant D | 31, product manager, hated last job, recent 20 hours shadowing | Likely no | Reads as “running away,” not “toward” |

FAQ: The Behind‑the‑Scenes Debate When You Quit a High‑Paying Career

Does a high‑paying prior career actually help my application, or does it hurt me?

It does both. It helps because it signals maturity, real‑world experience, and usually solid professional skills. It hurts if it looks like you’re reacting impulsively to burnout, or if committees suspect you have no idea what you’re giving up. When your file shows a slow, tested pivot with sustained clinical work and clear financial planning, it moves into the “impressive asset” category. When it looks like a sudden leap fueled by frustration, people start reaching for the “no” pile.Will they judge me for leaving a lucrative, prestigious path?

Yes—and that’s not always bad. Some faculty will admire it; they’re tired of students who chose medicine by inertia at age 18. Others are wary because they’ve watched older trainees struggle. Your job is to preempt that judgment by owning the tradeoff: explicitly acknowledge the loss of income and status and explain why, after testing the reality, you still chose medicine. Hand‑waving or pretending money never mattered to you comes off as naïve or dishonest.How much clinical experience do I need before quitting my job?

Enough that, if you were cross‑examined by a cynical attending, you could calmly say, “I’ve seen the grind up close.” For a midcareer person, 20–40 hours of shadowing is a joke. Think hundreds of hours over months: regular volunteering in a hospital or clinic, EMS shifts, hospice work—while you’re still working if possible. That timeline tells committees you didn’t just dabble; you lived with the decision long enough for the shine to wear off.Will my age and family responsibilities count against me?

They don’t officially. No one will say, “We won’t take a 38‑year‑old with two kids.” But they absolutely think through the practicalities: training length, stamina, financial pressure, partner burnout. You neutralize that concern by showing you’ve already gamed out the next decade—childcare plans, financial runway, support system. When older applicants speak concretely about those realities, they suddenly look less risky than a 22‑year‑old who’s never paid a bill.What’s the biggest mistake high‑earning career‑changers make on their applications?

They oversell and under‑prove. Long paragraphs about “meaning,” “impact,” and “purpose,” with almost no concrete evidence that they’ve lived in clinical spaces over time. The second‑biggest mistake is trashing their old career like it was pointless. That reads as unstable. The strongest applications respect the old path, show precisely why it was misaligned with their deeper motivations, and connect that experience to medicine without pretending it was all a waste.

If you strip this down to essentials:

- They’re not just asking, “Are you smart enough?” They’re asking, “Will you still be here in 10 years, sane, functional, and useful?”

- The more you show a long, tested, financially and emotionally realistic pivot, the shorter the behind‑the‑scenes debate about you becomes—and that’s exactly what you want.