The obsession with a “killer” Step 3 score is massively overblown. For most people, grinding for a 250+ on Step 3 is a terrible use of limited time and energy.

Let’s walk through what the data actually supports and where the high-score cult is just anxiety dressed up as strategy.

What Step 3 Actually Does (Not What People Say It Does)

Step 3 is not Step 1 circa 2015. It’s not the gatekeeper of your future. It’s a box to check and, for a minority of residents, a mild lever.

Here’s the simplified reality of Step 3’s role:

- Licensing requirement: You need to pass it for full medical licensure in the U.S. That’s non‑negotiable.

- For most competitive decisions (residency match, fellowship): Step 3 is either irrelevant or a minor tiebreaker.

- The test is designed so residents can pass while working full time. That alone should hint at how the system thinks about it.

Passing is important. Scoring sky‑high is rarely transformative.

Let me show you where a Step 3 score does still matter (and how much).

| Context | Importance of High Score |

|---|---|

| Getting a residency (MD/DO) | Very low to none |

| Getting a residency (many IMGs) | Low–moderate (selectively) |

| Fellowship in competitive fields | Mild tiebreaker sometimes |

| Remediation after weak Step 1/2 | Helpful but not a magic fix |

| State licensure | Pass/fail only |

Now, let’s layer in some actual numbers and tradeoffs.

The Numbers: Pass Rates, Time, and Diminishing Returns

First, the baseline: Step 3 is not a “killer” exam in terms of pass rates.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| US MD | 97 |

| US DO | 94 |

| IMG | 86 |

US MD and DO grads overwhelmingly pass on the first attempt. IMGs have lower pass rates, but still, most pass. So the core rational question is:

How much extra time should you spend to move from “likely pass” to “high score”?

Here’s the rough tradeoff I see repeatedly in residents’ real lives:

| Total Focused Study Time | Common Score Outcome |

|---|---|

| 40–60 hours | 210–220+ (pass comfortably) |

| 80–100 hours | 220–235 |

| 120–160+ hours | 235–250+ |

Not perfect, but this pattern is familiar:

- The first 40–60 hours massively reduce failure risk.

- Each additional 20–40 hours buys you smaller and smaller score gains.

- Pushing up into the “flex” range (240+) often costs you an extra 60–80 hours you absolutely do not have lying around in residency.

Now, ask the question most people conveniently avoid: What would those 60–80 extra hours have been used for instead?

- Sleep and not wrecking your performance on the wards

- Building relationships with attendings who will actually write your letters

- Protected time for research or that one QI project your PD cares about

- Fellowship-focused reading (cardiology, heme/onc, GI, etc.)

You are not choosing between “high Step 3 score” and “doing nothing.” You are choosing between “high Step 3 score” and “being more effective and visible where it actually counts.”

Myth #1: “You Need a High Step 3 Score for a Good Fellowship”

This one is sticky because it sounds plausible and it’s occasionally true. But mostly, it’s lazy thinking.

Look at any reputable program’s fellowship match data. Big-name IM, peds, and surgery residencies routinely match fellows into cardiology, GI, heme/onc, MFM, etc. You’ll absolutely find people in those programs with:

- Solid but unspectacular Step 1/2

- Completely average Step 3 (220s–230s)

- Stellar letters, strong in‑training exam (ITE) scores, visible research work

What PDs actually say (in meetings, not marketing brochures):

- “I care much more about what their attendings say in the letters.”

- “Show me their ITE trajectory. Are they learning in residency?”

- “Are they the person everyone wants on service?”

Step 3 in fellowship selection:

- If they see a fail → they notice. You will need an explanation.

- If they see a weak Step 1/2 and a strong Step 3 → they may view that as academic recovery.

- If they see 231 vs 242 on Step 3 → nobody cares.

For competitive IM subspecialties, what really drives outcomes:

- Strong IM residency program and reputation

- Research in the target field (posters, pubs, or at least involvement)

- Enthusiastic, detailed letters from people fellowship PDs know

- Good ITE and clinical performance

Step 3 is at best a third- or fourth-tier variable.

Myth #2: “A High Step 3 Score Will ‘Fix’ My Low Step 1/2”

This is the “redemption arc” fantasy. I see it a lot with residents who matched into a mid- or lower-tier program and want to “prove” themselves.

Reality: Step 3 is a modest signal, and fellowship directors know that:

- It’s taken later, after you’ve already been through medical school and often some residency.

- It’s less discriminating at the top end—tons of people cluster in the 220–240 band.

- Preparation quality is heavily constrained by residency demands, so it’s not the same clean metric as Step 2.

What a strong Step 3 can do for a historically weaker test taker:

- Signal upward trajectory: “They struggled early, but they’re clearly improving.”

- Reduce concern that you’re at risk of failing boards going forward.

- Give your PD something positive to say in the letter: “They’ve really stepped up academically.”

But you are not rewriting your entire academic record with this one test. A 246 on Step 3 does not erase a 215 Step 1 and mediocre clinical comments.

It helps. It does not transform.

When a High Step 3 Might Be Worth Extra Time

There are a few real scenarios where aiming above “just pass” is rational. Notice I said above “just pass,” not “destroy the curve.”

1. You’re an IMG still trying to move up the ladder

If you:

- Matched into a less-known or community-heavy program, and

- Are aiming for a very competitive fellowship or a jump to an academic job

Then a legitimately strong Step 3 (say 235–245) can add weight to:

- Solid ITE performance

- Strong clinical evals and letters

- Active research or scholarly work

But even here, the main outcomes come from what you do in residency, not Step 3. Step 3 is a supporting actor, not the lead.

2. You had a prior USMLE failure

If you’ve failed Step 1 or Step 2 in the past, a clean, solid Step 3 performance matters more.

In this case, I’d argue:

- You should not aim for just barely passing.

- You should invest to land clearly above the pass line, ideally into “respectable” territory (220s+).

Because what fellowship PDs and licensing boards want to see is:

- No pattern of repeated failures

- Evidence that whatever caused the original failure has been fixed

But notice the target: solid and clearly passing. Not “heroic 250.”

3. You’re in a shaky program or at risk academically

If your program is under scrutiny, or you’re borderline on evaluations or ITEs, Step 3 becomes another data point in your favor.

Even then, the move is:

- Make sure you don’t fail.

- Aim for a result that PDs can point to and say, “See? They’re fine.”

That’s rarely the same as “live like a hermit and sacrifice 4 months to chase a top decile score.”

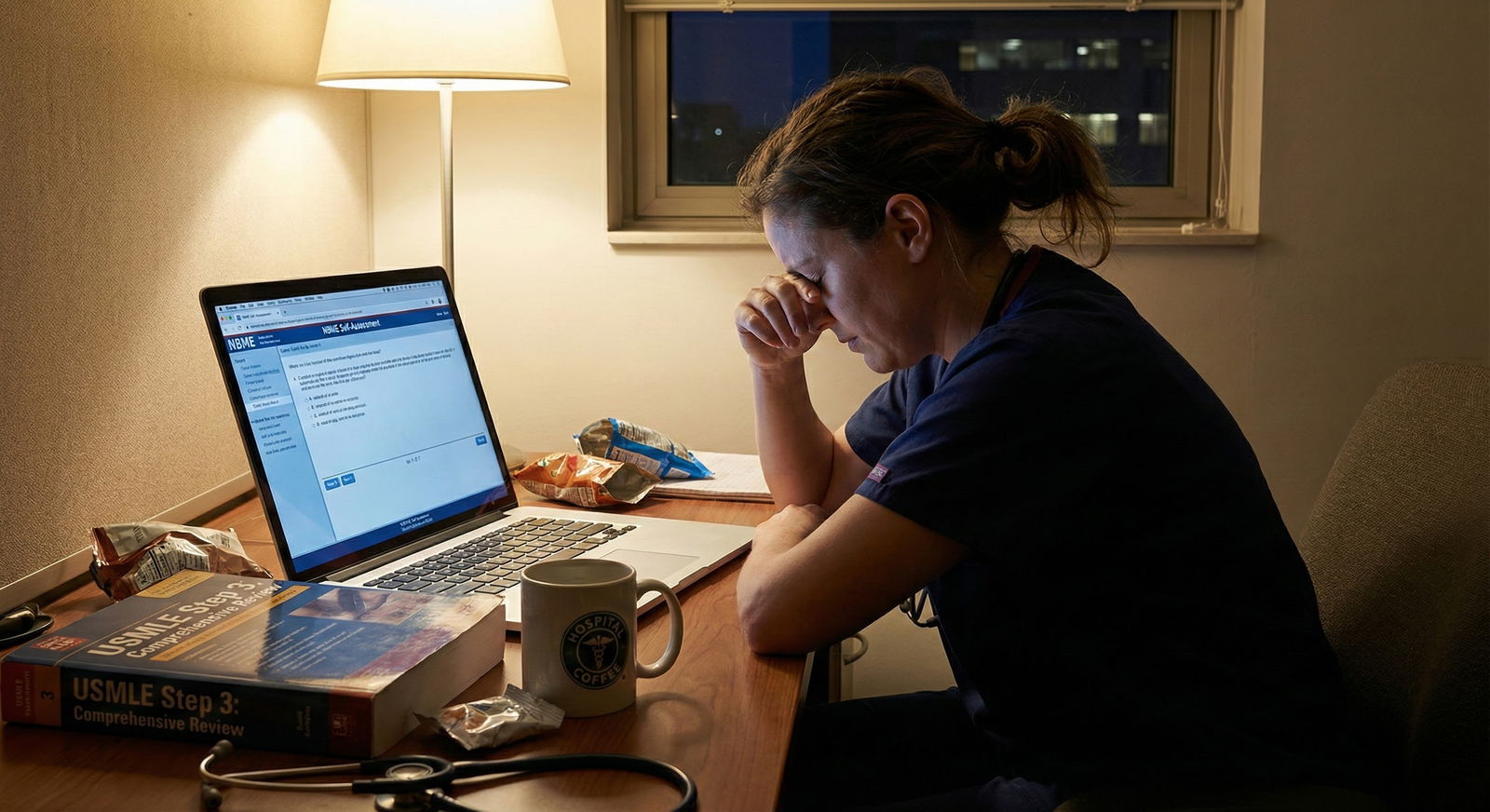

Where the Extra Hours on Step 3 Actually Hurt You

This is the part almost nobody talks about because it forces you to admit you can’t do everything.

Those extra 60–80 hours you spend pushing from “safe pass” to “brag-worthy” Step 3 score usually come from one of these buckets:

- Sleep: You show up to wards foggy, slow, irritable. Your clinical performance drops just when you’re trying to impress people.

- Clinical reading: Instead of skimming UpToDate or primary literature relevant to your patients, you’re doing yet another random question block about outpatient derm rashes.

- Relationships: You’re skipping social events with co-residents, dodging informal time with attendings, or saying no to opportunities (“Want to work on this QI project?”) because you’re “in dedicated.”

- Research: That one abstract or paper that could actually move your fellowship app? It gets delayed six months or dies entirely.

Here’s a blunt hierarchy most residents don’t want to write down but should:

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Strong letters & relationships | 95 |

| High-quality research output | 85 |

| Residency program reputation & performance | 80 |

| Step 3: pass cleanly | 60 |

| Step 3: push score from solid to high | 15 |

Is that exact numeric? No. But directionally, it’s how PDs actually behave.

Step 3: pass cleanly — important.

Step 3: chase marginal gains for prestige — marginal.

How Much Study Is “Enough” for Most People?

Here’s the part you probably came for.

Assuming you’re a typical PGY-1 or PGY-2 in IM, peds, FM, EM, etc., with no prior board failures:

Reasonable targets:

- Total study time: 40–80 hours

- Resources: One qbank (UWorld or Amboss), plus CCS practice cases

- Goal: Score comfortably above pass (say 210–225+), avoid any hint of struggle

Rough breakdown:

- 30–50 hours of random/timed MCQ blocks + review

- 10–20 hours on CCS (practice using the interface and core management patterns)

What you don’t need:

- Elaborate textbook deep dives

- Anki empires

- A multi-month “dedicated” period

You’re better off:

- Doing consistent, focused blocks on lighter rotations

- Taking the exam on a reasonable timeline (often PGY-1 late year or early PGY-2) so you’re not dragging it like an anchor

If you have risk factors (prior failure, low Step 2, test anxiety, IMG with shaky knowledge base), bump that to maybe 80–120 focused hours. But still with the main goal: pass strongly, not “Step 1 nostalgia tour.”

The Hidden Psychological Trap: Step Score Identity

One more uncomfortable truth.

A lot of Step 3 overstudying isn’t strategic. It’s emotional. It’s identity maintenance.

Med students and residents who were “the smart one” often hang their self-worth on test scores. Step 3 becomes the last big exam where you can chase that feeling of superiority. So they tell themselves it’s for fellowship or their “career,” but the actual driver is:

“I want to prove to myself I’m still that person.”

I’ve seen residents:

- Sacrifice months of bandwidth to maintain an internal narrative no program director cares about

- Melt down because they “only” scored in the 220s on Step 3 despite being exhausted on service

- Ignore low‑hanging fruit (research, networking, teaching opportunities) because they’re still chasing standardized test validation

If you recognize yourself in that description, you need a different plan, not a different qbank.

So, Is a High Step 3 Score Worth the Extra Study Time?

Usually? No.

Let me distill it.

- For the vast majority of residents, the smart move is to study enough to pass comfortably and then stop. Roughly 40–80 focused hours, a solid qbank, and CCS practice will get most US grads there.

- A truly high Step 3 score is strategically worthwhile only in specific scenarios: IMG trying to move up, prior board failure, or very competitive fellowship from a weaker program. Even then, it’s a supporting detail, not the engine of your application.

- The opportunity cost of chasing a vanity Step 3 score is real: worse clinical performance, weaker relationships, missed research. Those three matter far more to your career than the difference between a 222 and a 242 on a licensing exam almost nobody deeply cares about.

Treat Step 3 like what it really is: a licensing hurdle and a minor signal, not the final referendum on your worth as a physician.