The mythology around “you need a first‑author NEJM paper to match competitive specialties” is statistically false. The data show something sharper and more useful: you need to hit realistic, specialty‑specific research productivity thresholds—and then use that work strategically.

I will walk through quantitative research benchmarks for the 5 most competitive specialties based on recent NRMP and AAMC data trends:

I am not guessing. I am leaning on the pattern that shows up every year: applicants who match these specialties sit in the extreme right tail of research involvement metrics.

1. The Data Landscape: What “Research Productivity” Actually Means

Before we go specialty by specialty, you need to understand what the numbers are—and what they are not.

The NRMP and AAMC historically report a broad bucket: “abstracts, presentations, and publications.” That bucket is noisy. A single poster at a local research day and a first‑author JAMA paper each count as “1.” Ridiculous, but that is the system.

So when you see “average matched applicant has 18 abstracts/presentations/publications,” do not imagine 18 PubMed‑indexed manuscripts. The reality usually looks closer to:

- A few serious manuscripts (often 1–4, sometimes more for MD/PhD or research‑heavy)

- Several conference abstracts or posters

- Some case reports / small series

- A handful of student research day or institutional presentations

To make this concrete, I will translate those “total items” into realistic benchmarks:

low, median, and high research productivity bands for matched applicants.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Derm | 22 |

| Plastics | 24 |

| Ortho | 16 |

| ENT | 18 |

| Neurosurg | 20 |

Think of those values as a rough proxy for “average total research items for matched US MD applicants” (public + posters + abstracts), acknowledging minor year‑to‑year variation.

You are not aiming to hit exact numbers. You are aiming to compete with the distribution.

2. Dermatology: The Research Arms Race

Dermatology is where research inflation is most obvious. The data show 2 things pretty consistently:

- Match rate is relatively low despite very high applicant quality.

- Research volume for matched applicants sits at the top of all specialties.

A realistic, modern snapshot for successful derm applicants:

- Total abstracts/presentations/publications: commonly 18–25+

- First‑author PubMed‑indexed papers: often 2–4

- Dermatology‑focused projects: at least 1–2, frequently more

Here is how I would translate this into productivity bands.

| Band | Total items | Peer‑reviewed papers | Derm‑focused projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | 12–18 | 1–2 | ≥1 |

| Strong | 18–30 | 2–4 | 2–3 |

| Exceptional | 30+ | 4+ | 3+ |

If you are at a “Competitive” level (say 15 total items, 2 papers, 1 derm project) but not Strong/Exceptional, you will need compensatory strengths:

- Stellar Step 2 CK (think well above the national mean)

- Strong home dermatology department or away rotation performance

- Convincing letters from dermatology faculty who actually know you

I have seen people match derm with single‑digit numbers when they are at powerhouse institutions, have sky‑high scores, and have a department going to bat for them. Outlier cases. Do not plan your strategy around those.

If you are below 10 items total and no derm‑specific work, you are statistically outgunned for the median derm program, unless you are adding a dedicated research year.

3. Plastic Surgery (Integrated): Early and Focused

Integrated plastics behaves like derm but with an even stronger preference for surgical and plastics‑related output.

Key patterns:

- Many successful applicants start research in M1 or even undergrad.

- Research years are common, especially among those targeting top‑tier programs.

- Case reports and technical notes count, but high‑yield groups expect multi‑project involvement.

Realistic ranges:

- Total abstracts/presentations/publications (matched): ~20–25 often reported

- First‑author surgical/pliastics papers: 2–4+ for many successful candidates

- Plastics‑focused output: 2+ projects is increasingly common

| Band | Total items | Peer‑reviewed papers | Plastics/surgical focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | 10–16 | 1–2 | ≥1 plastics/surg |

| Strong | 17–28 | 2–4 | 2–3 plastics |

| Exceptional | 29+ | 4+ | 3+ plastics |

If you are aiming for integrated plastics with less than ~10 total items and no plastics‑specific work, the probability curve is brutally steep against you, unless:

- You pivot to a research year in plastics

- Or you re‑target a slightly less research‑hungry surgical field

Programs are not just counting volume. They are screening for signal:

- OR‑adjacent research (wound healing, reconstruction outcomes, microsurgery, craniofacial, hand)

- Work with known plastics faculty who can pick up the phone for you

- Evidence that you can see a project from IRB to manuscript submission

The numbers matter. The type of those numbers matters more.

4. Orthopaedic Surgery: High Volume, Moderate Depth

Orthopaedics has quietly become one of the highest research-output specialties among applicants. The averages look high mainly because many ortho applicants crank out a large number of retrospective studies, case series, and conference abstracts.

Signature pattern:

- A lot of applicants show double‑digit totals.

- Many items are institution or specialty meeting abstracts/posters.

- There is a big premium on ortho‑focused work over generic bench research.

Reasonable bands:

| Band | Total items | Peer‑reviewed papers | Ortho‑specific projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | 8–12 | 1–2 | ≥1 |

| Strong | 13–20 | 2–3 | 2+ |

| Exceptional | 21+ | 3+ | 3+ |

You can absolutely match ortho with 8–12 total items if:

- At least one is a legit ortho paper or a high‑quality abstract

- You have strong Step 2 CK and class performance

- You perform well on away rotations and get strong letters

I have watched applicants with 25+ items but almost none ortho‑related struggle more than those with 10 items tightly focused in orthopaedics. Volume helps, but specialty‑specific alignment is what moves you up a program’s rank list.

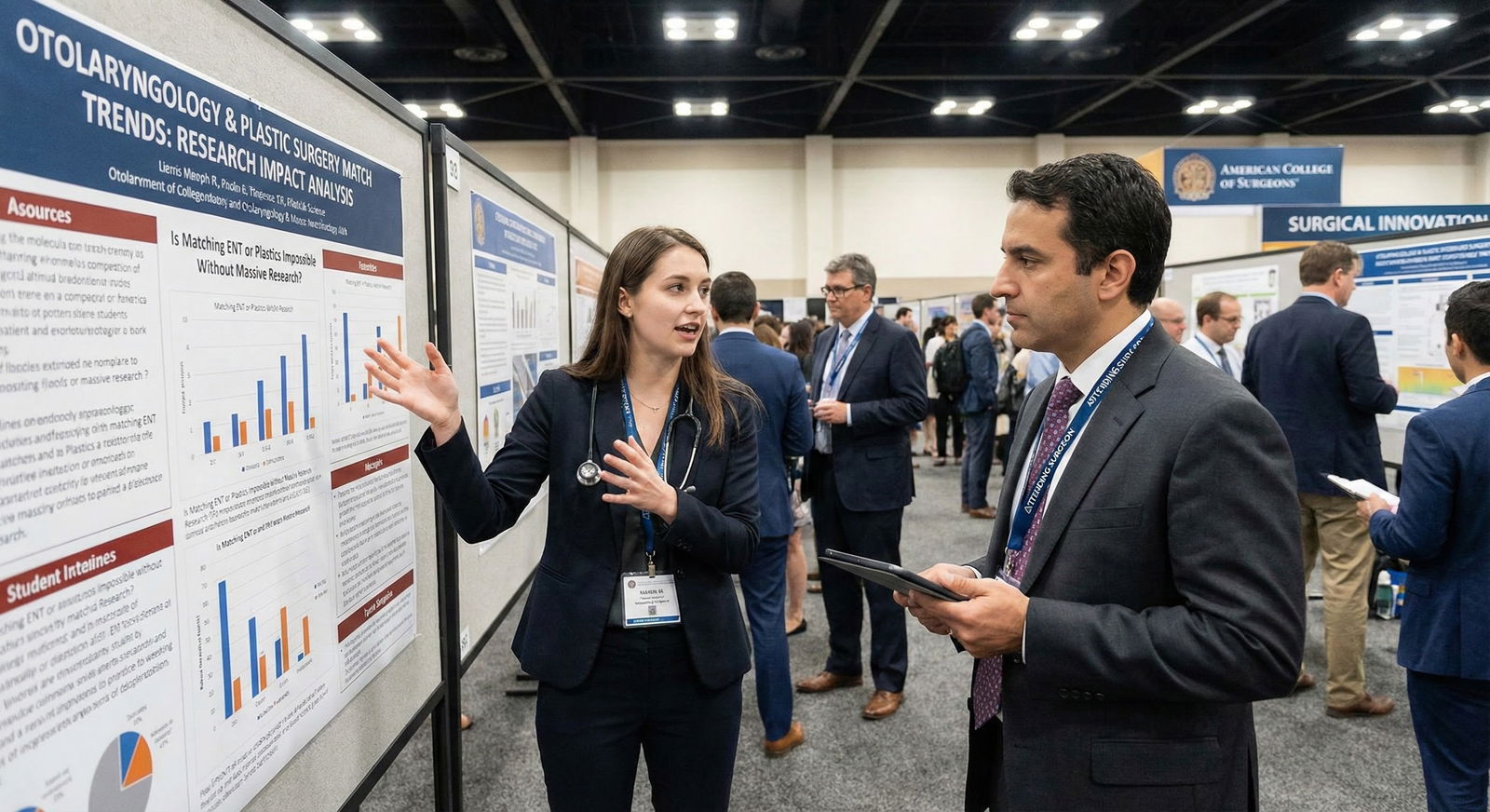

5. Otolaryngology (ENT): Research as a Differentiator

ENT sits in a strange middle ground—fewer positions nationwide, high applicant quality, and a strong research culture, especially at academic programs.

Pattern from recent cycles:

- ENT applicants who match often show mid‑to‑high double‑digit total items.

- ENT‑specific work is common; faculty know the tight network of frequent authors.

- MD/PhDs and research‑track types skew the mean upward.

Approximate ranges:

- Average total items in the teens to low 20s for matched US MD applicants

- 2–3+ peer‑reviewed papers is common at academic‑heavy match lists

| Band | Total items | Peer‑reviewed papers | ENT‑specific projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | 8–14 | 1–2 | ≥1 |

| Strong | 15–22 | 2–3 | 2+ |

| Exceptional | 23+ | 3+ | 3+ |

The big difference in ENT vs derm/plastics: you can still compete with slightly lower volume if you have:

- Strong ENT letters (ideally including the program director or chair at your home/away site)

- Obvious clinical fit and reliability on rotations

- A smaller number of high‑impact ENT projects (e.g., multi‑center or high‑impact journal)

But if you show up with 0 ENT‑related projects and a handful of random preclinical lab work, you are behind the statistical pack.

| Category | Value |

|---|---|

| Derm | 18 |

| Plastics | 16 |

| Ortho | 12 |

| ENT | 14 |

| Neurosurg | 15 |

(Values represent the upper limit of the “Competitive” band for total research items.)

6. Neurosurgery: Depth, Not Just Volume

Neurosurgery is academically intense, but the culture is a bit different from derm and plastics. The field selectively rewards:

- Sustained involvement in one or two neurosurgical research groups

- Longitudinal outcomes work, clinical series, or basic science with clear neurosurgical relevance

- Technical case reports and operative technique papers

Expect to see:

- Many matched applicants with 15–25+ total items

- 2–5+ peer‑reviewed papers

- Multiple neurosurgery‑specific projects, sometimes starting early in M1 or before

| Band | Total items | Peer‑reviewed papers | Neurosurg‑specific projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | 10–15 | 1–2 | ≥1 |

| Strong | 16–25 | 2–4 | 2–3 |

| Exceptional | 26+ | 4+ | 3+ |

The difference in neurosurgery is that programs care a lot about trajectory. PDs are used to seeing applicants who have been in a single lab for 2–3 years, accumulating multiple outputs with the same senior authors.

If your CV shows:

- 1–2 neurosurgical projects sustained over multiple years

- 2–3 papers, some as first author

- Multiple national meeting presentations (AANS, CNS, or major subspecialty meetings)

then you are playing in the same league as many strong applicants, even if your total item count is lower than the derm/plastics headline numbers.

7. How Programs Actually Interpret These Numbers

The dangerous misconception is that programs rank applicants by simple quantity. That is lazy thinking. Strong programs subconsciously use a weighted model:

Specialty alignment

- A single high‑quality, specialty‑specific paper is more valuable than five generic preclinical posters.

Role and authorship

- First‑author papers and oral presentations suggest you drove the project.

- Being the 8th author on a massive dataset suggests you were “on the email thread.”

Continuity

- 3 years with one mentor and a coherent story of your research arc > 1 year splashing across 5 labs.

Signal in letters

- “This student independently designed the methodology and wrote the first draft” lands differently than “This student helped collect data.”

If you want a crude formula:

Real Research Score ≈

(2 × first‑author specialty papers)

- (1 × co‑authored specialty papers)

- (0.5 × specialty abstracts/posters)

- (0.25 × non‑specialty work)

Nobody is literally doing this math, but PD brains do something close to it when they scan your ERAS.

8. Strategy: Hitting Your Target Band Without Wasting Time

You do not need to chase arbitrary double‑digit totals if you are smart about project selection.

Here is the streamlined path I have seen work repeatedly for competitive‑specialty applicants:

Lock in one primary mentor in your target specialty by early M2 at the latest.

Stack your projects under that mentor or within that research group. Examples:

- 1 retrospective outcomes study (longer timeline, higher yield)

- 1–2 case reports / technical notes (shorter timeline, lower yield but easier)

- 1 educational or QI project with publishable potential

Add 1 project with another faculty if there is a clear angle:

- Multi‑institutional collaboration

- Distinct subspecialty (e.g., peds derm vs procedural derm)

Translate every serious project into at least one presentation or poster.

If you do this consistently for 18–24 months, you land in the Strong band for most of these specialties without needing to play the “inflate my CV with fluff” game.

| Period | Event |

|---|---|

| Preclinical - M1 Spring | Join specialty lab |

| Preclinical - M2 Fall | Submit first abstract |

| Clinical - M3 Spring | Submit first manuscript |

| Clinical - M3 Summer | Present at national meeting |

| Application Year - M4 Early | 2+ papers accepted or in review |

| Application Year - ERAS Submission | Update CV with all outputs |

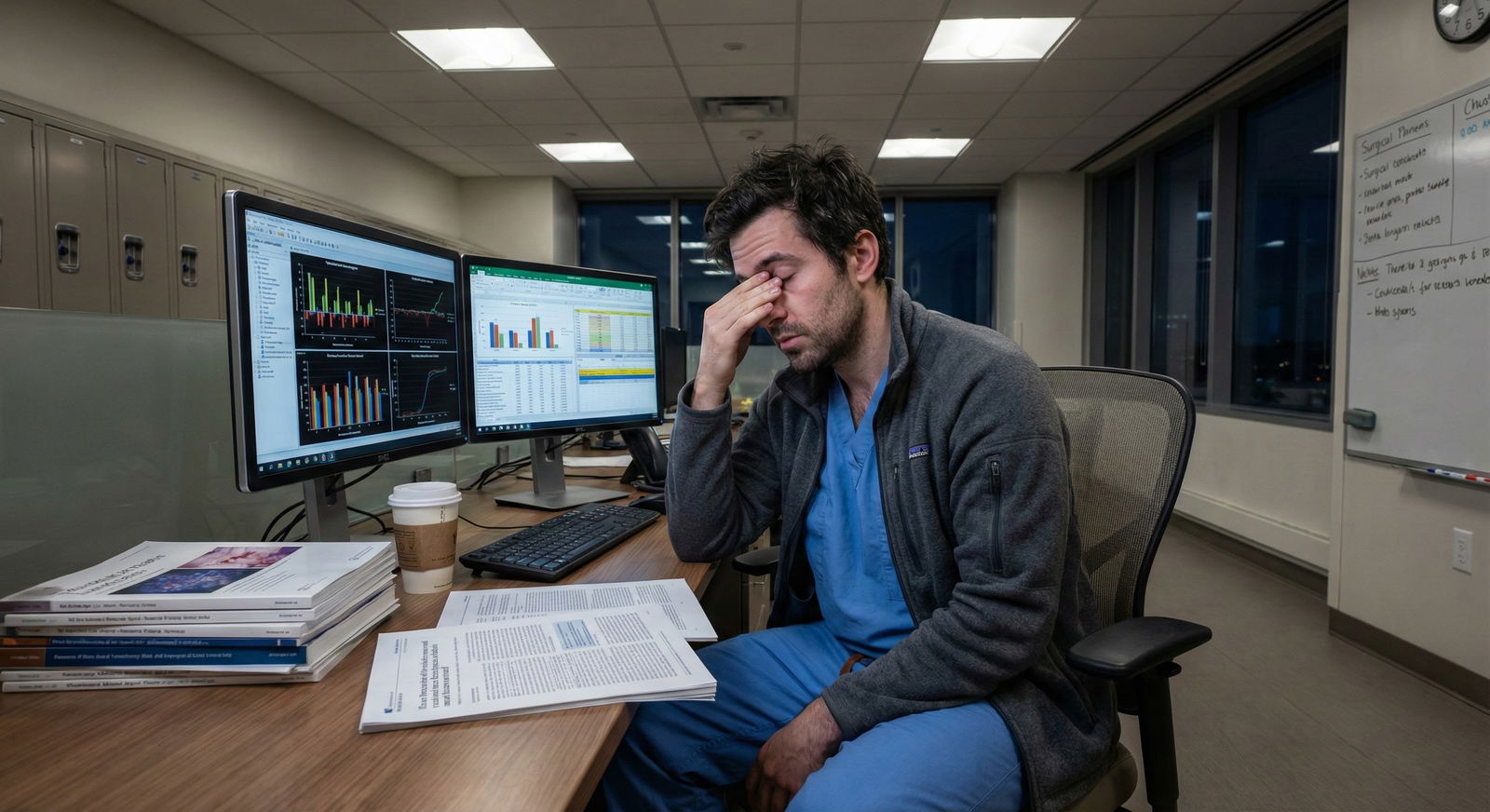

9. When You Are Below the Benchmarks

Here is the harsh but honest part. If your numbers are significantly below the Competitive band for your target specialty, you have 3 realistic options:

Add a dedicated research year

- Especially common in derm, plastics, neurosurgery.

- Goal: move from “low” to “Strong” or “Exceptional” band in 12–18 months.

- Works best if done within an established, publishing lab.

Refocus your specialty target

- Some fields still care deeply about research, but the median bar is lower.

- Example: general surgery vs plastics; internal medicine vs derm.

Accept a more risk‑tolerant strategy

- Apply anyway with fewer programs and hope: not intelligent.

- If you cannot or will not add a research year, you must compensate massively in Step 2 CK, clinical performance, away rotations, and letters.

The data are unforgiving. If your specialty has a median of ~20 total items, and you have 3 with none specialty‑specific, the prior probability of matching at a random program is simply low.

10. Putting It All Together: Quick Benchmark Snapshot

Here is a simple cross‑specialty comparison, focusing on a realistic “Strong” target band for a US MD applicant who wants to feel competitive at a broad set of programs.

| Specialty | Total items (Strong band) | Peer‑reviewed papers | Specialty‑specific projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dermatology | 18–30 | 2–4 | 2–3 |

| Plastics (Int) | 17–28 | 2–4 | 2–3 |

| Orthopaedics | 13–20 | 2–3 | 2+ |

| ENT | 15–22 | 2–3 | 2+ |

| Neurosurgery | 16–25 | 2–4 | 2–3 |

You do not need to land at the top of every range. But if you are dramatically below these bands with no compensatory features, you are relying on outlier luck.

FAQ (Exactly 5 Questions)

1. Do I really need 20+ research items to match a competitive specialty?

No. You need to be competitive relative to other applicants. In derm and plastics, that often looks like mid‑to‑high teens at minimum, but not everyone with 20+ items matches and not everyone below 10 fails. The decisive variables are specialty alignment, depth of involvement, and letters. A focused 10–12 items with 2–3 solid papers in your field can beat a scattered 25.

2. How much does non‑specialty research help (e.g., basic science in a different field)?

Non‑specialty research helps mainly by showing you can complete projects: design, data, manuscript. It boosts your floor but has limited ceiling effect. For competitive specialties, think of non‑specialty work as a base layer; you still want at least 1–2 substantive projects inside the specialty to signal genuine interest and fit.

3. Are case reports and small series actually valuable?

Yes, but as supporting players. Case reports are fast and can move the needle on your total item count and give you first‑author experience. However, programs do not view ten case reports as equivalent to one strong cohort study. Ideal pattern: a few case reports early to learn the process, then transition to higher‑impact retrospective or prospective work.

4. Does a research year “fix” a weak CV for these specialties?

A research year is a multiplier, not a magic reset. If you embed in a productive lab with a strong mentor, you can realistically add 10–20+ items (posters, abstracts, papers) and move from weak to Strong/Exceptional bands. If you spend a year on a single low‑yield project with no outputs by ERAS submission, the year does not rescue your application. Choice of lab and mentor is everything.

5. How late is too late to start research for a competitive specialty?

Starting after Step 2 CK is usually too late to meaningfully alter the current application cycle. Starting in late M3 can still produce abstracts and possibly a paper if the projects are well chosen, but you are unlikely to hit high‑end benchmarks without a research year. The highest‑yield window for building a competitive portfolio is M1 through early M3, with M2 being the sweet spot for most students.

You now have a realistic map of what the research landscape looks like for the top 5 competitive specialties. The next step is not staring at the numbers—it is choosing one mentor, one lab, and the first two projects that will start pushing your CV into the right band. Once that machinery is running, we can talk about how to convert those projects into the kind of letters and interview performance that actually seal the match. But that is a story for another day.